Whenever I lobby a Congressional, a legislative office, or speak directly to an elected official to urge them to pass climate legislation, I feel like I am keeping alive the spirit of one individual who made a deep impact on me: William Gladstone Steel. He is also referred to as, ‘Will Steel.’

I discovered Will Steel when I worked as a park ranger at Crater Lake National Park from 1992-2017. He was the subject of my ranger lodge talk from 2006-2017. Will Steel lived from 1854 to 1934. I doubt he ever heard about climate change. However, he had a passion for conservation and the environment since he is known to this day as ‘The Father of Crater Lake National Park.’

Steel’s tireless tenacity to make a difference impacted me. In every ranger talk I gave, I hoped his story would inspire my audience that each one of them could make a positive impact in the world. If you are reading this blog, I hope his story and mine will influence you.

This blog is my story how I discovered Will Steel and my ranger talk how I interpreted his life.

My Story of Discovering Crater Lake

I graduated from William Jewell College on Sunday afternoon May 17, 1992, with a degree in Business Administration. I enjoyed my business classes in college, but I decided to never work in an office cubicle. Just hours after the graduation ceremony, I boarded an Amtrak Train heading from Kansas City, Missouri to Los Angeles, California. The fantastic western scenery from the train window helped me close the chapter on my college years and my entire life at that point of living in Missouri. I was eager for my new life adventure in the Pacific Northwest.

From LA, I caught another train called “The Coast Starlight,” with fabulous scenery of California from the train windows took me to my destination of Klamath Falls, Oregon. The final morning of this trip train started fantastic with a breath-taking view of the 14,000-foot Mt. Shasta as the train curved around the huge mountain.

An employee of the Crater Lake Lodge Company named Kevin picked me up at the train station on May 20, 1992. It took over an hour to drive from the Klamath Falls train station to Crater Lake. Kevin and I chatted a lot during the drive. I was so eager to see Crater Lake. I kept pointing at the scenery and asking him: ‘Is Crater Lake behind that mountain?’

‘No,’ he kept responding. ‘Don’t worry! You will eventually see it.’

When I arrived at the Crater Lake Rim Village. The scenery did not disappoint. Crater Lake was one of the most spectacular sights I saw in my life. The lake was 6 miles across at its widest point with this deep cobalt blue color. The rim mountains that surrounded it were decorated with snow, looking like an amazing cake decoration with the white icing on top. The pine trees where so tall, unlike the much smaller deciduous or leaf producing trees in my home state of Missouri. It was so quiet standing on the rim admiring the lake, except for the very light whistle of the wind and an occasional airplane flying overhead.

In a sense, my life changed forever seeing Crater Lake for the first time. I found my new home. I never did like the heat, humidity, and dearth of snowcapped mountains in Missouri. May is still a winter month at Crater Lake and I would see it snow falling within the next day or two. The crisp colder temperatures felt like natural air conditioning to me, compared to the very hot and muggy summer temperatures in Missouri. I could not wait to discover hiking on the trails in the park and wandering to different locations to admire the beauty of Crater Lake National Park.

I did not think much about Will Steel in my early years working at Crater Lake. I knew he was the park founder, but that was all. However, my first impression was similar than when William Gladstone Steel saw it for the first time on August 15, 1885. One year afterwards, he wrote:

“Crater Lake is one of the grandest points of interest on earth. Here all the ingenuity of nature seems to have been exerted to the fullest capacity, to build one grand, awe-inspiring temple, within which to live and from which to gaze up on the surrounding world and say: ‘Here would I dwell and live forever. Here would I make my home from choice; the universe is my kingdom, and this is my throne.’”

A key point of that quote is ‘the universe is my kingdom.’ Crater Lake does not just enchant during the daytime. Except for the distant cities of Eugene and Klamath Falls, Crater Lake has minimal light pollution. Thus, the stars really shine on a moonless light like countless jewels, especially clustered around the Milky Way Galaxy trail in the middle of the sky. I never saw so many stars like that before growing up under the light pollution of the St. Louis metro area and going to college in the Kansas City metro area. With the dark skies and endless stars, Crater Lake is an ideal place to contemplate one’s place in the universe.

Crater Lake as a place of romance and wonder

My first Crater Lake summer was magical. I enjoyed my job working as a stock clerk at the huge Crater Lake Gift Store at Rim Village. I found friends to go hiking with me to help me explore every scenic trail in the park that summer. If no one was available, I happily hiked on my own.

Crater Lake was a very romantic place that the concession staff found ways to couple off, date, and sneak into each other’s beds in the co-ed staff dormitory. The romance of the location caught up with me when I found my first girlfriend Sheila that summer. Both of us explored intimacy with each of us losing our virginity that fall as the outside temperatures declined with winter fast approaching in October. Crater Lake’ enchanting power and later working in Everglades National Park together kept our relationship going for eight years. We eventually drifted apart as our interests diverged and compatibility waned. Others may say Paris, France is the most romantic place in the world. Personally, the romantic beauty of Crater Lake is like nothing other.

The romance, the enjoyment of working and living in the park, the opportunities for fabulous hiking right outside my door, the spectacular beauty, and the friends I made kept bringing me back to Crater Lake during the summers for the next 25 years. Like Will Steel, I could not get enough of that park. I found different seasonal summer jobs to keep me rooted there.

In the summers of 1993 and 1994, I worked as a gift store lead clerk. In 1995, the General Manager of the Crater Lake Company asked me to work as the night auditor at the newly rehabilitated Crater Lake Lodge, which reopened that year. I soon discovered working all night and sleeping through the daytime splendor of Crater Lake was not my cup of tea. In 1996, the National Park Service (NPS) hired me to be an entrance station fee collection ranger at Crater Lake. I enjoyed this job, except for the occasional angry visitors who were upset when I charged them the then $5 entrance fee that to enter Crater Lake National Park.

I worked this ranger job the following summer in 1997. Around that time, NPS then changed the job title to Visitor Use Assistant (VUA). I didn’t care what they called me. I just loved wearing the ranger uniform, as well as living and working at Crater Lake. I did not become financially rich working at Crater Lake, but my life experience seemed so incredibly rich working there.

Rediscovering Crater Lake and becoming an interpretations ranger

From 1998 to 2002, I found a year-round position working as a naturalist guide on the boat tours at the Flamingo Outpost in Everglades National Park. I enjoyed the convenience of living in one location all year, as opposed to only working from May to October at Crater Lake. The Everglades wildlife was magnificent with the alligators, crocodiles, dolphins, manatees, and wide variety of colorful birds. I loved narrating about the history, ecology, and pointing out the wildlife to the park visitors and birdwatching on my own in my free time. However, by the spring of 2002, I was burned out of working my job in Flamingo. Crater Lake was calling me back home.

Renowned American naturalist John Muir once wrote: “The mountains are calling and I must go.”

I totally understood that sediment. On February 22, 2002, I bought a brand-new green Honda Civic, which I still drive to this day. I no longer felt stranded to the Everglades without a car. It was time to leave and return to the place I loved so deeply: Crater Lake National Park. Like the summers of 1996-97, I worked as a VUA ranger at the entrance stations during the summer of 2002. It felt like such a blessing to wear the ranger uniform again. Sheila and I ended our dating relationship in Flamingo in 2000. It took years for me to rediscover myself. Crater Lake was a place of rejuvenation and healing for me to create a new life for myself as a single person.

In the summers of 2002-2005, I worked this VUA ranger position at Crater Lake. By 2006, I wanted a new job at Crater Lake. The Crater Lake naturalist rangers, or interpretation rangers as the NPS called them, seemed to really enjoy their jobs at Crater Lake. They narrated the boat tours, lodge talks, guided hikes, and led evening campfire programs for the park visitors. I hung out with them in my free time. I wanted to be one of them. I was very excited receiving the phone call in early May that I was hired as a Crater Lake interpretation ranger for the summer of 2006.

In June 2006, the Crater Lake Interpretation staff had three weeks of training before we gave our ranger talks during the summer. Time was short to create an original lodge talk.

Creating a ranger lodge talk around William Gladstone Steel

For some reason, the park founder, William Gladstone Steel, intrigued me. His life story, especially how it related to the history of how Crater Lake became a national park, seemed like a very rich story to interpret for park visitors. Like any historical person, his life story included bravery to overcome steep obstacles. At that same time, his story contained some humor how he would step on toes and push other people around to get what he wanted. He made enemies how he treated people. Steel’s enemies were not always the bad guys, sometimes he was. He was not always an angel. Quite frankly, at times, he could be a jerk.

The lead naturalist Dave Grimes and I both thought Will Steel could be perfect subject for a lodge talk because he was relatable. He was a flawed human being that succeeded because of and despite his flaws. He was like a family member in that you could love and admire, but other days you would want to scream and even disown them. My talk would not be a ‘living history talk’ where I would pretend that I was Will Steel, wear a costume, and portray him to an audience like an actor would. However, this would be the type of character that a stage or screen actor would kill to play since he is such a complex and dynamic character.

When I later described how I interpreted Will Steel in my lodge talk, I would tell anyone that talking about Steel was similar to giving a ranger talk on the late President Richard Nixon. I would say that ‘Like Nixon, there was some good things and some not so good things.’

Ironically, my mentor in the national parks, Ranger Steve Robinson, who I knew from 1993 from working in both Crater Lake and the Everglades thought that Steel was a charlatan and a greedy fraud. He could not stand him and thought he had few redeemable qualities.

As I researched Will Steel for my lodge talk, I met with the Crater Lake Park Historian, Steve Mark. In my meeting with Steve Mark, he had a more nuanced view. He tends to choose his words very carefully. He would quickly acknowledge Steel’s impressive accomplishments. At the same time, I got the impression from Steve Mark that Steel was a self-promoting showman who could really alienate people while accomplishing great things for Crater Lake and himself. Again, Steel was a complicated man that would be wonderful to interpret for a park audience.

On the July 4th holiday weekend in 2006, my William Gladstone Steel lodge talk was ready. I even practiced it for a fellow ranger Dave Harrison the night before. Dave really liked my talk. He gave me some helpful tips for this talk that I use to this day.

