“A man or woman could hardly ask for a better way to make a living

than as a seasonal ranger for the National Park Service.”

– American environmentalist author Edward Abbey from his 1973 book Cactus Country

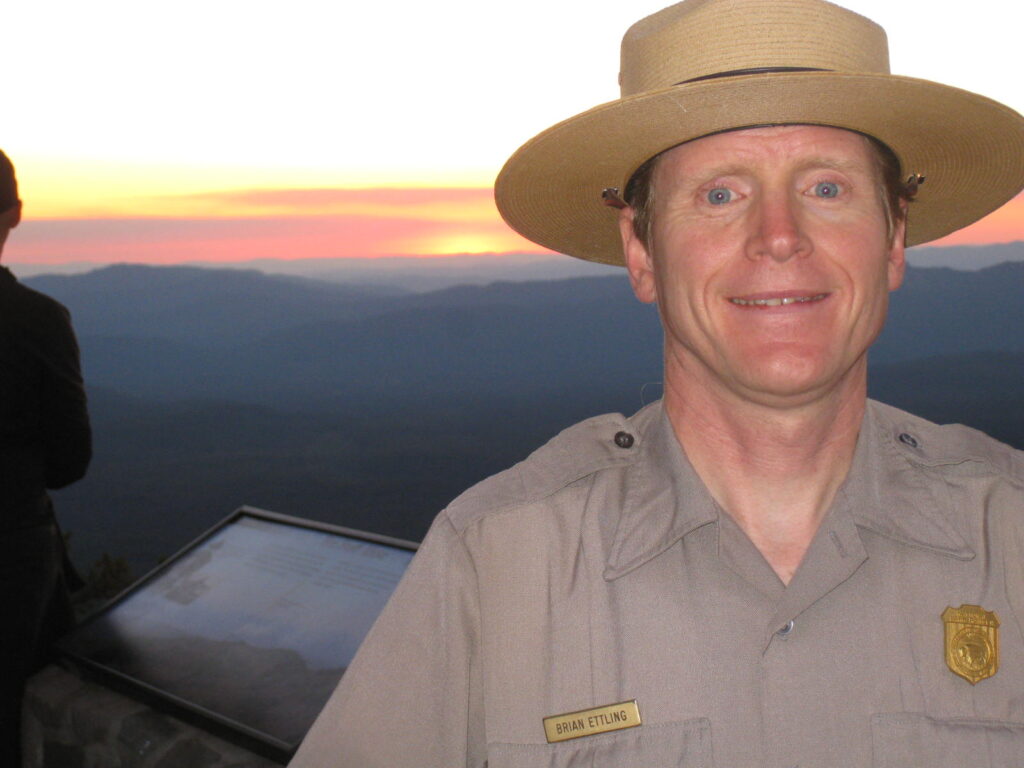

From 1996 to 2017, I proudly worked as a seasonal park ranger in the national parks. When I write about my life, I mostly simplify to say that I worked as a park ranger at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon and Everglades National Park, Florida from 1992 to 2017.

Upon graduating from William Jewell College with a Business Administration degree in 1992, I knew that I did not want to office cubical or for a large corporation in my work career. The idea of making money just to make money just never appealed to me. My desire was to get the most out of life, see as much of the world as I could, while living in beautiful and scenic locations.

My first seasonal summer jobs working at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon 1992-2005

I arrived at Crater Lake National Park on May 20, 1992, to work in the Rim Village gift store for the summer. With the deep cobalt blue color of the lake and the glistening snowcapped mountains surrounding it, I felt like I found my new home. I enjoyed hiking up the mountain peak trails to get a bird’s eye view of the area and the satisfaction of the exercise it took to reach the mountain summits. I loved how quiet the park was during the day, except for an occasional airplane flying overhead. You could hear the wind whispering through the trees. The sunsets over the lower western Cascade Mountains on a clear night were not to be missed. The sky over Crater Lake were so dark on a moonless night that I had never seen the Milky way as clear or so many stars in the sky.

