“Don’t hold your breath at seeing Denali. It’s probably not going to happen. Professional photographers wait days, if not weeks, to get that perfect picture of the mountain that you see on postcards.”

This was the friendly advice of local Alaskans when my parents, younger sister and I traveled to Alaska during a three week vacation in July 1988. When we started our trip in Fairbanks, we struck up conversations with local Alaskans while we visited for a couple of days. Our family is outgoing and gregarious. We loved chatting with strangers when we were on vacation. In turn, the resident Alaskans were curious about our family. They inquired where we were from in the lower 48 states and what we hoped to see in Alaska.

For anyone conversing with us, my parents shared the full trip itinerary that they had a Lutheran Marriage Encounter Convention to go to in Anchorage. Thus, they hired a travel agent to assemble this trip to fly to Fairbanks, take the Alaskan Railroad south, stopping in Denali National Park for a couple of days, then reaching our destination of Anchorage to stay with friends and attend the convention. With the locals, I got straight to the point. I hoped to see Mt. McKinley in Denali National Park or on the train ride down to Fairbanks. They rolled their eyes because most visitors they encountered really wanted to see the mountain. Their typical response:

‘Good luck! The mountain is typically shrouded behind clouds. People living in areas with views of it can go for weeks without seeing it. Don’t get your hopes up high. Most visitors don’t get to see it, except for the images they take home on the postcards they buy.’

I sensed an ingrained skepticism with Alaskan residents thinking that tourists like me would not have a visible view of the mountain, nor should we expect to see a view just because we traveled far to see Alaska. My stomach churned as they cautioned me that my odds were low in seeing the mountain. I appreciated their honest sincerity, but I hoped they were wrong.

The Prominence of Denali or Mt. McKinley?

Denali is on my mind these days because President Donald Trump. When he became President on January 20, 2025, Trump proclaimed in his Inaugural speech that the name of mountain Denali would be changed back to Mt. McKinley. He did this in response to President Barak Obama endorsing his Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell to change the name from Mt. McKinley to Denali in 2015. Denali means “the high one” or “The great one” by the Native Alaskan people known as the Koyukon Athabascans. Ironically, President William McKinley never saw it when it was named after him in 1896. He had no significant historical connection to the mountain or to Alaska. I doubt Donald Trump has ever seen the mountain. If he did, he would understand why most Alaskans call it Denali. I saw it. It made a huge impression on my life.

Prompted by the passage of a resolution by the Alaskan Legislature in 1975, Governor Jay S. Hammond formally requested the Secretary of the Interior direct the U.S. Board of Geographic Names to change the name to Denali. For many decades, Denali was still the common name used in the state and was traditional among Alaska Native peoples. Thus, I will use the name Denali to refer to the mountain for the rest of this writing, in deference to the people of Alaska.

Denali deserves respect for its massive size. According to Alaska.org, “From its base to its summit, Denali rises about 18,000 feet, about one third more total height than the same measurement for the world’s tallest peak, Mount Everest. That makes Denali the tallest mountain in the world—measured from base to peak—that’s wholly above sea level.”

Talking my parents and younger sister into visiting Alaska

Growing up in St. Louis, Missouri in the 1970s and 1980s, I dreamed of seeing the snowcapped mountains in the western United States. Missouri has no towering jagged snowy mountains, just the rolling hilly mountains of the Ozarks.

While in high school, I decorated my bedroom wall with a poster of Mt. Shuksan, located in North Cascades National Park, Washington. When I hung the poster, I had no idea of the name of that mountain or where it was based. I endlessly stared at this poster of a broad sided craggy mountain with several glaciers resting on it and pockets of snow clinging to it. I knew I wanted to see mountains like this someday when I had an opportunity.

My parents participated in an organization called Lutheran Marriage Encounter when I was growing up. They first went on a weekend marriage encounter retreat in 1975. They enjoyed attending the annual national and international conventions that took place over the years in various locations such as Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Dallas, Denver, St. Louis, etc. In early 1988, I overheard them saying that the 1988 Marriage Encounter Convention would happen that July in Anchorage, Alaska. I immediately asked them if all of us could go to Alaska on a family vacation while they thought about traveling there to attend this convention.

My parents love to travel like I do. They were immediately sold on the idea. I graduated high school in May 1987. I was on a gap year getting ready to start college at the end of August 1988. During that year, I worked as a cashier at a nearby gas station to save up some spending money for college. I used some of my earnings to go on trips, such as with a friend to see Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in February 1988. In September 1987, my mom went along with me on an Amtrak train trip from St. Louis to see New York City to Boston and back. After the Pittsburgh trip, I was eager for my next big trip.