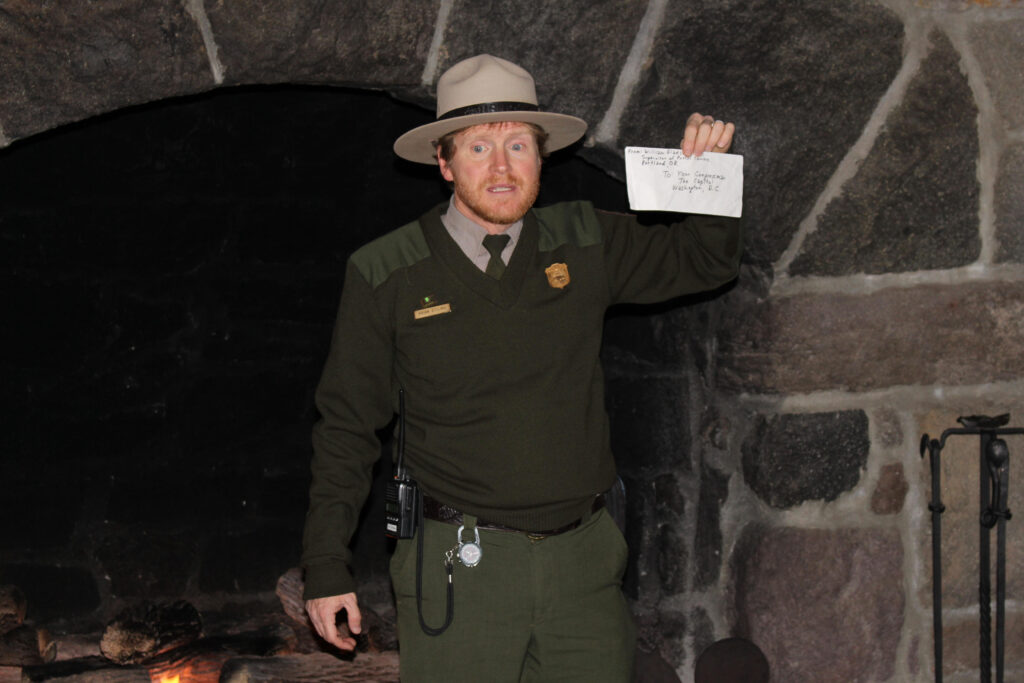

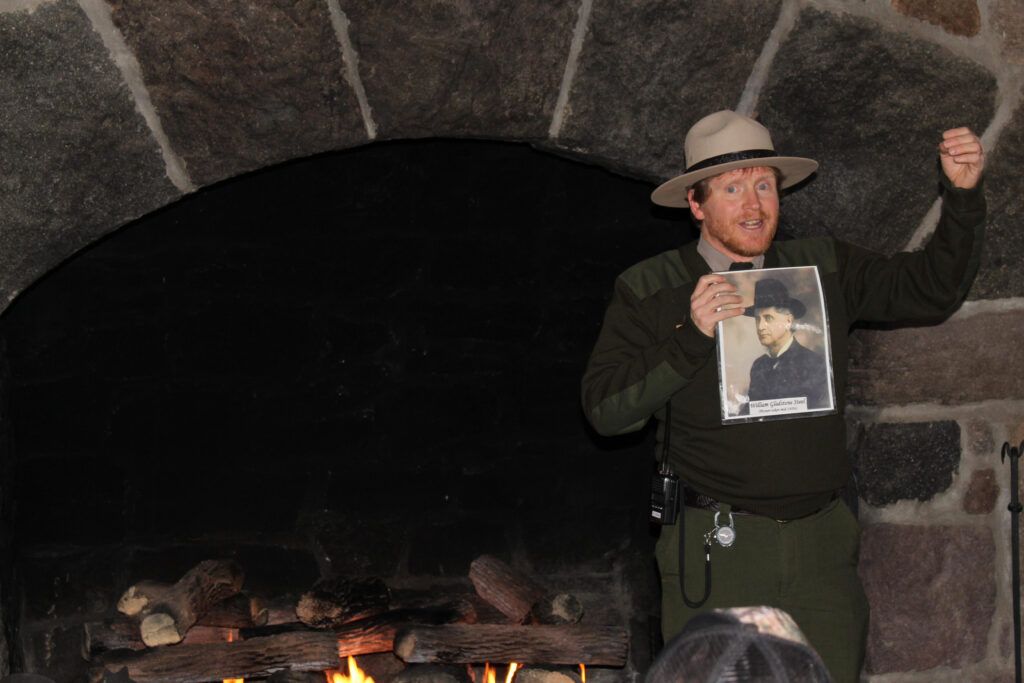

The title I gave my lodge talk was “Let’s Have a Toast to the Man of Steel!” The visitors seemed to love my talk. I received a very positive response from them. This talk was given on the back porch of the Crater Lake Lodge or inside in the Great Hall if the weather was cold, rainy, or snowy outside. Visitors would typically order alcoholic drinks from the Cocktail servers from the Lodge Dining Room. Steve Mark described it as ‘giving a ranger talk in a bar.’

That atmosphere intimidated some of my fellow rangers, but not me. In fact, I would even encourage my audience before I started my talk by saying: ‘Please order drinks because I have heard that my jokes are not funny when people are sober.’

That received a big laugh from the visitors who happened to be there. They could tell this would be a fun and entertaining program. My humor enticed them to stay for my entire talk.

Even more, I told my audience that the title of my talk happening at 4 pm was Let’s Have a Toast to ‘the Man of Steel.’ I explained that I would have a toast at the end of my talk around 4:20 pm. I even handed out plastic margarita glasses that I joked that I stole from my mom’s liquor cabinet. I informed them that I would not provide drinks to fill up those glasses. Even more, the glasses were dirty. I never washed them. They were just props. I wanted everyone to have glasses to give a toast at the end of my talk, especially the children.

Again, I did this to draw in an audience to my talk and work with this venue. I wanted to show that this would be a fun and historical talk where I would not be taking myself too seriously.

A couple of weeks later, lead ranger Dave Grimes saw my ranger talk. He was very impressed and full of praise for it. He thought it was so good that he thought we should video tape it. He suggested that we then send the recorded ranger talk to the NPS Interpretive Offices in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. If they approved, those rangers would then certify my lodge talk, which would look great on NPS job evaluations and ranger job applications.

Thus, Grimes recorded my 2006 talk. I later uploaded it to YouTube where you can see it here.

On February 27, 2008, The Stephen T. Mather Training Center for NPS sent a letter to Crater Lake National Park that this submitted ranger talk “demonstrates the certification standards.”

My lodge talk ranger “Let’s Have a Toast to the ‘Man of Steel!’”

In this next section, I posted the text from my Will Steel ranger talk that I gave at the back porch or inside of the Great Hall of the Crater Lake Lodge from the summers of 2006-2017. It is basically what I said in the YouTube video. I copied and pasted the transcript from the YouTube video, while also weaving in text that I thought improved this talk over the years.

“I am showing four o’clock on the nose here this afternoon.

I’m going to get started with my Ranger talk.

My name is Ranger Brian, and the title of my talk is let’s have a toast to the Man of Steel. We’re going to be talking about William Gladstone Steel who’s considered to be the founding father for Crater Lake National Park, the first man to research on the lake, our first concessionaire for Crater LakeNational Park and the second superintendent.

But before I go any further, I thought I would start off with an inaccurate historical reenactment that’s something that William Gladstone steel did to help make this a national park.

Picture this: the year is 1888 and William Gladstone Steel went to the headwaters of the Rogue River about 40 miles from us here. He then gathered up about 600 baby rainbow trout and he put them in a large milk bucket. (I demonstrated this by dumping Goldfish crackers into two plastic buckets filled neared the top with water)

He started transporting the fish in a horse-drawn wagon but the buckets were sloshing out too water on that bumpy wilderness terrain. He then decided to carry the full buckets by foot 40 miles up to the rim of Crater Lake.

Can you imagine what was going through his mind as he was doing this?

I know what’s going through my mind right now. Something like:

‘Boy are these buckets heavy but I still yeah 40 more miles to go.

I sure wish somebody would carry these buckets for me, but I guess it’s going be up to me! Oh wow! My back is killing me, and I still have 38 more miles to go.’

But just think: If I can get these fish in Crater Lake maybe fishermen will join me in the efforts to make this a national park. However, until then my back is still killing me.’

Well, you get the idea. He carried these fish up to the rim. In a sense, that was the easy part. There was no trail down a lake surface here in 1888 so he then hauled these fish by foot down a lake shore on these unstable rock ledges. He successfully planted 37 fish in Crater Lake.

Now what were you thinking as I was carrying these buckets:

‘Man, that ranger is crazy!’

The reason why I carried these buckets and expended all that energy was to demonstrate just a small fraction of energy that William Gladstone Steel took to make this a fabulous national park so we can enjoy this beautiful view from the back porch of the Crater Lake Lodge here today.

The planting of fish into Crater Lake was a success. NPS continued this tradition until 1941. Today, two different species of fish live at Crater Lake, rainbow trout and kokanee salmon.

Because of Will Steel, Crater Lake is now a fun place for fishermen. Since the fish are exotic and non-native, you don’t need a fishing license to fish in Crater Lake. There’s no size limit, number limit, and catch limit. You can catch as many fish as possible to your heart’s content, but you have to take them home with you. There’s no catch and release.

But William Gladstone Steel is so much more than just ‘the fish guy.’ He’s considered be the founding father of Crater Lake National Park.

So, who is this guy?

William Gladstone Steel was born in Stratford Ohio in 1854. As a schoolboy in Kansas in 1870, he claimed he read a newspaper article about this beautiful lake in Southern Oregon mountains called Crater Lake. This newspaper was wrapped in his lunch. He made a mental note that someday as an adult he was going to visit crater lake.