I loved my summers at Crater Lake. I spent the summers of 1992-94 working in the Crater Lake gift store. The General Manager of the Crater Lake concessionaire talked me into working the night auditor position at the rehabilitated Crater Lake Lodge during the grand re-opening summer of 1995. I quickly discovered that working graveyard shifts was not my cup of tea. I was sleeping during the daytime beauty of Crater Lake.

In 1996, the National Park Service (NPS) hired me to be an Entrance Station ranger at Crater Lake. I wore the ranger uniform with pride as I welcomed visitors to Crater Lake and charged them the $5 entrance fee. I was working in a tiny entrance station booth, which was more like a box. The park entrance road was surrounded by the tall skinny lodgepole pine trees. Except for the stream of vehicle traffic in the summer, it felt like I was working in the woods.

For the summer of 1997, it was soul satisfying to return to this Crater Lake entrance station ranger job. That summer NPS changed the job title to Visitor Use Assistant. I did not care what they called me. I was delighted to spend my summers at Crater Lake. I typically worked at Crater Lake from early May into sometime in October. I skipped the summers of 1998-2001 to work year-round as a natural guide in the Everglades. I returned to work summers at the Crater Lake entrance stations from 2002 to 2005.

My first seasonal winter jobs working in Everglades National Park, Florida 1992-1995

The weak point of the Crater Lake jobs was that they were only temporary summer jobs. Thus, I had to find another seasonal job for the winter in those months to mark time before returning to Crater Lake for the summer. Fortunately, the peak season for Everglades National Park visitation in Florida was from late November to early April. I arrived at the Flamingo Outpost in Everglades National Park in December 1992. My first job was working in housekeeping. I then transferred to a Front Desk job at the Flamingo Lodge.

Unlike Crater Lake, I was disappointed with my first views of the Everglades. The sawgrass prairie, which made up much of the park, looked as flat as the eye could see. It looked like a Midwest farm field, not at all like the iconic western national parks with towering mountains. The only high features in the Everglades were the lofty clouds that I had to imagine they were as high and dominating as the Rocky Mountains, Cascades or Sierra Nevada Mountain ranges.

My seasonal housing unit looked out into the subtropical Florida Bay, which made up the lower third of Everglades National Park. Numerous mangrove islands dotted the shallow Florida Bay. In the western part of the bay, the water blended into the Gulf of Mexico. As a child growing up in the landlocked St. Louis, Missouri, I dreamed of living close to the ocean to see that horizon line where the ocean met the sky with no land to interfere. Flamingo was probably the cheapest place in Florida to live next to the ocean, even if Florida Bay was considered an estuary, a place where inland freshwater met and mixed with seawater from the ocean.

It felt very tranquil to live by so much water. Surrounding our housing area and Flamingo were subtropical mangrove trees living in the shallow waters and coconut palms stood by the higher solid grounds of the buildings. The Everglades had a fascinating variety of wildlife with alligators, crocodiles, dolphins, manatees, deer, raccoons, and a wide variety of colorful wading birds. November to April is the dry season in the Everglades where it rains occasionally and is most sunny most of the time. The high temperature from December to April is in the upper 70s to lower 80s. South Florida is a fun place to comfortably wear shorts in the depths of winter.

To mark time until I could return to Crater Lake, I made the best out of working winters in the Everglades. I skipped two winters in 1993-94 and 1994-95 to spend time with family in St. Louis. I returned to Flamingo in the winter of 1995-96 to work as a night auditor at the lodge front desk. I thought I would use my Business Administration college degree to do this accounting job to balance the daily receipts at the lodge. Like my 1995 summer at Crater Lake, I was a glutton for punishment working this overnight job. It was stressful to complete all the office work in time. The computers were finicky and glitchy with no one around to assist if I ran into technical issues. It was a brutal sleep schedule and hard on my dating relationship at that time. I vowed to never do that job again.