As soon as my parents mentioned Alaska as a summer destination for them, I knew I wanted to go there. I figured it would be the perfect family vacation. I will always appreciate that they quickly agreed with me that we should go there as a family. My older sister Lisa lived on her own in St. Louis and was no longer interested in joining family vacations. My younger sister, Mary Frances, was a junior in high school, still living at home. She seemed fine with the idea of traveling to Alaska with us.

God bless them! My parents welcomed my ideas in planning this trip. My dad was a passenger and freight train fanatic. I suggested that we take an Amtrak train from St. Louis to Seattle, Washington and then fly to Alaska. On the return flight from Alaska, we would take Amtrak from Seattle back to St. Louis. My parents liked that idea. If we went to Alaska, I thought we should really see Alaska. Not some puny trip to Anchorage.

With my dad’s passion for trains, we agreed we should fly to Fairbanks and then take the Alaskan Railroad down to Anchorage, stopping at Denali National Park for a couple of days in-between. This was 1988 before the internet, when travel agents exclusively organized trips like this. My parents went to the travel agent in the strip mall near our home. She did her magic to put together an itinerary for everything we had in mind and even for things we had not thought about. She suggested a rafting trip on the Nenana River near Denali National Park.

The idea of travel agents now sounds about as quaint now as rotary phones, fax machines, television reception using rabbit ear antennas, smoking in restaurants and airplanes, corner pay phones, Blockbuster Video renting movies on VCR tapes, etc. But that’s the world I remember in the 1980s. The travel agent’s office was a world of its own. Inviting posters on the wall of Florida beach scenes with palm trees, European Castles, and cruise ships floating near tall Alaskan glaciers. There were no booking airline tickets, hotel reservations, car rentals, and outback excursions at home back then. One was at the mercy of their local friendly travel agent. Fortunately, this travel agent pieced together a fabulous trip to Alaska for our family in July 1988.