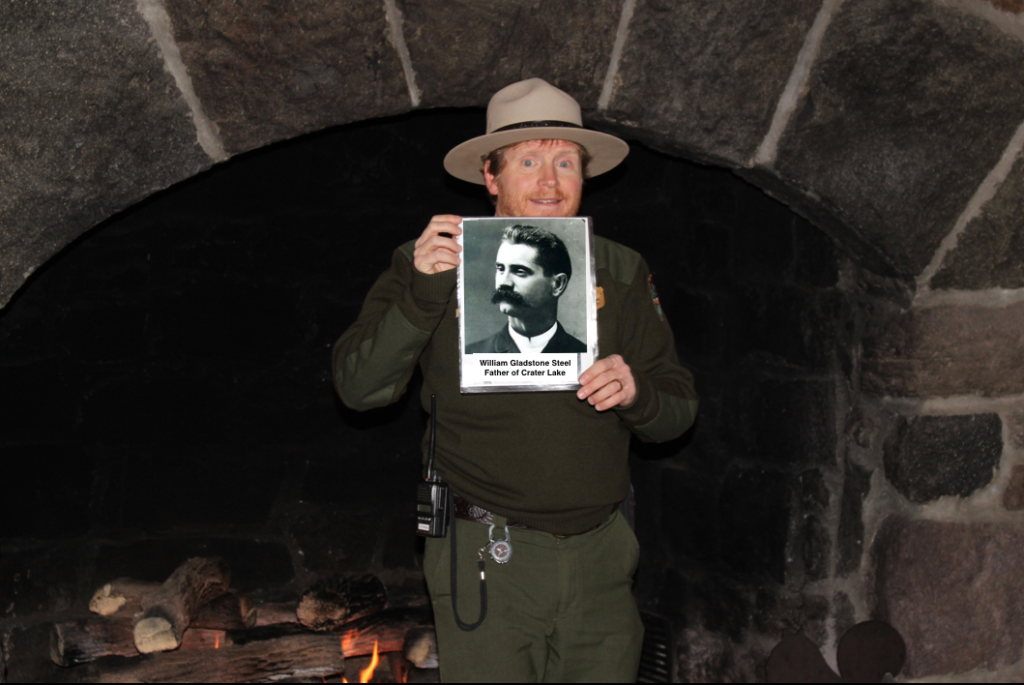

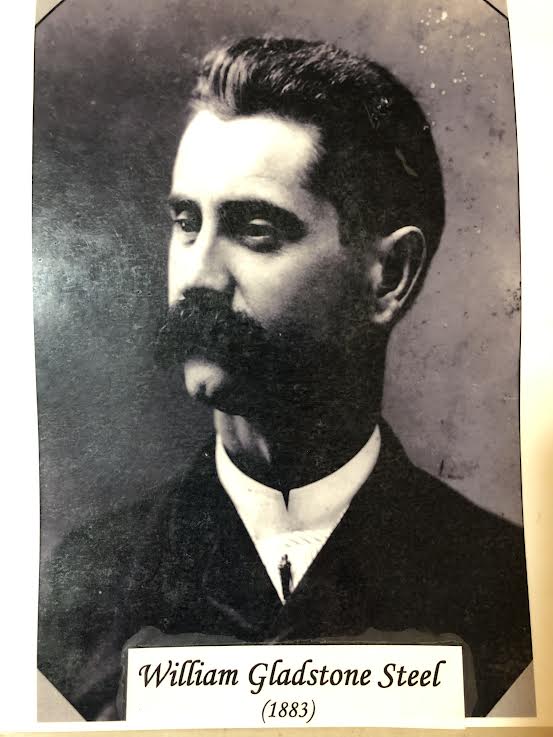

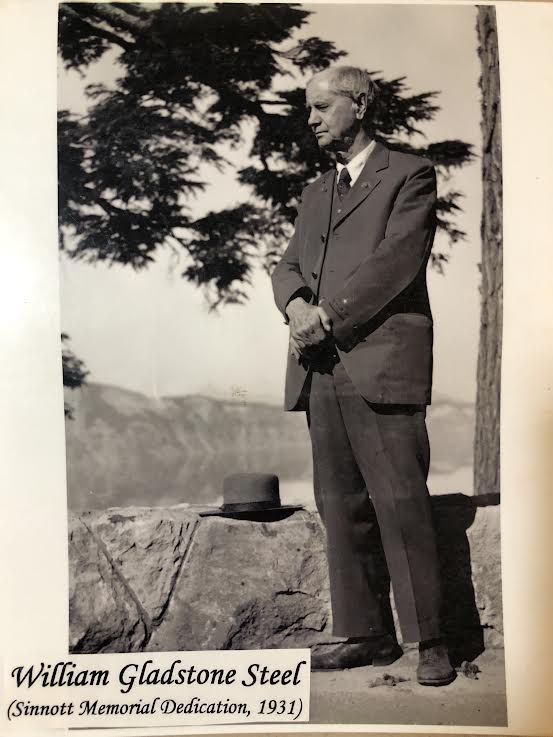

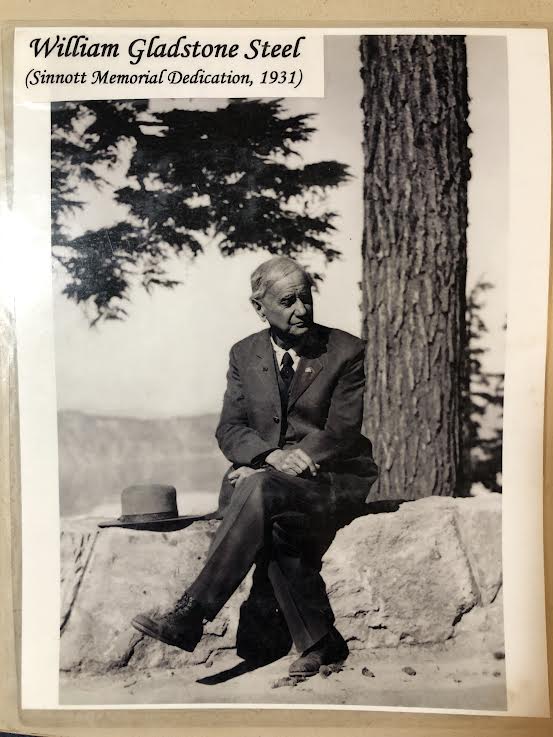

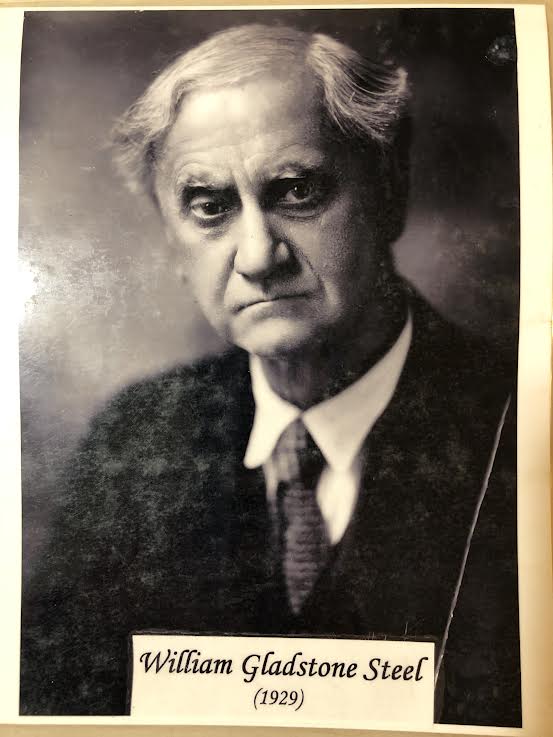

Well, in 1872 his parents moved to Portland, Oregon. Here is a picture of him. Isn’t he a handsome man, ladies? Our park curator thought so as she put together these pictures for me.

Finally, in 1885 he ventured to Crater Lake. He took the train down from Portland to Medford, Oregon. It took several days for him to get here by horse. The last couple hundred yards, he was so eager to see Crater Lake, that he ran ahead of his horse to get a look at the edge of the Rim. He saw it from around this area here where the Crater Lake Lodge is located here today.

On August 15, 1885, he saw Crater Lake for the first time. This is how he described seeing it:

“Not a foot of land about the lake had been touched or claimed. An overmastering conviction came to me that this wonderful spot must be saved, wild and beautiful, just as it was for future generations, and it was up to me to do something. How, I did not know, but the idea of a national park appealed to me.”

After William Gladstone Steel saw Crater Lake, it changed his life. When he returned to Portland Oregon, he started a petition drive. He got hundreds of signatures from friends, associates, and anyone he could find to start a campaign to make Crater Lake a national park. On top of that, he wrote close to a thousand letters nationwide basically every major magazine and newspaper in the country. He proclaimed to them that Crater Lake should be a national park.

Even more, he wrote every single member of Congress a letter trying to lobby them to make this a national park. However, none of these efforts were enough. William Gladstone Steele then had to make numerous trips to Washington DC to personally lobby senators and congressmen to make this a national park. He became such a fixture at the Capitol that senators and congressmen would duck around doors and hallways whenever they saw him.

They thought William Gladstone Steel as a pest and a crackpot. They probably even told at one point, ‘Will Steel, go home! Give it up! We are not going to turn your little lake into a national park!’

But Will Steel would not give up. He said at one point, “I got licked so often that I learned to like it!”

After 17 years of having a force of will and a persistent determination, Congress finally gave into Will Steel to get him off their backs. In 1902, Congress passed a law to make Crater Lake into a national park. President Theodore Roosevelt signed it into law on May 22, 1902. Today Crater Lake National Park is the fifth oldest national park in the United States.

William Gladstone Steel is quite a success story. But think about it. From the first time he saw Crater Lake until it became a national park, took 17 years of his life for his dream to come true. 17 years that’s a long time. It’s about the same amount of time it takes to raise a child from when they’re born until about the time, they’re ready to graduate from high school.

So, what does that say?

- It says that one person. Any one of us here today can make a difference.

- It also says never give up on your dreams, no matter how crazy they may be.

- It also says it may take an incredible amount of persistence and determination, as well as hearing a lot of ‘no’s for your dreams to come true.

That’s a great story by itself. But Will Steel is more than ‘the fish guy’ and the founding father of Crater Lake National Park. He was the first person to do scientific research on Crater Lake.

After he saw Crater Lake in 1885, he was determined to find out the lake’s depth. He applied and received funding from the U.S. Geological Survey to try find out the depth of Crater Lake.

Now the high-tech equipment in 1886 determined depth was a lead pipe, a piano wire, and hand crank. After he attained this equipment in Portland, he then three boats built up to survey the bottom of Crater Lake. He then had all this equipment shipped by rail from Portland down to Ashland. Next they had to use horse-drawn wagons to get this equipment up to Crater Lake.

Just right after they left Ashland and were Phoenix Oregon, Will Steel and the surveying party were heckled by a teenage boy. The boy told Will Steel, ‘I don’t know who built your boats, but they probably never seen a body of water before. Your boats won’t float on Crater Lake.’

William Gladstone Steel was not one to listen to his critics. He thought about what that boy said, and this is what he wrote in his book afterwards, ‘This brings to mind the fact that a critic is a person who finds fault with something of which he is densely ignorant.’

Kids, keep that in mind next time somebody makes fun of you. Or tells you your dreams can’t come true. They’re nothing more than a critic and a critic is no more than a person who finds fault with something of which he is densely ignorant.

It took over a week on those poor trails with those horse-drawn wagons, but they got the boats up to the rim around the Rim Village area. In a sense, that was the easy part because they had to get the boats from the rim to the lakeshore. It’s about a thousand feet down here so they had to use ropes and pulleys to slide the boats downhill. Will Steel later wrote that as they slid the boats downhill, it caused a few rockslides He claimed that was a rockslide just left of the boats. However, the boats made it safely the shoreline. The boats could float.

They used that lead pipe, piano wire and hand crank to do 168 soundings determine the depth. They determined in 1886 that Crater Lake was 1996 feet deep. It was the deepest lake in the United States and one of the deepest lakes in the world. We knew that as early as 1886.

Now 1996 feet deep sounds a little off, doesn’t it? In 2001 we used advanced sonar, and we now know the lake is 1,943 feet deep. Will Steel and his surveying party for about 53 feet off from today’s measurement. That sounds like a lot. However, if you do the math, they were only about 3% off as they knew an 1886 this was the deepest lake in the United States.

With that fact, they could more persuasively tell Congress this should be a national park.

Not only is William Gladstone Steel ‘the fish guy,’ the founding father of Crater Lake National Park and the first person to do research, but he is also the first concessionaire.

In 1902, after this became a national park, William Gladstone Steel hoped to become the first Park Superintendent. He figured he’d spent 17 years of his life blood, sweat, and tears trying to make this a national park. If you were a member of Congress in 1902 who would have been the logical choice to pick as the first Superintendent of Crater Lake National Park?

Will Steel, Of course!

However, many members of Congress then didn’t like William Gladstone Steel. They thought he was a pest, a crackpot, and a zealot so they were very happy to turn down his request. Understandably, William Gladstone Steel was very disappointed, but he was not going to be denied increasing the enjoyment of Crater Lake for himself or all of us here today.