Working as an Everglades naturalist boat tour guide 1998-2002

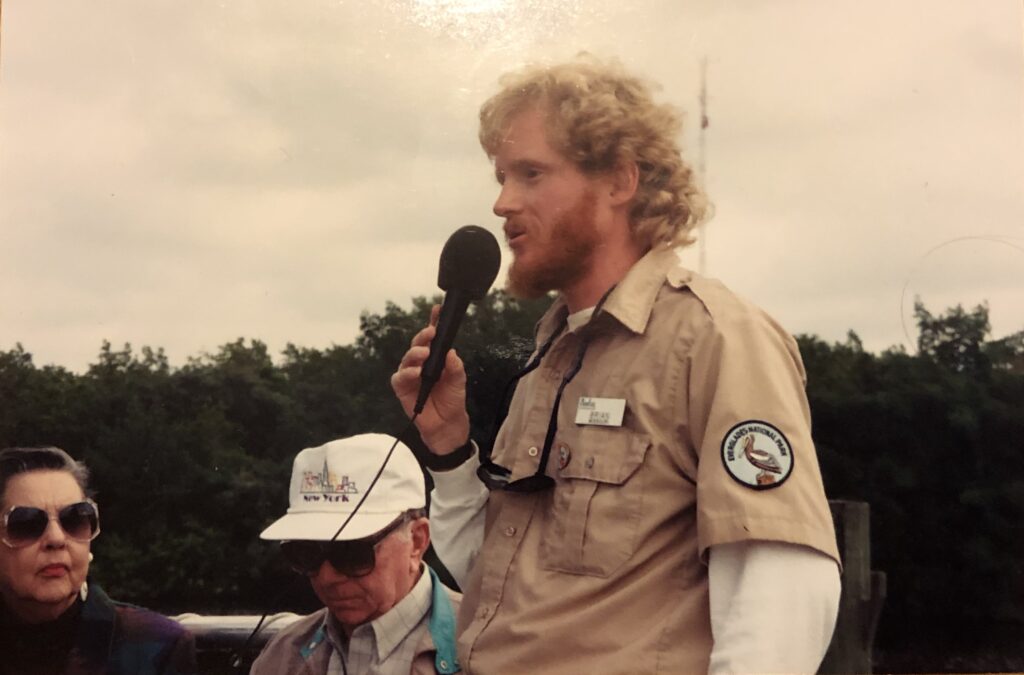

I skipped working in the Everglades in 1996 to 1997 to visit family in St. Louis. It was good to be home that winter because to be at the hospital hours after my oldest niece and goddaughter, Rachel was born. When I returned to Everglades National Park in November 1997, I worked front desk at the Flamingo Lodge. In early January 1998, a naturalist guide position opened to narrate the boat tours in Flamingo. I applied for the position and started in late January 1998.

In the summers of 1992-1994 at Crater Lake, I volunteered to lead church services at the campground amphitheater on Sunday mornings for A Christian Ministries in the National Parks (ACMNP). I grew up as a church going Christian, plus I was influenced by my maternal grandfather, Arthur Johnson Sr, who was a charismatic Baptist Minister. Since I was a child, I enjoyed giving speeches at school. ACMNP recruited me while I was in college to volunteer for them leading church services in a national park and they would find a job for me. They found my first gift store job at Crater Lake in the summer of 1992 and my housekeeping job working in Flamingo in the winter of 1992. Thus, I was an ACMNP volunteer in Everglades National Park during the winter of 1992-93.

I liked the opportunity to do public speaking leading the church services. It was extra responsiblies while working full time in the national parks. The good news was that it was typically a new group of visitors attending each weekend. I could recycle my sermons and not necessarily come up with a new talk every weekend. As I worked in the national parks, I knew that I eventually wanted to become an interpretive park ranger. They lead the public ranger talks, guided hikes, guided canoe trips, narrating boat tours, presenting evening campfire programs, etc. They looked like they had the most fun of any job working in the national parks. Flamingo had the tradition of the ACMNP volunteer leading the sunrise Christmas and Easter boat trip each year.