The getting ready for journey to Alaska and the cross-country train trip

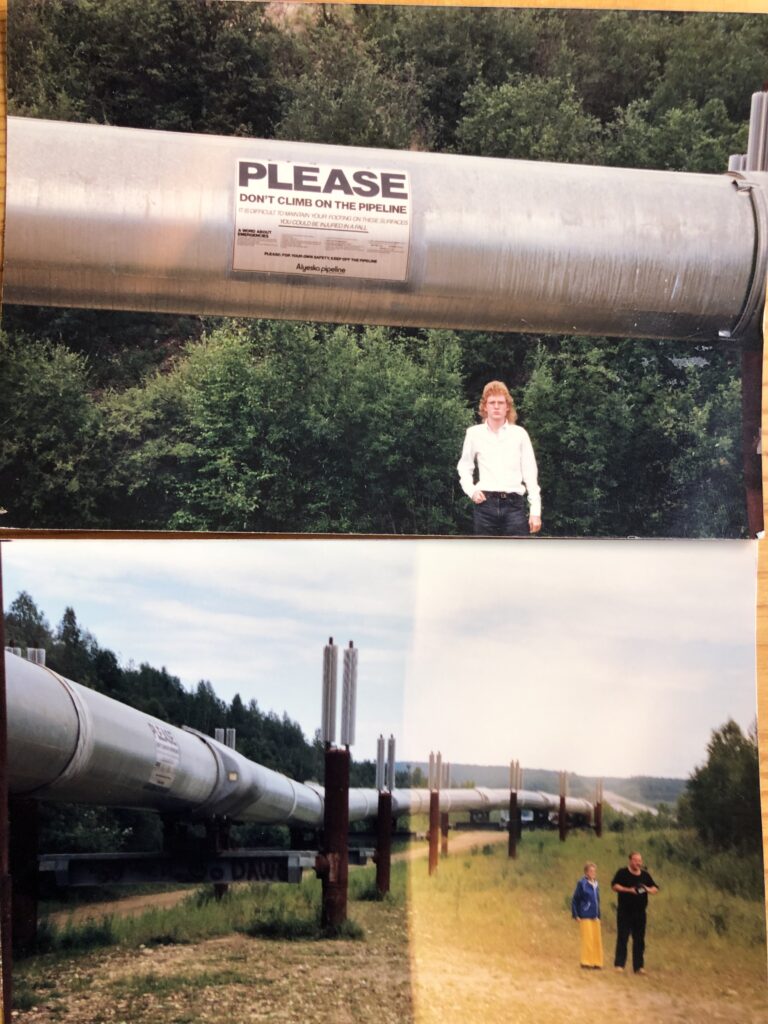

I knew this might be the only time I seeing Alaska, so I bought a new camera. I purchased a Pentax K1000 35 mm film camera. Digital cameras did not exist then. If one wanted to take photos, you had to put a spool of film in the camera which shot a maximum of 24 or 36 photos. If you were lucky, the extra amount of film at the beginning or end of the roll might allow you to snap an extra photo or two. The key was not exposing the end of the film roll to light when installing it or taking it out of the camera. Hence, the half overexposed photo of the Alaskan Pipeline you will see scrolling down this blog.

My best friend Scott and his dad Ty recommended the Pentax K1000 camera. I admired both for their photography skills. In addition, I purchased a 100 to 200 mm zoom lens that was compatible for this camera. I figured the zoom lens gave me a better opportunity to photograph distant mountains or wildlife that I might see in Alaska. Scott and Ty thought I made a good choice with the zoom lens to try to get quality photos from this trip.

Unfortunately, I only shot about one roll of film before this trip. I took photos of downtown St. Louis and from Bee Tree Park near my parents’ home. This local park had picturesque cliff views of the Mississippi River. The photos turned out crisp and clear from my practice photos. Unfortunately, I did not spend enough time learning the shutter speeds to take superb photos. Most of my photos from that Alaska vacation were blurry since the shutter speeds I used were too slow. It was a crushing blow when the developed photos were ready to be picked up at my neighborhood Walgreens. Looking back now, I still captured some good memorable photos from the trip. However, it’s the memories of that fantastic trip that sustains me to this day.

We started the trip with an Amtrak train from St. Louis to Chicago, Illinois. My parents were perpetually late for nearly everything growing up. I remember it was a stressful experience barely catching this train on time. I was internally furious at them for making it such a close call that could have ruined the entire trip. At the same time, I was so relieved we made the train before it left the station, and we were successfully on our way!

From our connection in Chicago, we started heading west on Amtrak. We had sunny skies in Denver, Colorado. We had lovely views of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. It made me eager to imagine how much higher the mountains might be in Alaska.

In Salt Lake City, Utah, our train split up. One train engine pushed half the cars to San Francisco, on a train route known as the California Zephyr. A different locomotive engine pushed our passenger cars with a destination of Portland, Oregon. We traveled on a train route named The Pioneer. It was my first time seeing Oregon. One of the highlights of this cross-country train route was traveling through the Columbia River Gorge.

The Gorge was impressive with towering hills and mountains on either side as the wide Columbia River straddled the Oregon and Washington border. I distinctly remember getting a quick peak of the 12,000-foot-high Mt. Adams as the train rode west of Hood River. My wife Tanya and I moved to Portland, OR in 2017. I feel nostalgia for that first train ride now when we drive through Hood River on I-84. This freeway goes along the same route through the Gorge as The Pioneer did, and I get that same fast glimpse of Mt. Adams that I saw from the train in 1988.

That train ride through the Gorge gave me a yearning to see more of Oregon. It motivated me four years later in 1992 to take a seasonal job at Crater Lake National Park in southern Oregon so I could see more of the state. Sadly, The Pioneer Amtrak route was discontinued in 1997. However, current efforts are trying to enable Amtrak to bring back that train route.

The train made a stop in Portland that allowed us to stretch our legs on the train platform before we rode onto Seattle, Washington. From Seattle, we caught our plane to Fairbanks, Alaska. The plane ride was not memorable except my younger sister sat near a smoker. Mary Frances did not like to be around cigarette smoke. She claimed she was allergic to it. My sister and mom asked the flight attendant if the passenger could stop smoking since it caused problems for them. The passenger did not care and he smoked even more cigarettes. Thank goodness the rules changed years later, and one cannot smoke on commercial flights anymore.

Having a quirky time in Fairbanks

We arrived in Fairbanks late in the afternoon. The airport looked geared for a small town dumped in the middle of nowhere. We rented a car to explore Fairbanks for a during our two night and one full day visit. We ate a delicious Alaska salmon dinner at an outdoor local establishment with picnic tables along the small Chena River. The fish was cooked on open flame barbeque pits. It was some of the best tasting fish of my life. This area was called Pioneer Park. It had old western style store fronts and homes, commemorating early Alaskan pioneer and gold rush history. The food was so tasty that we went back for a second night for dinner.