In 1907, he formed the first concessionaire here and that year he started the campground at Mazama Village located roughly where it’s at here today. It was referred to as the Anna Springs Campground then. Besides the camping he also started the boat tours around 1907.

Back then, you would take a trail from the Rim Village area down to Lake Shore and then you take a rowboat out to Wizard Island. Besides the boat tours and the camping, he also started something else. Just curious: has anybody ever here ever been to the Crater Lake Lodge?

Yes, this is where we are at today. In 1909, Will Steel received funding from friends to start building the lodge. The original Crater Lake Lodge was constructed between 1909 to 1915.

This was how William Gladstone Steel this described all of his efforts as the park concessionaire, “All the money I have is in the park and if I had more it would go there too. This is my life’s work making Crater Lake accessible for folks because what good is scenery if you cannot enjoy it fully.”

So, in a sense, with fish to catch, boat tours and these comfortable rocking chairs, William Gladstone Steel but want us to have a completely fulfilling visit to Crater Lake. It’s as if he personally invited all of us here today with the rocking chairs, a nice place to have dinner in the dining room, a comfortable bed to sleep in here tonight, and the campground.

Besides all that, he also did one more thing to make this a fun national park to visit. Did anyone here drive up to crater lake from the outside?

Yes, all of us did. Unless you came in by helicopter or parachute. None of us would come up here without a good road system. In 1907, if you came to Crater Lake from Klamath Falls, it took about two full days by horseback. Today, it is little over one hour drive. Around that time from Medford, it took between three to five days to get here by horseback on those very poor trails.

In 1909, he pushed Congress to obtain road surveying funding so roads could be built to connect to nearby Oregon cities. He dreamed up a circular drive around Crater Lake so we can enjoy the views of the lake from many different angles. The original Rim Road received federal funding for construction between 1913 to 1916. The modern Rim Drive replaced it in 1934.

In a sense, with the road system, boat tours, these rocking chairs, and the lodge, it was as if Will Steel invited each and every one of us here today. He would want us to be able to admire and appreciate Crater Lake just as he admired and loved Crater Lake over 100 years ago.

I don’t want to give you the impression that Will Steel is a saint because he is not. He is human just like all of us here today. During those years when he was the concessionaire, he wasn’t satisfied. He was determined, even hell bent, to become the park superintendent.

He did everything he could to become superintendent, even starting false rumors about the first superintendent, William F. Arant. History shows William Arant was a decent superintendent but Will Steel rarely said anything nice about him. He used his connections to have William Arant removed. Arant knew he was being pushed out. Like any of us losing our jobs because of political means, William Arant was not going down without a fight.

He and his wife refused to leave his superintendent’s office. Even more, he refused to leave sitting at the chair at his desk. Therefore, two U.S. Marshals had to pick him up from his chair and toss him out into the street. He didn’t get the message the first time and went back inside the Superintendent’s residence. The U.S. Marshals then ejected him out of the home again.

If anybody drives into Crater Lake in from the south entrance, you might notice a sign for the Goodbye Picnic Area. That is literally the spot where the US marshals escorted out William Arant as the first superintendent. William Arant said ‘Goodbye!’ as defiantly as he could.

The park then said ‘hello’ to our second superintendent William Gladstone Steel. He was the Crater Lake Park superintendent between 1913 to 1916.

As we all know, unfortunately, what comes around goes around.

In 1916, Congress created a new organization to bring all the national parks under one government agency. It was called the National Park Service (NPS).

The first Director Stephen Mather did not like Steel’s antics. He wanted park superintendents loyal to him and the NPS mission. Mather did what he could to push out Steel.

Steel then used his political connections in Oregon to create the job of the Park Commissioner for himself. Steel would then be the official magistrate overseeing any federal court cases involving Crater Lake. It was just a ceremonial job. The only court case he ever heard was some teenage boys throwing rocks at people below them.

He now had a way to support himself for the rest of his life with his park commissioner salary. In one way, he felt blessed with all he was able to accomplish for Crater Lake.

At one point he said, “I set out what I accomplished to do and I’m now happy.”

At the same time, he felt like he did so much for Crater Lake. Yet, he felt kind wounded and empty towards the end of his life.

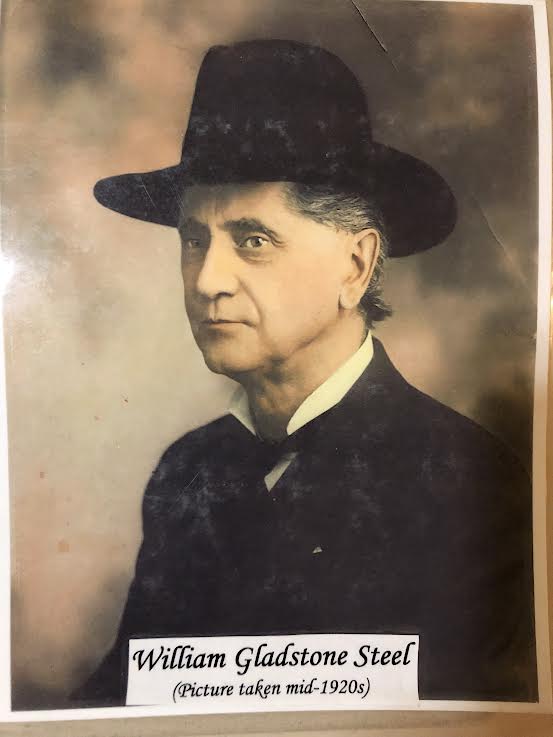

Do you remember the pictures of that dashing young man I showed you towards the beginning of my talk? Let me show you some pictures as he gets up in years. You will notice that he starts to look more stern, serious, and sad here as he advances in age. As he was getting up in years, he felt like he still had a lot of ideas for Crater Lake here.

In 1916, his friend Williams Jennings Bryant stayed at the lodge. He told Will Steel that ‘If you want to do boat tours you need to have an elevator that goes down to the lakeshore.’

Anybody who has taken a boat tour and walked down the 1.1 miles and the 700 foot drop on the Cleetwood Trail knows that’s a great idea. The National Park Service said ‘no’ to that.

When the Park was constructing the Rim Road, William Gladstone Steel wanted a section of the Rim Drive to go to the lake shore. He envisioned driving your car to Lake Shore to open up your car door and touch the water. Again, the National Park Service said ‘no.’

Besides the Crater Lake Lodge, Will Steel wanted to construct at least three more lodges, so more people had places to stay at Crater Lake. Again, the National Park Service said ‘no.’

Even more, Steel wanted a bridge out to Wizard Island so a driver could drive their car to the island and then drive to a big sprawling parking lot at the top. Again, NPS said ‘no.’

Will Steel was feeling more wounded as he got up in years feeling like the National Park Service and the public forget about him. He felt like he did so much to create Crater Lake National Park, protect research, and promote it. Yet, he felt was being forgotten about over time.

Maybe some of us could relate today. How many folks here are parents or even grandparents?

Do you ever feel like sometimes your kids fully don’t appreciate all the efforts and sacrifices you took to raise them?

That’s kind of how William Gladstone Steel felt. Again, he was born in Ohio in 1854 and he died in Medford, Oregon 1934. A couple of years before he passed away, he wrote, “My heart is full of sorrow of forgotten old man broken and condemned to solitude…I look across my little valley and see strangers and friends passing and review, but they know me not, neither do they care.”

Unfortunately, he felt like he was forgotten about towards the end of his life.

Well, in a moment we’re going to do what we can to correct this here today because we’re going to celebrate William Gladstone Steel with a toast.

So, grab your wine glasses, plastic water bottles, your beer bottles, my plastic margarita glasses, your paper cups, your coffee mugs, and your fish buckets. Anything you have here. Get ready because we’re going to do a toast here.

Everyone ready?

So, in conclusion, to William Gladstone Steel, The Father of Crater Lake National Park. He did so much throughout his life so we could enjoy this beautiful view from the back porch of a Crater Lake Lodge here today. Cheers!”

William Gladstone Steel information not included in my lodge talk

William Gladstone Steel had an amazing life story. My lodge talk felt like it wrote itself when I created it. However, I could not squeeze into my talk many fascinating aspects of his life. His parents were abolitionists when he was growing up in Ohio in the 1850s. They were anti-slavery zealots and this idealism rubbed off on Will Steel. As I would tell visitors in conversations, Will Steel became a zealot following his parents example, but he was a zealot for Crater Lake.

He was an idealist that hated the Ku Klux Klan when it was showing some prominence in Oregon during the 1920s. He enrolled his only child, his daughter Jean, into a Catholic High School in Medford, Oregon in the 1920s, and he was not even Catholic. He just wanted to thumb his nose at the KKK. Oddly, this was one of the very few things that we knew about his personal life.

He never talked about his wife Lydia Hatch that he married in Portland in 1900 or his daughter Jean Gladstone Steel, born in 1902. All his writings and numerous scrapbooks were all about Crater Lake. After my lodge talk, visitors wanted to know about his personal life and if he had any direct descendants. His daughter Jean took over the Crater Lake Park Commissioner job after Will Steel died in 1934, but she had no children.

As it was, my talk was very long. Sometimes it would go over 25 minutes for a 20-minute program. I tried to include my audience where I could with rhetorical questions scattered throughout the talk and the toast at the end. Plus, I sprinkled in humor where possible to share the oddities about Will Steel and myself. To my frustration, the limited time of this talk prevented me from sharing that William Gladstone Steel organized and founded the Mazamas. He established this mountaineering climbing club on the summit of Mount Hood in 1894.

The Mazamas, located in Portland, Oregon, promotes climbing, responsible recreation, and conservation values through outdoor education, advocacy, and outreach. Steel’s goal was to create a climbing organization run by climbers for climbers. He insisted that summiting a glaciated peak be a requirement for membership (a threshold that was removed by vote of the membership in January 2023). Remarkably, the Mazamas were never a ‘Boys Only Club.’ Women did not obtain the right to vote in Oregon until 1912. Yet, Steel designed the Mazamas in 1894 to be open to men and women as long they climbed a glaciated peak.

Crater Lake sits in a collapsed volcano that had an enormous eruption that imploded upon itself 7,700 years ago. Today the collapsed dormant volcano is referred to as Mt. Mazama. Steel organized a Mazama excursion to Crater Lake on August 21, 1896. One of their activities at Crater Lake was to hike up to the summit of Wizard Island to christen the volcano as Mt. Mazama. No doubt it was probably another way for Steel to get his mountaineering buddies to help his campaign to urge Congress to pass a bill to make Crater Lake a national park.

In 1885, to start his campaign to make Crater Lake a national park, I shared in my lodge talk that Steel “wrote close to a thousand letters nationwide basically every major magazine and newspaper in the country…Even more, he wrote every single member of Congress a letter trying to lobby them to make this a national park.”

It was tough to squeeze in my talk that Steel’s job in 1885 was the Supervisor of Postal Carriers in Portland, Oregon. This probably greatly helped his letter writing campaigns. Even more, I liked to joke during my talk that Steel might have even pressed some of his employees into his service to write Congress to make Crater Lake a national park.