Everglades did not have an ACMNP volunteer to lead the Christmas morning sunrise tour in December 1997. I volunteered to lead the service. The service went exceptionally well. We had over 40 people on board the boat that held over 97 people. It was an astonishing sunrise over Florida Bay. I spoke briefly on the meaning of Christmas before we experienced a captivating sunrise. Leading that service helped me land the concession naturalist job. The lead naturalist, Rob Parenti, was on board that board that morning as the first mate to assist the boat captain. He saw me in action. Rob noticed I was very comfortable with public speaking. He joked after I got the Flamingo boat tour naturalist guide job that he knew I would be a good fit because he could tell that “I liked to talk a lot.”

This naturalist boat tour guide job was my first time talking full time for a living. I loved that job at the time. I narrated two different boat tours, one into the more open waters of Florida Bay and the other boat tour up the Buttonwood Canal into the backcountry waters of the Everglades. I pointed out alligators, crocodiles, manatees, dolphins, and various wading birds to the boat passengers. It was fun to learn about the history of the Everglades, the Native Americans, and the outlaws that settled in the Everglades.

It was great to talk about how and why the Everglades became a national park in 1947. Unlike western national parks which were protected for their dramatic scenery, the Everglades National Park was the first national park in the world protected for its biodiversity. Florida conservationists wanted it protected because of its wide diversity of plants and animals.

I greatly admired “The mother of the Everglades” Marjory Stoneman Douglas who fought many years to protect the Everglades. She wrote the most renowned 1947 book, The Everglades: River of Grass. She opened the book by writing,

“There are no other Everglades in the world. They are, they have always been, one of the unique regions of the earth, remote, never wholly known…The miracle of the light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slow-moving below, the grass and water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades of Florida. It is a river of grass.”

I shared that quote and others from Marjory Stoneman Douglas during my boat tour narrations. She lived to 108 years old. She passed away in May 1998, just months after I became an Everglades naturalist guide. It felt like her torch moved on to me and others in my generation to cherish and protect the Everglades. When possible, I made sure park visitors knew about her during my interactions.

Most of all, this job gave me a great opportunity to talk about the importance of saving the Everglades, our precious environment, and our planet from the harm caused by humans. In most of my programs, I talked about how the Everglades was one of the most threatened national parks in the United States due to over development and over drainage. In December 2000, Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed a multi-billion-dollar plan to try to save the Everglades.

I ended most of these narrations with a famous quote incorrectly attributed to Marjory Stoneman Douglas to this day. In fact, a lesser-known Everglades activist named Joe Podgor gave Marjory the iconic quote: “The Everglades is Test. — If We Pass, We May Get To Keep The Planet.”

At that time, I felt like I was doing what I could to save the planet by narrating those boat tours. I hoped I planted some seeds to inspire some individuals, especially younger individuals on these boat tours, to become environmentalists.

Working as an Everglades City winter seasonal interpretation ranger 2003-2007

By the spring of 2002, I was burned out narrating the Flamingo boat tours. I was tired of fighting with boat captains. I had enough their giant egos who were not interested in providing quality customer service and working as a team with me to provide a lifetime experience with the passengers. I detested the 10-hour days in the winter leading up to 4 two-hour tours. It was too much talking for me and started to strain my vocal cords. I became so concerned that I went to see a doctor about that. I had lost faith in the Flamingo management that did not care for my well being and low pay with the long hours and impacts on my health.

