For almost 23 years, I have been a summer seasonal park ranger at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. The biggest change I saw in the park during this time was climate change.

|

| An American Crocodile lurking in the water |

I never saw any snakes when I canoed to Snake Bight. However, the variety of wildlife I did see there was incredible. The bay is very shallow only about 2 to 4 feet deep during high tide! Thus, if you fall out of your canoe, you just stand up. Because it is so shallow, it becomes an all you can eat seafood buffet for the birds: shrimps, crabs, oysters, small fish, etc. I will never forget seeing thousands of tiny shorebirds that would take off in flight when they would be suddenly pursued by a Peregrine Falcon. They swoop in like a jet pilot to go after these clouds of birds that would suddenly turn like they were one organism.

While canoeing around that area I got to see the endangered American Crocodile while would lurk in the water like a WWII U Boat submarine with its iron grey color. They can get up to 8 to 12 feet long. However, they were always leery of the canoes and kayaks which they considered to be larger and more dominating animals.

While working as park ranger in the Everglades, I quickly learned that visitors expect rangers to know everything, don’t they?

Visitors started asking me about this global warming thing that I personally had no knowledge. Soon after I started giving ranger talks in the Everglades in 1998, I started read all I could about climate change so I could be well informed. In the summer of 1999, I went to a Florida City bookstore on my days off and bought the book, Laboratory Earth: The Planetary Gamble We Cannot Afford to Lose by climate scientist Dr. Stephen Schneider (1945-2010) of Stanford University.

|

| Park Ranger Steve Robinson |

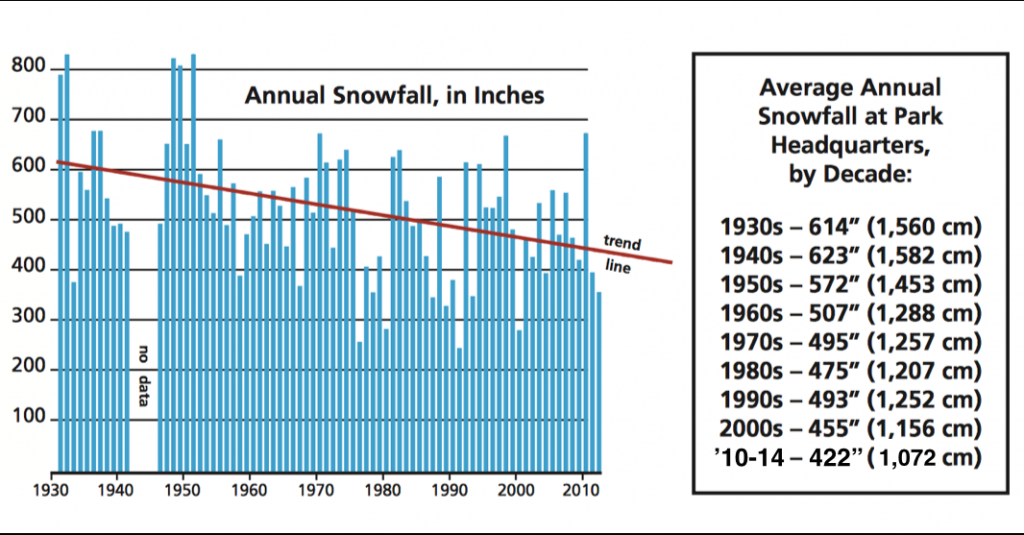

Most snow that falls in the park eventually leaves the park to nourish the rivers of southern Oregon and northern California. Less snow falling in the park means less water is leaving the park to support cities, ranches, farms, and wildlife downstream.

2. The waters of Crater Lake are getting warmer.

Scientific lake monitoring began in 1965. Since then, scientists have documented the waters of Crater Lake getting warmer. Surface temperatures in the summer have risen at an average rate of 1 degree Fahrenheit (.6 Celsius) per decade, from 54 degrees Fahrenheit (12 degrees Celsius) in a typical year in the 1960s to 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius) today. Similar increases have been seen in other North American lakes, including Lake Tahoe and Lake Superior.

It remains to be seen what impacts (if any) this increase will have on the lake’s ecology. I personally hear a researcher speculate that warming lake temperatures could spur the growth of algae, reducing the water’s clarity.

That would be very unfortunate because Crater Lake is still considered to be one of the clearest and purest bodies of water in the world. In fact, its water is cleaner than the tap water in your home. This is because roughly 83% of it comes from rain and snow falling directly on the lake’s surface, while the rest is runoff from precipitation on the caldera’s inner slopes. No rivers or creeks carry silt, sediment, or pollution into the lake.

3. Climate change puts pikas in peril.

|

| Photo by Beth Pratt-Bergstrom, California Director at National Wildlife Federation |

The American pika (Ochotona princeps) is a small mammal that inhabits rocky slopes from Canada to New Mexico. At Crater Lake, pikas are often seen harvesting wildflowers along the Garfield Peak Trail, which starts by the historic Crater Lake Lodge in Rim Village.

Rising temperatures appear to be driving some pika populations extinct. Pikas are not able to tolerate warm weather; their dense fur is not efficient at releasing heat. A few hours in the sun at temperatures as low as 78 degrees Fahrenheit (26 degrees Celsius) can be fatal. Climate change also may be altering vegetation patterns and shrinking the food supply of some populations.