Frequently, visitors asked me after my talk what Will Steel did for a living. I would respond that he was the Supervisor of Postal Carriers in Portland. According to Crater Lake historian Steve Mark, Steel also dabbled a bit in real estate. He never seemed to be a wealthy man. Any money he seemed to make went towards developing Crater Lake into a national park.

Steel seemed unbothered the way he offended people. This included the sheep herders, loggers, members of Congress, local southern Oregon residents, the first Crater Lake Superintendent William Arant, and the first Director of the National Park Service Stephen Mather in his singular obsession to turn Crater Lake into a national park with great roads and amenities for the park visitors. He wanted the best possible experience for tourists visiting Crater Lake. He was not afraid to step on toes of others who stood in the way for his vision for Crater Lake.

From 2006 to 2017, while I was a park ranger at Crater Lake, I never got burned out talking about Steel’s grit, determination, vision, tenacity, and singular focus to make Crater Lake into a wonderful national park to visit today. Will Steel was a fun lodge for me to present. I was always eager to give it since it was such an enjoyable experience for the park visitor and me.

Traveling to Everglades National Park for the winter from Crater Lake

When I gave this talk, I was always a political person looking how I can make the world a better place. I wanted to do this by somehow lobbying Congress to pass better policies, especially for climate change. I felt a kindred spirit with Will Steel with our deep love for Crater Lake, living life on my own terms, finding my passion and being a zealot about it, not caring what people think who don’t share my passion, and a ‘steel determination’ to make a difference in the world. While William Gladstone Steel’s single focus was to make Crater Lake a terrific national park to visit, my singular focus for over 15 years now is to make a difference for climate action.

I have always considered Crater Lake to be my place where my heart sings from when I first saw it in May 1992. However, Crater Lake was always a summer job for me. Because of the very snowy and long winters there, I could never find a way to get a permanent year-round job there. It’s also a very isolated place in the winter. I did get to work there into mid-November 1993 for the Crater Lake gift store and work from mid-March to May as an interpretive ranger for the Classroom at Crater Lake program. It was sublime to be there with all the snow.

At the same time, I felt like I got cabin fever with all the snow. It did not feel like an ideal match to work those jobs during those months. After enjoying Crater Lake for 6 months, I was typically eager to travel and work elsewhere during the winter months to see other beautiful places.

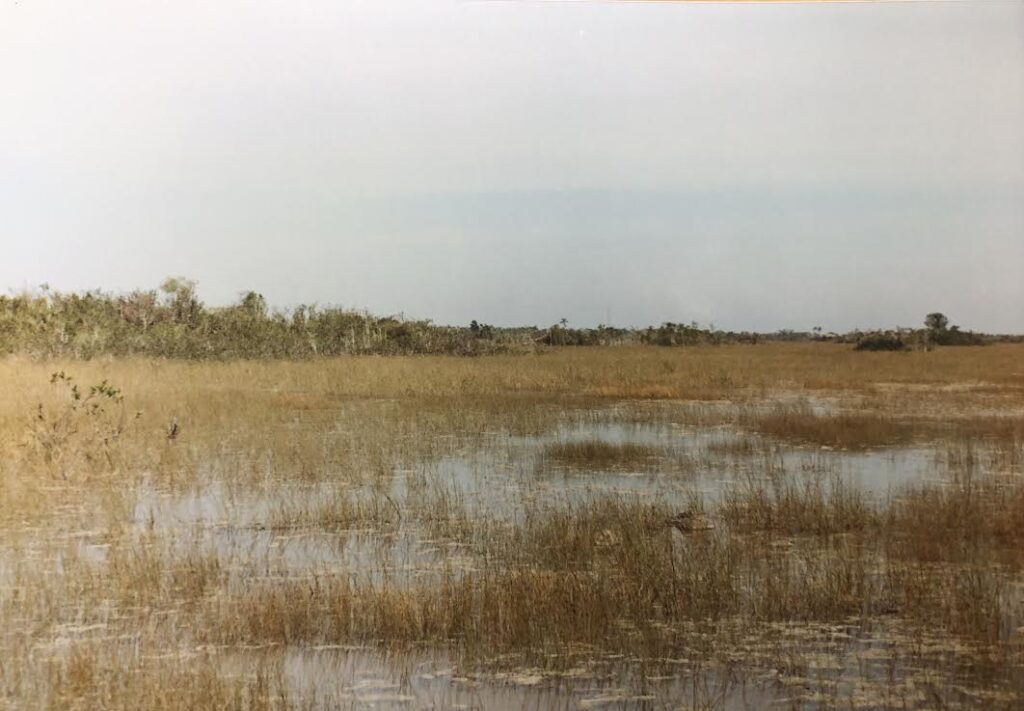

In my first winter away from Crater Lake National Park, I worked a season 1992-93 for the concessionaire, TW Services which then became part of the Amfac Corporation, at the Flamingo Outpost in Everglades National Park. After spending 6 months in the snowy mountains of Crater Lake, the Everglades was the exact opposite with a very flat landscape.

The highest point on the park road was just 3 feet above sea level. The majestic snowcapped mountains surrounding Crater Lake were a distant memory in the Everglades. Plus, when I arrived in December 1992, the weather was hot, humid, and muggy, the kind of summer weather I had escaped from my home state of Missouri to spend the summer at Crater Lake. When I looked out into the sawgrass prairie, one of the dominant landscapes of the Everglades, it looked no different than a bland Midwest farm field to me.

Moreover, I was picked up by a concession employee in Homestead, Florida. I had an amazing Amtrak two day train ride from St. Louis to Miami, Florida, arriving in mid afternoon. However, there was no friendly concessionaire employee to pick me up when I arrived. When I called the company, they said I was going to have to take a bus down to Homestead, located just outside of Everglades National Park. I was informed that they don’t pick new employees up at the train station or airport, just the bus stop in Homestead. I was not planning on taking a bus to Homestead and I was livid. I wanted to immediately turn around and spend the winter with my parents in St. Louis. However, something told me not to do that to give this experience a try.

Arriving in Homestead that evening, it looked like a war had just been fought there. Hurricane Andrew destroyed the area just three months earlier. The city still had piles of debris and not much electricity making it a very dark place to meet someone at night. I had never seen an aftermath of a natural disaster, and it looked very creepy and bleak. When we drove into the Everglades late that moonless night, it was very dark outside. It felt like I was being driven into the depths of hell. I wanted to turn around and leave, but I did not know how. With his love of Crater Lake, I don’t think that Will Steel would have liked to have been in this situation either.

Everglades National Park inspires me to take Climate Action

At the same time, I make the most of this time working in Everglades National Park. In February 1993, I even went on an overnight canoe trip in a mangrove creek called Alligator Creek with friends Jim and Rob. This felt like an Indiana Jones experience to be canoeing in the mangrove creeks where the trees would form a canopy overhead, making me feel like I was going to be swallowed up by the Everglades. The mangroves have a lot of dissolved muck at the base of their watery roots which gives off a hydrogen sulfide smell, like rotten eggs. We were irritated by mosquitoes at times during this trip in the mangrove creek and at our shoreline campsite that evening. The mosquitoes got so bad that we made a campfire at night not to stay warm by to stand close to it to try to get some relief from the mosquitoes.

We saw an alligator or two during this trip, as I did nearly every day that I worked in the Everglades. However, alligators don’t like to live in the brackish saltwater mixture of the mangroves. They prefer the interior freshwater areas in the Everglades and throughout Florida. When we spotted an alligator, Jim would humorously say, “Alligator Creek lives up to its name!”

Jim said it often enough that Rob and I started laughing and would later on impersonate the way he would say that. In the middle of this trip, we did see the endangered American Crocodile. It laid totally still on an embankment by the mangrove shoreline. It wanted to regulate its body temperature, like all crocodilians do, on a warm day. At the same time, it had its mouth open so the salvia on its tongue could cool off its head, similar to how us humans sweat on a hot day. The mangrove creek was only about 8 feet wide. There was not much room when we were paddling down the creek getting close to it. When we got too close, the shy crocodile wanted no part of us. It jumped in the water and disappeared faster than you could blink.

I am glad that I did not give up on the Everglades from my first impression. The area started to grow on me. Like discovering the stories of Will Steel determined to make Crater Lake into a national park around 1902, I started reading about Marjory Stoneman Douglas. She is considered to be the mother of Everglades National Park. I remember seeing some TV show about her when I was growing up in Missouri. I became intrigued about her. She was still alive then at the age of 102 and still making public statements how the Everglades must be protected.

In my spare time, I read her 1987 autobiography Voice of the River. I found her book to be very inspiring, insightful, and even humorous. Like William Gladstone Steel, Marjory Stoneman Douglas became another huge hero of mine and deep influence on my life. At that time, I was religious, but I loved her ending sentence in her autobiography, “I believe that life should be lived so vividly and so intensely that thoughts of another life, or a longer life, are not necessary.”

Unlike the love at first sight when I first saw Crater Lake, it took time for me to develop a love and deep appreciation for the Everglades. Looking at the Everglades through the eyes of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, as well as my mentor Steve Robinson really helped.

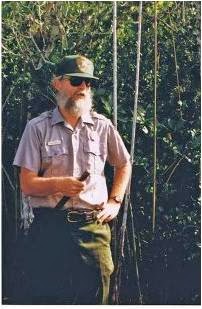

Steve was a fourth generation Floridian, originally from the Tampa Bay area, who worked seasonally in Everglades National Park for 25 years from 1980 to 2005. He was an amazing storyteller about the Everglades and nature that people flocked to see his ranger talks. Ironically, Steve started working as a summer interpretation ranger at Crater Lake National Park in 1993. Like me around that time, he was spending his summers at Crater Lake and his winters in the Everglades. With his long hair and long beard, he looked and talked like Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax.

Steve had a deep knowledge of the Everglades with enchanting stories to go with it, that I would hang onto every word he said. Everyone else I met who knew Steve did the same. Even when I strongly disagreed with Steve, I still thought he had a very valid, well-thought-out point of view that was worth considering. For instance, he was no fan of William Gladstone Steel. Steve did not think Will Steel was a worthy conservationist or should be put on a pedestal as ‘The Father of Crater Lake National Park.’ He thought of him as nothing more than a carnival huckster like P.T. Barnum. Steve did not like how Steel pushed so hard to be the concessionaire at Crater Lake and wanted to make a lot of money as the Crater Lake concessionaire.

On the other hand, Steve thought Marjory Stoneman Douglas was someone to be admired and emulated. He met Marjory years ago by chance while working as an Everglades ranger. He was very impressed with her. He found her to be very humble, knowledgeable yet self-confident in his brief conversation with her. I spent hours at Steve’s park housing residence in Flamingo and Crater Lake hanging onto every word that he told me. Fortunately, Steve’s wife Amelia and their young son Darby did not mind my frequent presence to learn from Steve.

I found the stories of the Everglades, especially in the Flamingo area, to be very captivating. I loved all the wildlife I in the Everglades, such as the alligators, crocodiles, dolphins, manatees, and the wide variety of birds. By April 1993, I was eager to return to Crater Lake. However, the Everglades, especially the Flamingo area drew me back to work there again in the winter of 1995-96 and again during the winter of 1997-98.