After dinner on the first day, we stopped by a grocery store to get some items. A store clerk named James who was about a couple years old than my sister struck up a conversation with her. My sister was impressed that he was friendly, kind, easy-going, attractive, and he wanted to get to know her. He asked her out on a date for the next evening. She was thrilled for a chance to go out on a date with a local Fairbanks young man. She asked my parents if it was ok to go out the next evening and my parents were fine with it. We all thought it was funny that my sister caught the attention of a local resident.

On our arrival day in Fairbanks, we were amazed it was still daylight at 10:30 pm. My dad and I took a drive to see the famous Trans-Alaska pipeline. It is 800-mile-long oil pipeline. It runs from Prudhoe Bay on the northern edge of Alaska to the town of Valdez in southern coastal Alaska. At the Valdez Marine Terminal, oil is loaded onto tankers for shipment to global markets. Construction of the pipeline took three years from April, 1974 and finished in June, 1977.

I remember seeing the Alaskan Pipeline on the TV news as a child. It seemed to be a big deal for American ingenuity at the time. Plus, the U.S. staggered with ongoing oil crises in the 1970s. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) boycotted American markets in 1973-74, plus gasoline price spikes due to inflation. The pipeline seemed to be an answer to American oil production woes. According to the ConocoPhillips website, this pipeline was “the world’s largest privately funded construction project when it was built, at a cost of $8 billion.”

In its own way, the pipeline was an iconic engineering marvel. It set a standard for design which endures to this day. Its distinctive zig-zag looks allow the pipe to flex in the event of an earthquake. More than half the pipeline runs above ground, cradled by metal supports, so the hot oil does not melt the permafrost that is prevalent along the route. I vaguely remember as a child that it was controversial with environmental protesters trying to stop it. With all the effort to construct this pipeline, keep the oil flowing, heat the oil so that it does not freeze in the frigid Alaskan winters, and maintain the pipeline, I wonder now if it would be cheaper to switch to clean energy. Just a thought.

My dad and I noticed how quiet it was by the pipeline since we outside the developed area of Fairbanks. It was silently doing its job, without any protesters or signs of workers fiddling with it, at this spot. We were curious to see the Alaskan Pipeline since it made so much news when it was completed in 1977. With its meandering design stretching out to the horizon, it seemed like America’s modern answer to the Great Wall of China. Even more, my dad and I appreciated that we could look at it at 10:30 pm with plenty of daytime on this long July Alaskan day.

We then went to the local grocery store to see people shopping. It was busy like it was 5 pm, rather than almost 11 pm. We laughed as I remarked to my dad, “Don’t these people ever sleep?”

The next day, we explored a museum in Fairbanks where they were constructing a totem pole outside. We went to a shopping mall where they had adult Bengal Tigers and one cub in tiny cages that looked like jail cells. We wondered: What did these tigers do wrong? One tiger in the cage was trying to sleep off the experience in this brightly lit mall. Another tiger just paced back and forth in the cage that was way too small. Even more oddly, they had a bamboo booth set up to get photos with the with the Tiger cub.

That evening, Mary Frances went on the date with James. It was after 10:30 pm. My sister was not back at our hotel room. My mom sat on a bed worried. My dad anxiously paced the small hotel room, like the tiger in the cage that was too tiny we observed earlier that day. He exclaimed, “I should not have let her go out on this date, especially to stay out this late!”

I sarcastically replied, “Gee, Dad, you should not have told her that it was ok to stay out until it got dark!”

Fortunately, they laughed at my joke. It broke up the tension in the confined hotel room.

A few minutes later, my sister strolled in the room. Mary Frances said she had a lovely evening with him. James asked her about our vacation plans. She told him that we would be in Anchorage later that week. He indicated he would drive from Fairbanks to Anchorage when we there to meet up with her. We thought that was funny Fairbanks to Anchorage is about 360 miles apart or a 6-and-a-half-hour drive without stopping. My sister thought it was flattering and endearing. At the same time, my sister thought there was zero chances of seriously dating this guy. First, he lives in Alaska, and she lives in Missouri. Talk about a long-distance relationship! Second, she was still a teenager in high school not really interested in seriously dating anyone yet.

When we were in Anchorage later this trip, James showed up driving all the way from Fairbanks hoping to spend time with her. My sister, my parents, and I all thought it was amusing and odd. Mary Frances met up with him again. However, that was a very long drive to find out she was not going to be his girlfriend.