On top of all that, I missed Crater Lake National Park and the western part of the United States. I was tired how flat south Florida was. I wanted to see hills and snowcapped mountains again. Fortunately, my friend Amelia Bruno, who oversaw the Entrance Station fee program at Crater Lake, offered me my old seasonal job back of working at the entrance station. Just a few months before, I bought my first car a green (my favorite color) 2002 manual transmission Honda Civic, which I still own to this day. I wanted to go for a long cross drive in my new car.

I never worked at Flamingo again. I had a wonderful summer at Crater Lake. It was a superb summer for me to return because the park was celebrating its centennial. Congress passed a bill establishing the national park and President Theodore Roosevelt signed it into law on May 22, 1902. It was great to make new friends working in the park since I was gone for four years. It was a joy to rediscover all the trails in the park that I enjoyed hiking.

The stressful part was I did not know what I was going to do for the winter of 2002-03. I ended up going back to St. Louis to stay with my parents. I returned to the entrance station ranger job the next summer. In the summer of 2003, I had a new housemate at Crater Lake, David Grimes. He had worked seasonally in other national parks such as Congaree Swamp in South Carolina and Zion National Park. We struck up a friendship. We both applied to work as seasonal interpretation rangers in Everglades National Park that winter.

As summer turned to fall, Grimes (as he likes his friends to call him) accepted a winter seasonal position in the Everglades City district in Everglades National Park. Unfortunately, I received no word for a winter position in the Everglades. I decided to return to St. Louis for the winter, not sure what I planned to do after I returned there.

In late November, I received a phone call from Candice Tinkler, the District Supervisor Ranger at the Everglades City Visitor Center. Someone she hired for the winter declined to work there. She needed to hire a new ranger fast. She saw my name on a list of eligible candidates. Grimes highly recommended me, so she called to offer me an interpretative ranger position for the winter. She needed me to come down fast, within a week if possible. I started throwing my ranger uniforms and other belongs in the car to drive from St. Louis to Everglades City, Florida. I left shortly after Thanksgiving and arrived during the first week in December.

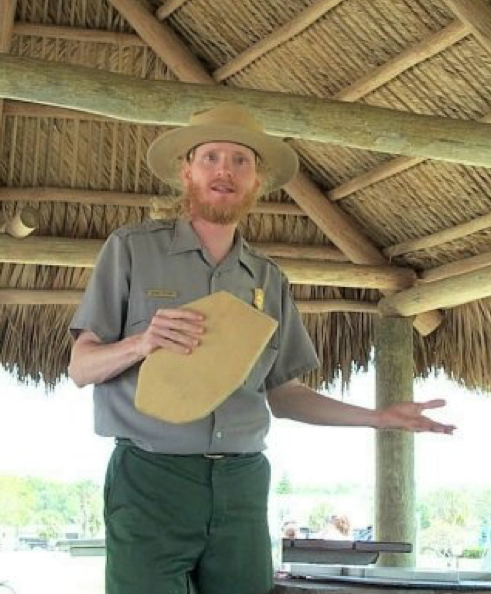

This was my first National Park Service interpretative ranger job. After my four years as a naturalist guide in Flamingo, this new ranger position was a ideal fit for me. I enjoyed narrating the boat tours in Everglades City, narrating the canoe trips, and giving ranger talks on the water drainage issues and the Everglades Restoration plan. I liked spending the winter in Everglades City and I ended up spending three more winters there from 2004 to 2007.

In subsequent winters working in Everglades City, I expanded to do additional ranger programs, such as guided bike tours and an evening program on the birds of the Everglades. At that time, I knew nothing about PowerPoint. Candace Tinkler left Everglades City in 2005 to work in Redwoods National Park. The new District Supervisor, Sue Reese, quickly taught me how to put together a PowerPoint presentation. I became quickly hooked on PowerPoint to create presentations. I am still enamored with PowerPoint to this day, as well as Mac Keynote since 2013, to create over 100 climate change talks since 2010.