My first winter, 1992-93, I started working in housekeeping for the Flamingo Lodge and then moved my way up to a Front Desk Clerk Position. In the winter of 1995-96, I tried working as a night auditor at the Flamingo Lodge. I made it through the season, but it was not my cup of tea. That time, I brought my girlfriend Sheila with me, and she enjoyed working there with me at the Flamingo Lodge. We then returned to work there for the winter of 1997-98.

By 1998, I saw the concession naturalist guides looking like they had a great time narrating the boat tours. I wanted to work that position and jumped at the opportunity when an opening happening in January 1998. By this point, I had worked in the Everglades for several seasons, but I still knew so little about the birds, the history, the ecology, and other subjects that the visitors wanted information. I spent those first few months reading, studying, and cramming all I could to appear as a competent and well-versed naturalist guide.

As I have blogged about before, I became concession naturalist guide on the boat tours in the Everglades in January 1998. Soon afterwards, visitors started asking me about global warming. I knew next to nothing about that subject. Visitors hate when park rangers and naturalist guides tell you, “I don’t know.” Soon afterwards, I rushed to the nearest Miami bookstore and the park library to read all I the scientific books I could find on climate change.

I learned about sea level rise along our mangrove coastline in Everglades National Park. It rose 8 inches in the 20th century, four times more than it had risen in previous centuries for the past three thousand years. Because of climate change, sea level is now expected to rise at least three feet in the Everglades by the end of the 21st century. That would swallow up most of the park and nearby Miami since the highest point of the park road is three feet above sea level.

It really shocked me that crocodiles, alligators, and beautiful Flamingos I enjoyed seeing in the Everglades could all lose this ideal coastal habitat because of sea level rinse enhanced by climate change. I just did not know what to do about it.

I enjoyed my job as a year-round naturalist ranger at Flamingo in Everglades National Park. However, by the spring of 2002 I was burned out of that job. I wanted something new. In the winter of 2003, I worked as a seasonal interpretation park ranger at the Everglades City Visitor Center at Everglades National Park. From 2003-07, I enjoyed this winter job of narrating the boat tours, leading guided canoe trips, giving ranger led bike tours of Everglades City, giving ranger talks, and creating an evening presentation on the birds of the Everglades.

My supervisor at Everglades City offered me a choice for the winter of 2007-08 to return to Everglades City or work as a winter seasonal interpretation ranger at Shark Valley Visitor Center in Everglades National Park. I always had enjoyed taking the Shark Valley Tram Tour or renting bikes to traverse on the 15-mile Tram Road. With the man canal next to the west side of the Tram loop, it was a great waterway to see alligators and many wading birds.

During that winter, I became so worried about climate change that I could not sleep at night. In the spring of 2008, I quit my winter job in Everglades National Park. In 2009, I started spending the winters in my hometown of St. Louis, MO to start organizing for climate action. I did not know what to do, but I was determined I was going to make a difference for climate action.

Becoming a climate change organizing zealot in Missouri and Oregon

By 2009, for seventeen years, I had worked as a seasonal park ranger at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon in the summers. Everglades National Park, Florida was where I worked in the winter up until 2008. Two years before, in 2006, I became an interpretive park ranger at Crater Lake. I absolutely loved my job as an interpretation ranger at Crater Lake giving ranger talks, guided hikes, leading evening campfire talks, and narrating the boat tours. I loved every minute of standing in front of an audience, in these iconic places sharing about nature.

2006 was also a pivotal summer for me because I saw in a nearby movie theatre the climate change documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, about former Vice President Al Gore. That documentary lit a spark to do something about climate change, but I did not know what to do.

This climate change calling went for years without an outlet to act. In 2009, I gave myself the title of The Climate Change Comedian on a dare from a friend in Ashland, Oregon. While spending the winter of 2010 in St. Louis, my sisters booked me to give ranger/climate change talks at my nieces and nephews schools, and for their boy and girl scout groups. A family friend in St. Louis helped me develop my own website www.climatechangecomedian.com, which is still active today. That same winter, I created my own climate change PowerPoint talk, Let’s Have Fun Getting Serious about Solving Climate Change.

In the spring of 2010, I gave this PowerPoint talk with friends in St. Louis. In August 2010, I showed it to fellow rangers at Crater Lake National Park. In February 2011 while spending the winter in St. Louis, I joined South County Toastmasters to improve my public speaking skills and follow my ambitions to be a good climate change communicator. That same month, I started writing this blog and posted two entries that month.

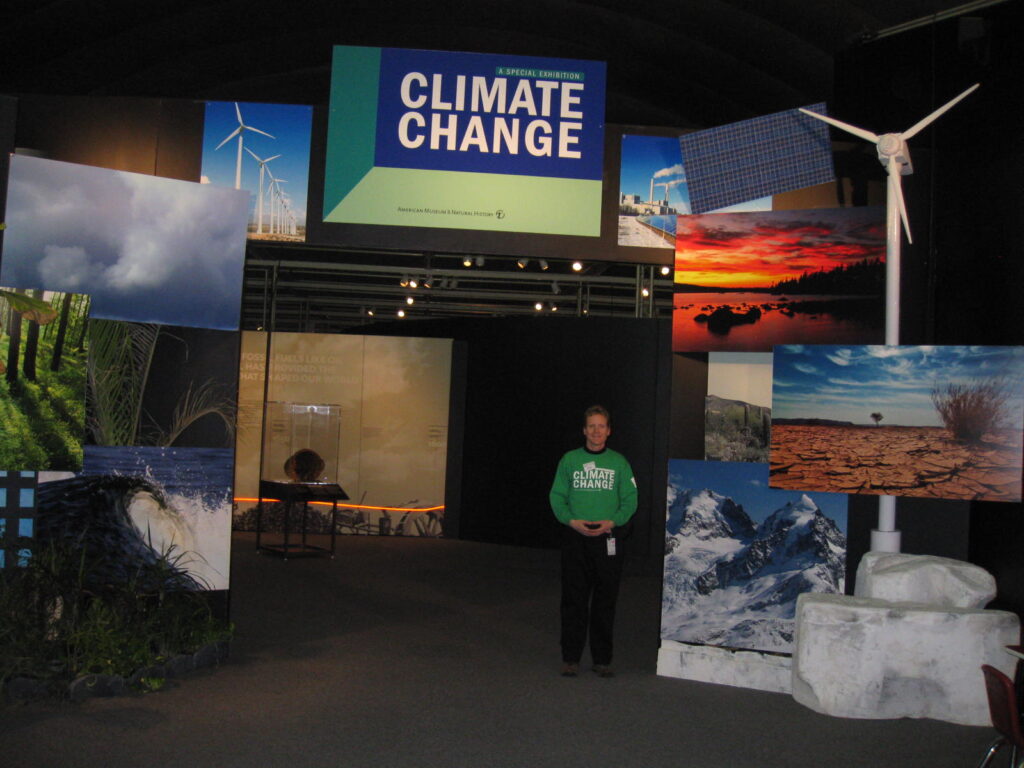

From March to May 2011, I worked at the St. Louis Science Center at their Climate Change exhibit. For years, I didn’t feel like I knew enough to talk to Crater Lake visitors about climate change and give ranger talks about it. That changed in August 2011, I was finally brave enough to debut a climate change evening campfire ranger talk called The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, which I recorded for YouTube in 2012.

I felt very scared when I started giving this climate change talk at the Crater Lake campground Amphitheatre for audiences of up to 100 visitors. I was very afraid that I would get visitors who would want to argue with me about climate change and debate the science. Actually, the opposite happened. The park visitors were very appreciative and gave me a lot of positive feedback. I loved giving this climate change evening program at Crater Lake until I stopped working there at the end of the summer of 2017. Hopefully, Will Steel would have been proud of my climate change evening talk. I shared how climate change impacted Crater Lake. I then encouraged my audience to take action to reduce the impact on Crater Lake and our national parks.

During the winter of 2011-12, a friend Larry Lazar and I co-founded the Climate Reality Meet-Up group (now known as Climate MeetUp-St. Louis). I met Larry the previous spring when I worked at the Climate Change exhibit at the St. Louis Science Center. In December 2011, we held our first monthly gatherings with speakers to learn more about the science of climate change and how we could act on climate.

Becoming a volunteer Climate Change Lobbyist

One of the guest speakers who came to our Climate Reality Meetup group during the winter of 2012 was Carol Braford. Back then, Carol was the St. Louis group leader with Citizens Climate Lobby (CCL). Carol is still active to this day with CCL as the Midwest or “Tornadoes” Regional Coordinator. During the winter of 2012 at Climate Reality Meet Ups, Carol Braford was the very persistent with me that I should come to a monthly Citizens Climate Lobby conference call. I even blogged about Carol in January 2013, Want to change the world? Be Persistent!

I attended a CCL meeting at Carol’s home in April 2012 and immediately became hooked. I then volunteered with CCL for over 10 years. During the summer of 2012 while I was working at Crater Lake, my goal was to start a CCL chapter in Ashland, Oregon. I perceived Ashland as a very progressive community that cares deeply about the Earth and natural environment. I thought it would be a great fit for a CCL group. Plus, I wanted to have a local CCL chapter that met while I was spending my summers working at Crater Lake. In January 2013, my friend Amy Bennett called to inform me that the southern Oregon CCL chapter that still meets in Ashland, Oregon had been established. To this day, it’s one of my proudest accomplishments.

I started to embody Will Steel’s energy, vision and determination as I threw myself into volunteering for CCL for climate action. Like Will Steel, I wrote letters to the editor and opinion editorials (op-eds) to newspapers to urge members of Congress and the public to support CCL’s carbon fee and dividend policy. I was so proud when my first op-ed was published in my hometown newspaper the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on April 19, 2013, For Earth Day, a GOP free-market solution to climate change. One year later, for Earth Day 2014, the Post-Dispatch published another op-ed I wrote, For Earth Day: Asking our elected officials to be climate heroes.

On one my cross country drives from St. Louis to Crater Lake, I was invited to be a guest speaker at Grand Canyon National Park on May 13, 2013. I gave my Crater Lake climate change evening program to an audience of over 200 park visitors and staff at the Shrine of the Ages Auditorium. This was my biggest audience ever for a climate change presentation.

In July, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published my op-ed, What Keeps Me Up Late at Night. In October, I was on a roll getting climate change op-eds mentioning Crater Lake published in newspapers across Oregon, such as the Klamath Falls Herald and News, Medford Tribune, Grants Pass Daily Courier, Bend Bulletin, Eugene Register-Guard, the Salem Statesman Journal, Ashland Daily Tidings, and Oregon’s largest newspaper in circulation, the Oregonian, out of Portland, Oregon. In 1885 after he saw Crater Lake, Will Steel wrote to newspapers across the United States in his campaign to make Crater Lake into a national park. I did not match Steel’s efforts to submit letters to the editor in newspapers across the U.S. However, I did get published in newspapers across Oregon in 2013. Hopefully, Will Steel was impressed.