Exploring Denali National Park

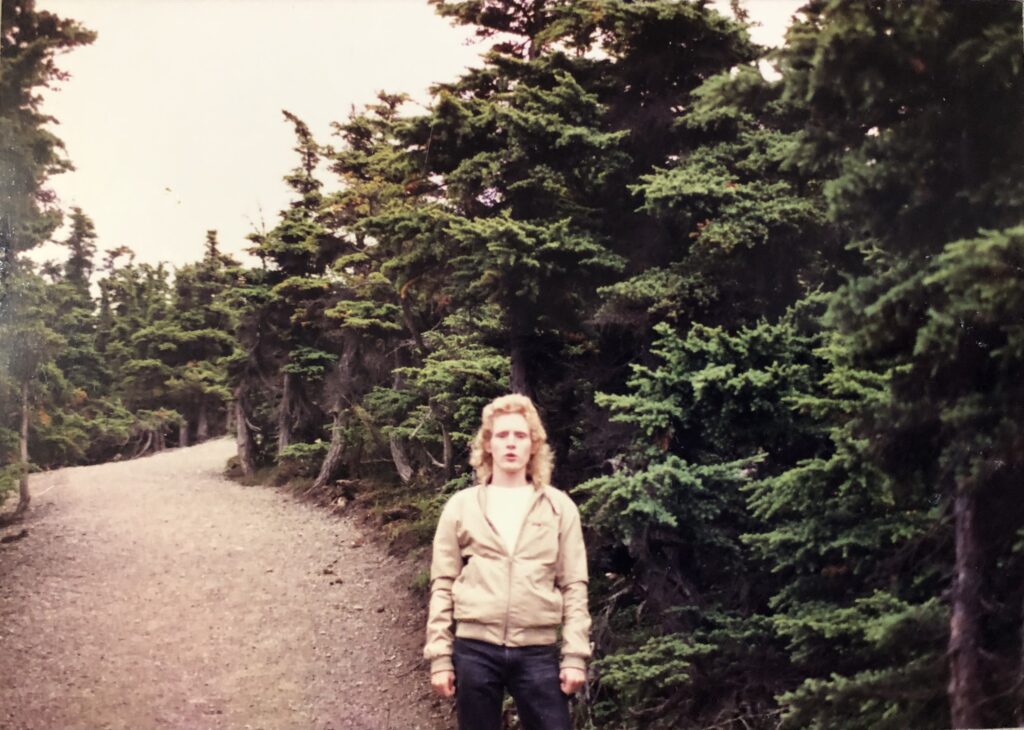

The next day, we boarded the train in Fairbanks to head to Denali National Park. I was amazed how sparse civilization was and no sightings of people from Fairbanks to Denali. The pine trees stretched for miles, but they all looked stunted and puny. They had an enchanting deep green color. However, a tall tree in an Alaska only seemed to stand about 5 to 7 feet tall.

We arrived at the train station in Denali. We then traveled the main park road in the park the only way one could: with a group of fellow tourists on packed board an old school bus. We had a naturalist guide narrating the tour while driving the bus. He had a long deep brown hair and beard. He looked like a cross between Jesus and someone who had spent years living as one with the Alaskan wilderness. He was a terrific storyteller. He may have influenced me more than he or I ever knew. Just over 10 years later in the Everglades, I would be narrating tours there while having a very long hair and beard.