Many pika populations live high up on isolated peaks. While other mammals might be able to migrate in response to climate change, most pikas cannot. At least three Oregon pika communities southeast of Crater Lake have vanished in recent decades.

Whitebark pines (Pinus albicaulis) grow on the rocky rim of Crater Lake and atop the park’s tallest peaks. They are considered a “keystone” species, since so many other species depend on them for food, shelter, and survival. Unfortunately, half the park’s whitebark pines are currently dead or dying.

Tiny mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae), rarely seen, is responsible for much of the damage. Scientists think, however, that the real culprit may be climate change. For millennia, mountain pine beetles have thrived in the forests of western North America. In the past, however, their intolerance of cold weather generally safeguarded high-elevation trees. Lower elevation trees, such as lodgepole pines and ponderosa pines, were the beetles’ main targets.

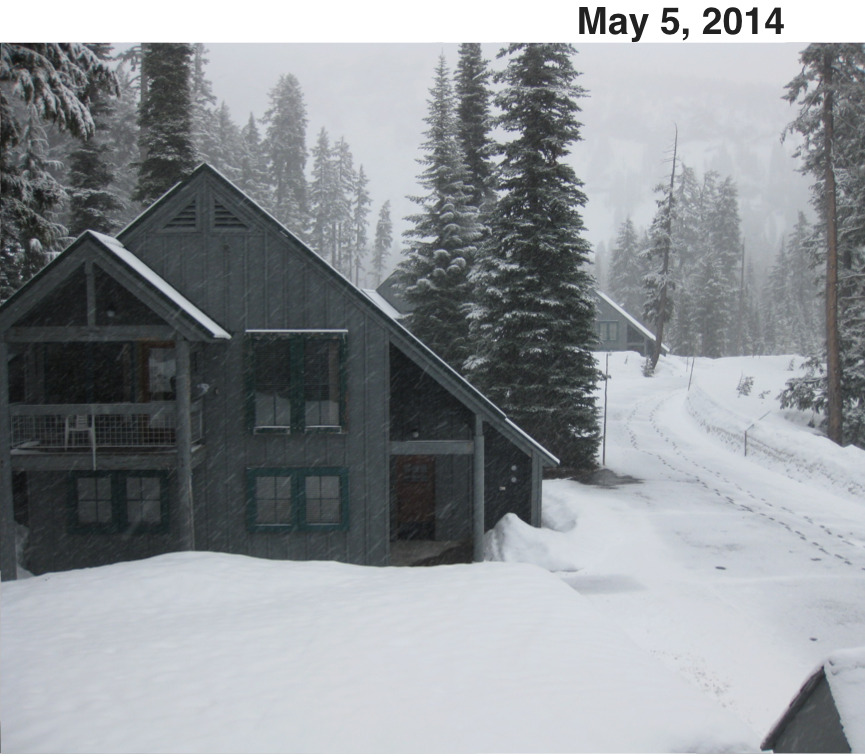

My first time seeing Crater Lake with my own eyes was May 20, 1992, just 3 days after my college graduation ceremony from William Jewell College, in Liberty, MO. I was amazed how much snow there was on the ground, about 5 to 6 feet, when I arrived to work there for the first time. I love cold weather and seeing snow falling. Because of the high elevation, it was amazing for me to see that snow could fall anytime of year at Crater Lake. This was a welcome relief for me since I grew up hating the very hot and humid summers in my hometown of St. Louis, MO.

At Crater Lake, I always loved seeing snow falling throughout May, the first three weeks of June, and in the autumn months of September and October. However, I am now noticing that it is raining more and snowing less in May, June, September, and October.

One of the advantages for me of working in the same park so many years was that I was able to arrive early in the summer season, typically around the beginning or mid May. Even more, I was assigned to the same park housing unit for the past three years in a row.

However, when I arrived at Crater Lake on May 5, 2014, there was only about 3.5 feet of snow on the ground. I was shocked at how little snow I saw. It was half of the normal snow depth 7 to 8 feet of snow that I had seen in past years around this time. It felt like I had arrived at Crater Lake in June, not May!

|

| Brian Kahn Image Source: Climatecentral.org |

For the second winter in a row, Crater Lake is not alone in the western United States for extremely low snow accumulation. According to Brian Kahn, science writer for Climatecentral.org, California Ski resorts such as Mt. Shasta Ski Park, Badger Pass and Mt. High are closed until the next storm dumps enough snow for skiing. Kahn then writes that “the snow drought extends north into Oregon and Washington. In the Olympic Peninsula located west of Seattle, only 3 percent of its average snow-water equivalent has fallen this winter — an important snow metric for water managers.”

I show my audience that Crater Lake is doing what it can to reduce its carbon emissions with trolley tours, hybrid and electric staff vehicles, and solar panels installed by our Mazama Camper store and our North Entrance station. I acknowledge that is not nearly enough for Crater Lake to seriously reduce our carbon emissions. Thus, I challenge my audience to get involved.

|

| Brian Ettling Presenting at Grand Canyon National Park May, 2013 |

On the other hand, seeing the hundreds of park visitors positively respond to my climate change evening program has wonderful experience for me. Since presenting this talk numerous times since 2011, I had a paper published about my talk in Yale Climate Connections in April, 2012. I was invited to give this talk as a guest speaker at Grand Canyon National Park in May, 2013. National Journal writer Claire Foran wrote an article about my efforts communicating with park visitors about climate change in the December 2014, Next Time You Visit a National Park, You Might Get a Lecture on Climate Change.