As I blogged about previously, in August 2013, I joined with friends with the southern Oregon Chapter of CCL in lobby meetings with the Medford, Oregon office district staff of then Republican Congressman Greg Walden (OR-02) and Democratic U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon. I remember it as a fun and empowering experience, even if we could not find much agreement in our meeting with Walden’s Deputy Chief of Staff. Merkley’s staff was pleasant and totally agreed with us that climate change is a huge concern. However, neither Congressional staff did not seem to have much to say about the carbon fee and dividend policy.

Those Oregon lobby meetings inspired me to organize my own lobby meeting when I spent the next winter in St. Louis. I organized first my first lobby meetings with the district office of my Missouri Republican member of Congress, Rep. Ann Wagner (MO-02), on February 14, 2014. I don’t have memories of what was said in that meeting, since so much time has passed. However, I remember it being a great experience that we respectfully listened to Rep. Wagner’s staff, and they listened to us. We agreed to meet again in the future to have more discussions.

In a sense, I loved organizing and attending CCL lobby meetings with Congressional staff that it energized me to travel 8 times from 2015 to 2019 to lobby Congressional offices for CCL for climate action, specifically their carbon fee and dividend policy. In November 2015 and 2016, I flew from St. Louis to Washington D.C, which was roughly a two-hour flight each direction.

When my wife Tanya and I moved to Portland, Oregon in February 2017, it would take me all day to fly to Washington D.C. I would typically catch a 5:30 am to 6 am flight from Portland and arrive in Washington D.C. very late that afternoon or evening. It was amazing to travel that quickly across a continent. When William Gladstone Steel made his numerous trips from Portland, Oregon to Washington, D.C. from 1885 to 1902, there were no airplanes and airports then. He would be riding trains across the United States. No doubt these trips would take several days to get there. I can’t image the sacrifices he took to travel all the way to Washington D.C. and back on those trains to lobby in Washington, D.C. After I moved to Oregon, I marveled at his dedication and determination to take lobby trips in the era he lived before modern air travel.

I loved every moment lobbying in Washington D.C. In November 2016, Tanya and I had the thrill to also lobby elegant Parliamentary offices in Ottawa, Canada for Citizens Climate Lobby Canada. I relished the excitement of putting on my best and only dress suit to take the DC Metro commuter trains to the U.S. Capitol. Then seeing the iconic U.S. Capitol Building up close.

Once I would pass through security to enter the Congressional Office Buildings, it was a fun corn maze to try to find specific Congressional offices where I had scheduled meetings with Congressional staff. It was fun to plan the lobby meetings with other CCL volunteers attending the meetings with me. It was always enjoyable to meet with the Congressional staff to listen to where they are at with climate policies and then petition them to support our carbon fee and dividend bill. I enjoyed the debriefing meetings with the CCL volunteers afterwards and then writing thank you cards which I then dropped off at the Congressional Offices.

I wonder if Will Steel had as much fun as I did. However, he probably did since he traveled to Washington D.C. so many times. Even more, he did not take it personally when members of Congress would tell him no to his request to make Crater Lake a national park. After all, he famously said, “I got licked so often that I learned to like it.”

My highlights as a volunteer Climate Change Lobbyist

Citizens Climate Lobby (CCL) trains their volunteers for the Congressional Lobby days to be respectful, grateful, and appreciative when we lobby Congressional staff and members of Congress. Even more, they want us to be more interested in what the Congressional staff and members of Congress are saying than what we have to say. As a result, over the years, CCL has established a reputation on Capitol Hill of being friendly, appreciative, and great listeners.

Thus, members of Congress and their staff would say that they enjoyed and looked forward to their lobby meetings with CCL. I had conservative Republican Congressional staff, who I probably did not see eye to eye much with them on policy, tell me how much they liked meeting with me. I especially heard this from the staff of GOP Rep. Ann Wagner. When I spent my winters in St. Louis volunteering with CCL from 2013-2017, I lived in Rep. Wagner’s district. I worked very hard to develop a good rapport with her Ballwin Missouri office and Washington D.C. staff.

The last time I lobbied her Ballwin MO office in March 2017, I brought homemade chocolate chip cookies from my mother-in-law Nancy. At first, the staff was hesitant to take them fearing that the cookies were store bought and I spent a lot of money buying them. They did not want to be perceived as violating ethical rules for accepting expensive gifts. Only when they fully realized that the cookies were homemade and not a paid gift, they started devouring the cookies. I wonder what Will Steel would have thought about my homemade cookies as lobbying gifts.

In November 2017, I let Congresswoman Ann Wagner’s office know I had moved to Oregon, I was no longer a constituent, and I might not be lobbying her office anymore. The Legislative Assistant was very complimentary saying that I was still more than welcome to come lobby their office anytime. I found that comment to be very heartwarming.

All my lobby meetings in Washington D.C. and in the local Congressional offices were always with Congressional staff. The exception to this was when I went to a ‘Missouri Mornings’ coffee gathering in U.S. Senator Roy Blunt’s office. This was a more coffee meet-and-greet where Missouri constituents who happened to be in Washington D.C. could stop by Senator Blunt’s Congressional Office to briefly meet him, shake his hand, and get their picture with him. I did go one time. The picture taking and interaction with Senator Blunt was so brief that I was not able to urge him to support climate legislation. However, this meeting was another great opportunity to chat hand an offhand conversation with his staff to urge his support for climate legislation.

In November 2016, I signed up for a similar office meeting with U.S. Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri. Her morning coffee meeting seemed to be open to any citizen wanting to discuss politics and policy with her. She had a female group of Georgetown University Law students in the meeting with her, as well as a couple of constituents from Missouri like me. She gave great career advice to the female law students. She urged them to get more involved in politics because we do need more women in politics.

Each of us at the coffee table shared why we were there. When it came to my turn, I stated it was because of climate change. This meeting happened just two weeks after the November 2016 Presidential election where Donald Trump was just elected President. Claire very angry how voters had chosen Republicans in Missouri and nationally. She remarked, “I hate to be less than lady like and say this but, here it goes. To me, it felt like voters in Missouri and middle America gave the Democratic Party the middle finger.”

After I shared my concerns about climate change, she retorted, ‘Good luck with anything good happening with climate policies for the next four years.’ Shen pointed her finger at me and snarled, ‘Oh, the Keystone XL pipeline will definitely be passed now.’

Sadly, Senator McCaskill was a supporter of the tar sands oil pipeline which would have gone from Alberta Canada down to Texas and Louisiana to the oil refineries there. It was a disappointment that she was still a strong supporter of that policy and she felt so pessimistic about climate policy with Trump becoming President in a few months. Thus, it was not a productive meeting for me to urge her to support CCL’s carbon fee and dividend policy. However, I still felt very happy that I was able to talk to her directly about supporting CCL climate policies, even if she was not in the mood to listen.

Besides my very brief interactions with Senators Claire McCaskill and Roy Blunt of Missouri, all my Washington D.C. lobby meetings were with Congressional staff. While that might disappoint some people who want to directly lobby their members of Congress for a policy, I was perfectly fine with meeting with Congressional staff. After all, Congressional staff has the ear of the member of Congress and regularly interacts with them. If the Congressional staff does not like to policy or bill you are advocating, they will probably advise the member of Congress not to support it either. On the other hand, if the Congressional staff likes your policy, you may have a powerful ally that can help sway the Representative or Senator to support your position.

This happened to me in June 2019 when CCL volunteers and I met with the Washington D.C. Congressional staff of Rep. Fredericka Wilson, Florida District 24. We had a very productive conversation with her Legislative Correspondent, Devin Wilcox. Devin seemed very supportive of the CCL carbon fee and dividend bill we were urging her to support, known as the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act (EICDA). I very distinctly heard Devon say towards the end of the meeting that he felt his boss Rep. Wilson could easily co-sponsor our bill.

The Florida CCL volunteers, and CCL Washington D.C. staff stayed in touch with Devin for months afterwards. I stayed in touch with the Florida CCL volunteers to make sure they were in contact with Devin regularly. That June 2019 meeting, plus CCL volunteer and staff follow up conversations with Devin led to Congresswoman Frederica Wilson to join with 96 of her U.S. House colleagues to co-sponsor the EICDA on February 24, 2020.

Unlike William Gladstone Steel, I was not able to get Congress to create a Crater Lake National Park in my years of climate lobbying. However, I still felt like such a sweet victory when I was part of the effort that led to Rep. Wilson co-sponsoring a climate bill.

Lobbying Oregon Legislators for Climate Action

In the summer of 2018, I started volunteering with Renew Oregon with their efforts to work closely with Oregon state legislators to pass a cap and invest bill. For Renew Oregon volunteers like me, much effort would be needed to regularly lobby state legislators to urge them to make passage of the cap and invest bill a high priority.

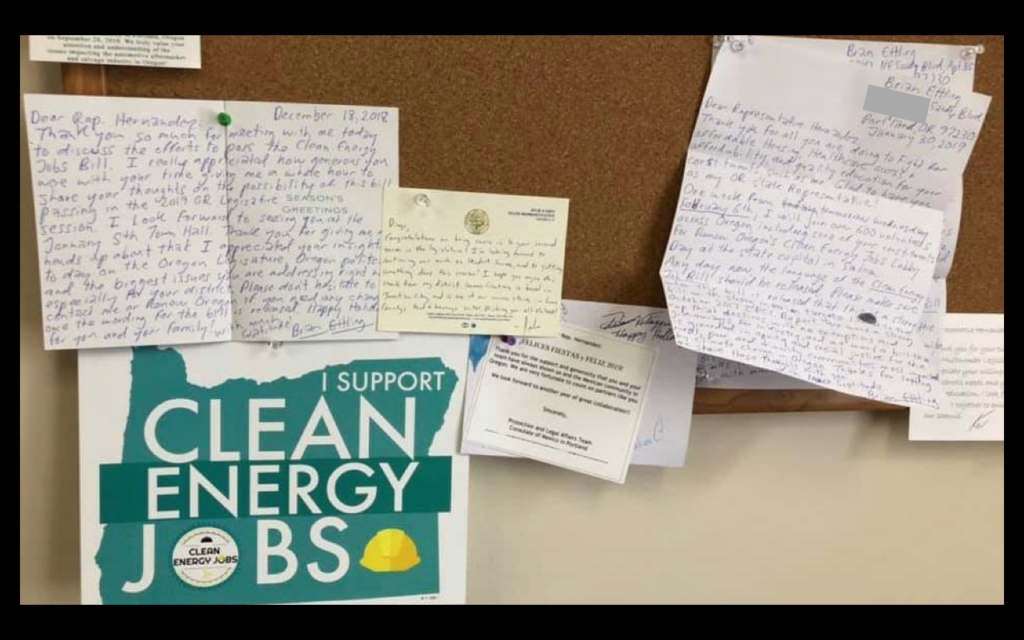

That summer, I also started writing letters to my Oregon Representative Diego Hernandez. I met him for the first time on September 25, 2018, on a legislative working day at the Oregon state Capitol. I always enjoyed my interactions with him. We had a great rapport. Diego was always very supportive of my climate lobbying and organizing.