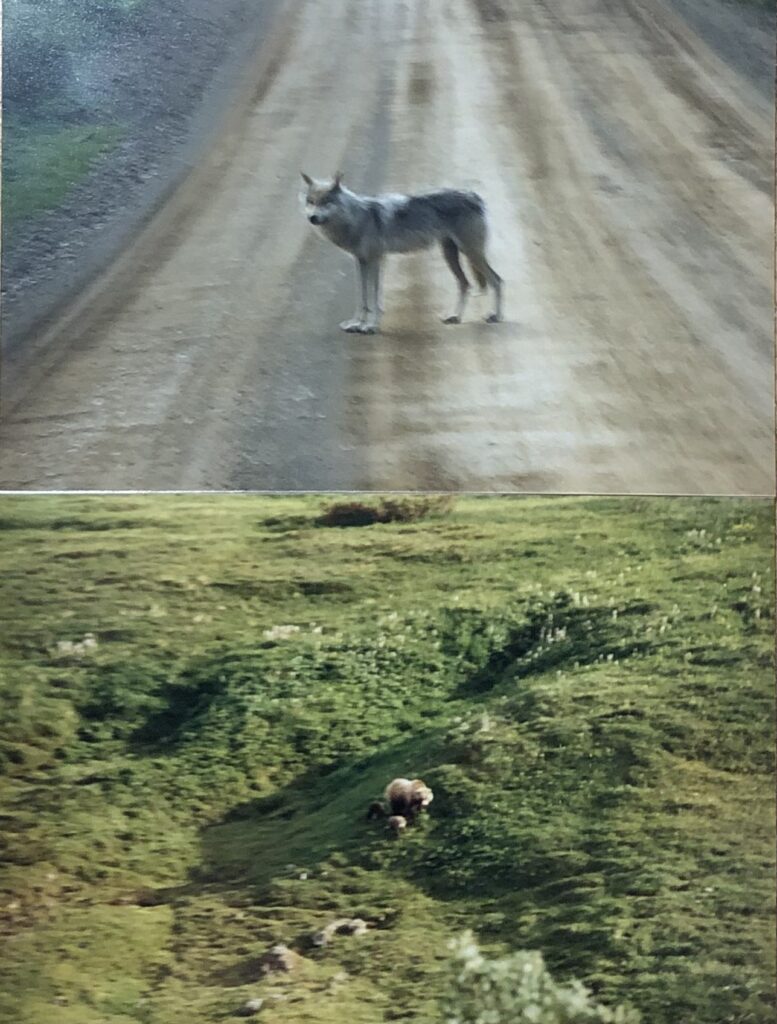

This naturalist did a fabulous job at pointing out the wildlife and slowing down the bus so passengers on both sides could see the animals. We had a wolf strolling down the road alongside the bus for a several yards. A distant moose grazed within a low patch of trees watching us as we observed her. We then spotted a grizzly bear mother and two cubs in a grassy plain a couple hundred yards from us.

Our naturalist guide drove us to the end of the road where Denali would greet us on a clear day. However, it was an overcast day with the tops of all the nearby mountains shrouded. I started to believe that the resident Alaskans were correct: It is nearly impossible to see Denali when you are in Alaska. I crossed my fingers I might have better luck later this trip.

The next day we went rafting on the Nenana River. My parents, sister, and I loved the rafting trip. It was the first time we had ever seen a Bald Eagle. It glared down at us from a tree not far from the raft. The water was calm and relaxing. The color of the water was gray, opaque, and chalky. This was my first time seeing a glacier fed river and it fascinated me. This was not a white water or white-knuckle rafting trip. I recall the rafting trip as serene, relaxing, and mellow.

The rafting guide advised us to not go swimming since the temperature of the water from being a glacier fed river was only a few degrees above freezing. He warned that we could get hypothermia fast since the water was so cold. The murky color of the water and the sudden knowledge of the frigid water temperature canceled any temptation for us to go swimming.

Our guide was young, just a few years older than me. I turned 20 years old during the trip. He liked his job and told many funny jokes. The way he enjoyed his job made me wonder if I should look for recreational jobs in the outdoors or a national park. I was not interested in a rafting job, but I was intrigued to work someday in a scenic area leading narrated tours.

Like the previous day, it was overcast with no mountain peaks in sight. The Denali National Park naturalist guide from the day before and the rafting guide that day affirmed that is very unlikely to see Denali since it is covered in clouds most of the time. I still hoped that all the Alaskans I encountered about this would be wrong.

After the rafting tour, we ate dinner at Grande Denali Lodge. As my mom, sister, and I waited outside for my dad who was in the restroom, we saw hordes of people getting off and on buses and even the train. Most of them were senior citizens. One of them even farted and did a weird dance afterwards to shake it off. My mom made a joke that for now on when she saw crowds of seniors, she would start referring to them as The Alaskan Crowd.

Denali can’t hide itself forever, or can it?

The next day we boarded the train to start heading south to Anchorage. The train trip would take several hours to reach Anchorage, if not most of the day. The train would spend a great deal of time traversing around the east edge of Denali National Park. It was another overcast Alaskan day. It appeared doubtful I would see the mountain. The Alaskans I met were not with me on this train, but they would have laughed at me straining my eyes looking out the train window to get any kind of sight of Denali.

Then it happened an hour into the train trip. The clouds parted! The mountain was out! We had a blue sky with a few small clouds in front of Denali, but not enough to block the view of it.

Denali was a huge glistening white marvel of nature, rising twice as high as the mountains in front of it. I never saw anything more gigantic in my life. Most iconic mountains such as Mt. Hood, the Matterhorn, Mt. Fuji, the Grand Tetons, etc. look more like they rise to a very fine pointy church steeple top. Not Denali. It looked like a mammoth wall of rock, snow, and ice. It gave the impression that it was a lofty Himalayan Mountain that got lost and ended up in the middle of Alaska all lonesome by itself.

I could not stop taking photos of it. I remember my Dad was ecstatic to see the mountain like me. Fortunately, I used a fast enough shutter speed on my camera to get decent photos of the mountain. The local Alaskan experts were wrong! I could actually see the mountain!

I was glad the Alaskans warned me that I would probably not see Denali. It made the experience of glimpsing the mountain on the train that much sweeter. The train was beneficial because as it went along the curves, we got various looks of the iconic peak, revealing an enormous size from different angles. It finally got to the point where I could only see Denali from the back of the train. Even more, the clouds were moving back in to obscure the mountain again.

It was as if Mother Nature and Denali said to me, “Yeah. I will give you one quick view of the mountain, but that’s it!”

Seeing Portage Glacier just outside of Anchorage, Alaska

Obviously, seeing Denali was the highlight of the trip. The rest of the Alaskan trip was fun after we arrived in Anchorage. We liked exploring the Anchorage Museum showcasing Alaskan history, art, culture, and science. My favorite artwork was large landscape painting of an Alaskan wilderness scene. A rushing river flowed through it with tall hills with dark trees on both sides of the river. A majestic view of Denali dominated the background. The painting signaled to me how Alaskans revere this mountain. The artist who painted it showcased the beauty of the mysterious highest point in North America that many visitors travel a long way but fail to see. The painting seemed to say, ‘Behold this sacred mountain that is tough to get a view!’

In the central large open space of the Anchorage Museum, we watched two folk dancers perform traditional Slavic and Russian dance moves. They looked to be in their 70s with their whitish hair and appearance. Yet, they performed their dance moves with a rigid precision. They both looked to be barely over 5 feet tall as they danced to the Eastern European folk music. With their small size, they looked like figurines for a wedding cake. They were probably Anchorage residents. Their clean well maintained Slavic outfits showed that they took the music, dancing, and clothes seriously while sharing their love for it with the museum patrons.

We then walked to the Anchorage Mall and noticed the ice-skating rink used by several locals in mid-July. This fascinated our family coming all the way from Missouri to see Alaskans ice-skating in the middle of summer. We were tempted to join them, but no one in our family, especially me, felt brave enough to ice skate that day.

The Sugar family attending the Marriage Encounter Convention hosted us for several days. The family was Al, Joyce, and their daughter Amy, who was around my age. The Sugars took us to see the sights of Anchorage, such as the Portage Glacier, in their family recreational vehicle (RV). I never saw glacial ice up close before. With Amy’s help, I even held some in my hands. I felt grateful to photograph this glacier July 1988.

In 2008, twenty years later, I decided to be a climate change organizer. I heard stories since then how Portage Glacier retreated due to climate change. One story was from a fellow climate advocate and friend, Larry Lazar. He was my best man when I married my wife Tanya on November 1, 2015. Yale Climate Connections published Larry’s story in January 2015. He went to Alaska on a family vacation in June 2008. But they “couldn’t see the glacier anywhere.”

Larry read a sign at the Visitor Center how the glacier retreated due to climate change. The sign had a profound impact on him. Up to that point, he did not accept the reality of climate change. When he returned to St. Louis from his 2008 Alaskan trip, he started reading the science on climate change. This led to Larry attending the 2011 Climate Change Exhibit at the St. Louis Science Center, where I worked at that time. Larry and I became friends. We co-created the St. Louis Climate Reality Meet Up in October 2011. Today it is known as Climate Meetup-St. Louis.

Larry and I became Climate Reality Leaders in August 2012. We gave joint Climate Reality climate change presentations from December 2012 until Tanya and I moved to Portland, Oregon in February 2017. Larry regularly told his 2008 Portage Glacier story in our joint talks and media interviews. While I totally accepted the science of climate change and saw the negative impacts while working in the national parks, I did not want to fully grip Larry’s story of not seeing Portage Glacier when I heard him share it from 2011 to 2017. We were strangely connected seeing Portage Glacier 20 years apart: 1988 for me and 2008 for Larry.

I selfishly want to remember it today how I saw it when Al Sugar and his family took my parents, younger sister, and I to see it in July 1988. It was a delightful day in Alaska that I was glad to experience. I would probably feel sick to my stomach to see photos of the retreat of the Portage Glacier now compared to when I saw it in 1988, almost 40 years ago.