Periodically, I sent him letters and cards urging him to support the cap and invest bill, which became known as the Clean Energy Jobs Bill or HB 2020 in the 2019 Oregon Legislative session. From my conversations with him, I had no doubt that he would vote yes on these climate bills.

On February 6, 2019, Renew Oregon had a lobby day at the Oregon state Capitol to meet with the state legislators to urge them to support The Clean Energy Jobs Bill. When I met with Rep. Hernandez inside his office, he said, ‘Look right behind you, Brian.’

When I looked right behind me on his bulletin board, he had attached with push pins all the letters I sent him over the previous months. There were at least 3 letters from me. Apparently, Diego liked to display letters from constituents, and most of the letters tacked up on the bulletin board were from me. This showed me very clearly that elected leaders do read letters from constituents and hang on to them when considering policy decisions and votes.

Rep. Hernandez laughed with delight as I was amazed seeing my letters and taking pictures of them hanging from his bulletin board. He continued to be very supportive of my climate lobbying and strongly supporting the climate bills I advocated. He probably would have supported those bills even without my lobbying. However, I think he liked that he had constituents like me cheering him on and strongly urging him to support climate legislation.

Sadly, Rep. Diego Hernandez resigned from office on March 15, 2021 due to sexual harassment charges filed against him from staff and lobbyists at the Capitol. The House Ethics Committee planned to recommend a House floor vote to expel him. We must believe the women and I thought he should be fully accountable for his actions. I was very disappointed that he did not act in a professional manner towards women in his position of power. I considered him to be a friend. I texted him on the day he resigned to offer that I am there for him if he ever wanted to talk. It was sad and totally understandable why he had to resign from the legislature.

While lobbying state legislators with Renew Oregon in 2019-2020, I built very good relations with other state legislators in the Oregon House and Senate. As I blogged about previously, during the summer of 2020, I held Zoom and phone meetings with Oregon Legislators that I met during my lobbying for the 2019 and 2020 cap and invest bills. As a Citizens’ Climate Lobby (CCL) volunteer, I urged them to endorse the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act (EICDA).

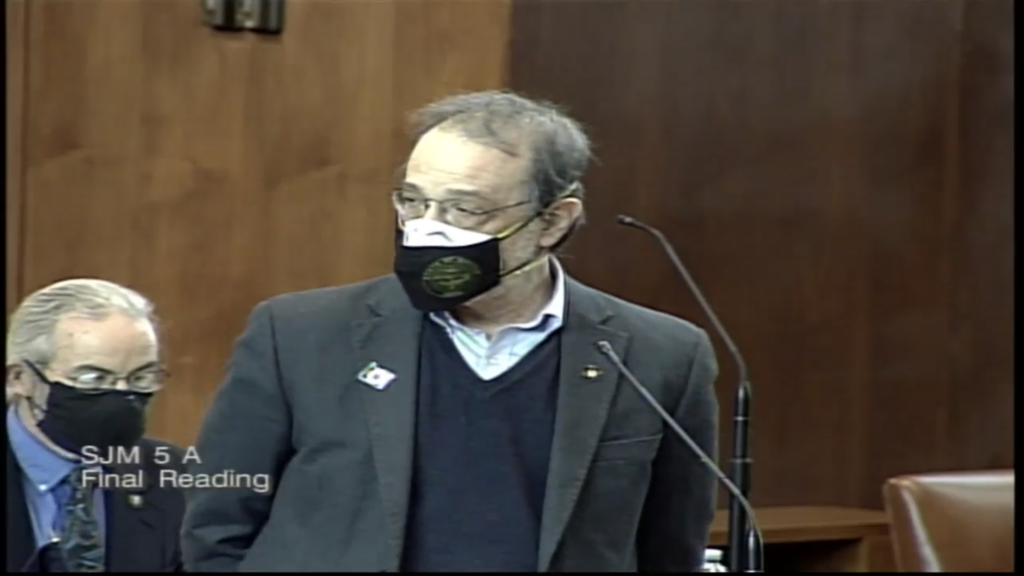

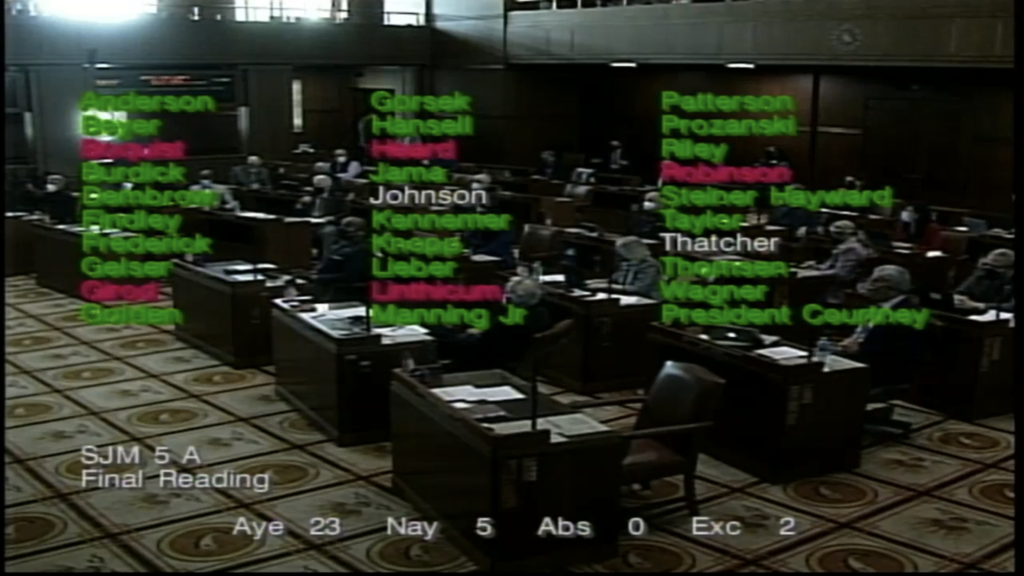

As I organized CCL volunteers across Oregon, we successfully urged over 30 Oregon legislators to endorse the EICDA by early 2021. September 17, 2020, I met by phone then Rep. Tiffiny Mitchell to ask her to endorse the EICDA. In addition to her endorsement, Tiffiny asked if she could introduce a statewide resolution supporting the bill. Because of a great rapport I had built up with Senator Michael Dembrow and his friendship with Tiffiny Mitchell, he proudly introduced the resolution on the Oregon Senate floor February 4, 2021, when it officially became known as Senate Joint Memorial 5 or SJM 5.

SJM 5 passed the Oregon Senate on April 7th by a vote of 23 to 5, with 6 Republican Senators, half of the Oregon Republican Senate caucus, joined with all the Democratic Senators present to vote to support SJM 5. Unfortunately, SJM 5 fell short of receiving a floor vote in the Oregon House in June 2021. The exciting part was that 30 House members, including 7 Republicans, signed on to co-sponsor SJM 5. The Oregon House has 60 members. Thus, half the chamber were co-sponsors of SJM 5.

More recently, as I have blogged about, I developed a good rapport with my current Oregon legislators Senator Kayse Jama and Representative Andrea Valderrama, as well as other nearby Oregon Legislators, as I have lobbied them for various climate legislation.

My favorite part of my William Gladstone Steel Ranger Lodge talk

One particular section of my Will Steel talk I hope really stuck in people’s minds. This was the central part of my Will Steel talk that deeply connected with me:

“After Will Steel saw Crater Lake for the first time, it literally changed his life. When he went back up to Portland Oregon, he started a petition drive. He got hundreds of signatures from friends, associates, and anyone he could find to start a campaign to make Crater Lake a national park. On top of that, he wrote close to a thousand letters nationwide basically every major magazine and newspaper in the country. He proclaimed that Crater Lake should be a national park.

Even more, he wrote every single member of Congress a letter trying to lobby them to make this a national park. However, none of these efforts were enough. William Gladstone Steele then had to make numerous trips to Washington DC to personally lobby senators and congressmen to make this a national park. He became such a fixture at the Capitol that senators and congressmen would duck around doors and hallways whenever they saw him.

They thought that Will Steel as a pest and a crackpot. They probably told him, ‘Will Steel, go home! Give it up! We are not going to turn your little lake into a national park!’

But Will Steel would not give up. He said, ‘I got licked so often that I learned to like it!’

After 17 years of having a force of will and a persistent determination, Congress finally gave into William Gladstone Steel to get him off their backs. In 1902, Congress passed a law to make Crater Lake into a national park. President Theodore Roosevelt signed it into law on May 22, 1902. Today Crater Lake National Park is the fifth oldest national park in the United States.

William Gladstone Steel is quite a success story. But think about it. From the first time he saw Crater Lake until it became a national park, took 17 years of his life for his dream to come true. 17 years that’s a long time. It’s about the same amount of time it takes to raise a child from when they’re born until about the time, they’re ready to graduate from high school.

17 years. So, what does that say?

- It says that one person. Any one of us here today can make a difference.

- It also says never give up on your dreams, no matter how crazy they may be.

- It also says it may take an incredible amount of persistence and determination, as well as hearing a lot of ‘no’s for your dreams to come true.”

The part of my talk that would get a big laugh from the audience was when I said that Will Steel “became such a fixture at the Capitol that senators and congressmen would duck around doors and hallways whenever they saw him.”

To emphasize this point, I pretended to duck behind a wall just for a moment during my talk acting like I was a U.S. Senator or Representative avoiding Steel at the Capitol. The audience seemed to know exactly what I was doing which made my talk even more humorous. It was one of my favorite highlights from this talk and a line that stuck in my head for how determined he was in his lobbying to urge members of Congress to make Crater Lake into a national park.

Like Will Steel, someone tried to avoid me with my climate lobbying

When I was starting to write this blog, I remarked to my wife Tanya, “At least no members of Congress or state legislators tried to duck around doors and hallways when they saw me.”

“Actually, they have,” she responded, and we both laughed. She remembered me telling the story of how Oregon Senator Laurie Monnes Anderson went out of her way to avoid me.

On June 25, 2019, I was lobbying as a Renew Oregon volunteer at the Oregon Capitol building in Salem, Oregon to urge state Senators to hold a vote to pass the Clean Energy Jobs Bill, HB 2020. The Democratic Senators had the votes to pass the bill. Unfortunately, the Republican state Senators fled the state to deny the 2/3 required quorum to hold a floor vote in the Oregon Senate. The Democratic Senators who remained at the state Capitol were unsure what to do.

Renew Oregon wanted volunteers like me to continue raining a presence inside the Capitol Building. They asked us to continue wearing our Renew Oregon t-shirts. They wanted us to be seen in the lobby of the Senate offices and in other parts of the building by the Democratic Oregon Senators. We didn’t want the Democratic Senators to give up on HB 2020. The Democratic Senators were under a lot of pressure to kill this bill so the Republican Senators would return to the Capitol, and they would have the required quorum to pass the state budget and all the remaining bills in the session. The Oregon Constitution stated that the Legislative session had to end by midnight on June 30th. Otherwise, all the bills would die. Thus, it was extremely tempting for the Democratic Senator to sacrifice HB 2020 for all their other legislative priorities.