The final days of our trip visiting Anchorage, Alaska

On the way back from the glacier, we saw a female Dall Sheep with a small lamb following not far behind her. Al Sugar climbed to the roof of RV to get a better view of the sheep. He generously offered to use my camera with the zoom lens on the RV roof to get some photos of the Dall Sheep for me. I still recall the lump in my throat as I handed him my new camera and lens as he hung over the side of the RV requesting that I hand my camera to him. I really didn’t want him to drop my camera since I bought it so recently.

I asked him if he understood how to operate my camera, since I barely knew how to use it. Al assured me that he did. He got some decent photos of the female Dall Sheep and her lamb that I would not have been able to get otherwise.

It was good to see these sights in Anchorage because I never saw Denali again after gazing at it on the train. Al Sugar told me that on a clear day Denali is easily spotted from Anchorage. The mountain is located about 130 miles north of the city — “about 130 miles away as the raven flies.” However, the weather was overcast over the entire time we were there. It only seemed like a pipe dream for me to see the mountain from Anchorage.

I celebrated my 20th birthday in Alaska. We spent the day at the Alaska Zoo in Anchorage. Similar to the Fairbanks shopping mall, I observed animals in cages looking bored or confined. I saw the polar bear close up behind the zoo bars. It looked it like had a sense of humor because it turned around with its backside to us and started peeing. Maybe it was just relieving itself. Or, sending a message that it didn’t like the tourists, including us.

As the visit to Alaska closed, we went up to Far North Bicentennial Park which had an overlook to get a bird’s eye view of the Anchorage skyline and city limits.

Then it was time leave to Alaska and fly back home to the lower 48 states. We had clear skies from Anchorage to Seattle with a chance to see lots of coastal snowy mountains from Alaska to British Columbia and down to Washington state. I got glimpses from my airplane window seat of Mt. Baker, Mt. Rainier, and an aerial view of downtown Seattle.

We then had an amazing train ride on the Amtrak Empire Builder, which travels from Seattle to Chicago. The train left the station with clear views of the Seattle Space Needle and Mt. Baker heading north before then heading east. We had great views going along the edge of Glacier National Park, Montana. The train stopped long enough in Bismarck, North Dakota for passengers to step outside and stretch their legs. Even if it was for a few minutes, it was a thrill for our family to claim stepping our feet in a new state for us, North Dakota. The train went on through Minneapolis and then back to Chicago. We then caught another train back to St. Louis.

I am grateful for my parents and Mary Frances for their openness to take this trip to Alaska.

Final Thoughts

St. Louis looked drab after returning home from Alaska and riding a train to see the northwestern U.S. states of Oregon and Washington. While in Alaska, I bought a poster of Denali which I hung on my dorm wall when I started William Jewell College in Kansas City, MO at the end of August 1988. For months afterwards, I chatted about that Alaska trip with friends, family, my college classmates, my roommate, and anyone starting a conversation with me. I took a Communications 100 Class that fall. One of my first speeches was about my trip to Alaska.

It was too remote for me to return to Alaska. But I yearned to return to the Pacific Northwest. I wanted to stare at snowcapped mountains and live close to them. I graduated from William Jewell College on May 17, 1992. That evening, I boarded an Amtrak Train for a cross-country train ride to Los Angeles, California. I then transferred to another train which took me to Klamath Falls, Oregon. The last morning of my train ride, I awoke with the metal wheels squealing as the train navigated the sharp curve to skirt the edge of the 14,000-foot Mt. Shasta in northern California. While not as tall and enormous as Denali, this mountain looked huge. Like Denali, Shasta heralded me on this clear morning as a towering mountain with its fresh winter snowpack still clinging to it. Mt Shasta greeted me with a friendly, “Welcome to the Pacific Northwest!”

At Klamath Falls, a gift store employee at Crater Lake National Park named Kevin picked me up at the train station. I spent the summer working in the gift shop at Crater Lake. I could not get enough absorbing the beauty of the snowy peaks that ringed the deep blue cobalt lake. More big mountains covered with snow stood on the horizon outside the park, such as Mt. Shasta.

I ended up working 25 years as a seasonal park ranger at Crater Lake National Park and Everglades National Park, Florida. While working in the national parks, I saw climate change negatively impacted those national treasures. It triggered my passion to organize for climate action.

Denali looms large in Alaska and in my memories. It is massive in size. It had a huge impact in my life to move to the Pacific Northwest to be near snow covered mountains. It played a role in my lifelong love of nature and an inspiration for me to be an advocate to care for our planet. May this sacred mountain inspire you, as it did for me.