Sue gave me an opportunity to be creative to make a temporary display in the visitor center honoring Marjory Stoneman Douglas with pictures, quotes, and brief information about her. She allowed me to create a wooden box with a mirror on the inside. The visitor center had a small display about the ecological damage and restoration plans for the Everglades. The wooden box hung by those displays. On the outside of the box, I printed out a sign, “Look inside at the person most responsible to save the Everglades.”

When the visitor opened the box, they would see a reflection of themselves. The other rangers and park visitors got a good laugh out of my display. I doubt that box with that message is still there today. However, I loved the message I conveyed that each of us is responsible for saving the Everglades, the environment, and the planet. No excuses.

My first seasons as an Interpretative Ranger at Crater Lake National Park 2006-07

I delighted as a winter seasonal interpretative ranger in Everglades City from 2003 to 2007. During those winters, I became eager to become a summer interpretative ranger at Crater Lake National Park. I applied to be a summer interpretative ranger at Crater Lake in 2005. However, Martha Hess, the Interpretative Supervisor Ranger at Crater Lake, decided that I was better suited to stay as an Entrance Station Ranger. I felt dismayed when she shared that with me. However, I was not discouraged. I applied the next winter and Martha called me in May 2006 offer me a summer season interpretative ranger position at Crater Lake. I dreamed for several years hoping to get this position. I felt ecstatic when she extended the job offer to me.

Like my previous winters working interpretation in Everglades National Park, I was overjoyed working as an interpretative ranger at Crater Lake National Park in the summers of 2006 and 2007. After many years of working other jobs at Crater Lake, I felt triumphant leading a lodge talk about the park founder William Gladstone Steel, giving a geology talk, and narrating the boat tours that summer. In late August, I had to debut a junior ranger program and an evening campfire program when other rangers left for the season to return to their teaching jobs.

I loved using PowerPoint, but I found it stressful to pull together an evening program while working full time without much office time to craft it. I pulled a couple of all-nighters without much sleep, and I presented a new evening on the birds of Crater Lake at the campground amphitheater in late August 2006. It was a huge relieve to have this ranger program completed. Most Crater Lake rangers are required to debut their evening program in their second season at Crater Lake. However, Crater Lake was short of rangers to give evening programs in August 2006. Thus, I was required to present an evening campfire program my first summer.

I received good audience responses from my Birds of Crater Lake evening program. It soon became my favorite ranger talk. I loved making the campfire and interacting with the large audience of visitors before, during and after my evening ranger program. When I returned to Crater Lake for 2007, I was eager to give this talk. After I had created this program, I was thankful Grimes pushed me hard to debut it in 2006. Otherwise, like most Crater Lake interpretive rangers, I would have spent the winter worried about constructing this program.

The lead interpretative ranger, David Grimes, was impressed with my Lodge talk I put together about the founder of Crater Lake National Park, William Gladstone Steel. He thought we should videotape my talk. We would then submit the video to the NPS Interpretative Office as Harper’s Ferry to see if they would certify this program. We filmed my talk in August 2006. I waited that winter to see if the NPS Office certified this talk.

When I returned to Crater Lake in June 2007, I received the good news announced during seasonal training that they certified my talk. Twelve years later, I uploaded this video to YouTube so you can see this talk. Learning about William Gladstone Steel when I assembled this talk had a big influence on my life. I wrote about him earlier this year, The historical person who inspired me to be a Climate Lobbyist.

In 2007, I had a terrific summer as an interpretative ranger at Crater Lake. I worked hard the previous summer to create all my ranger programs. Thus, I could enjoy my free time more in early July knowing that my ranger talks were ready from the previous summer. I just had to review my notes for all these programs. I felt like I improved each time I gave these ranger programs. It was a terrific summer, but then tragedy struck.

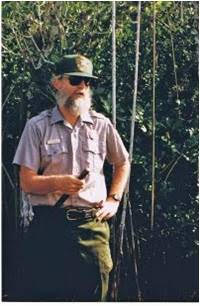

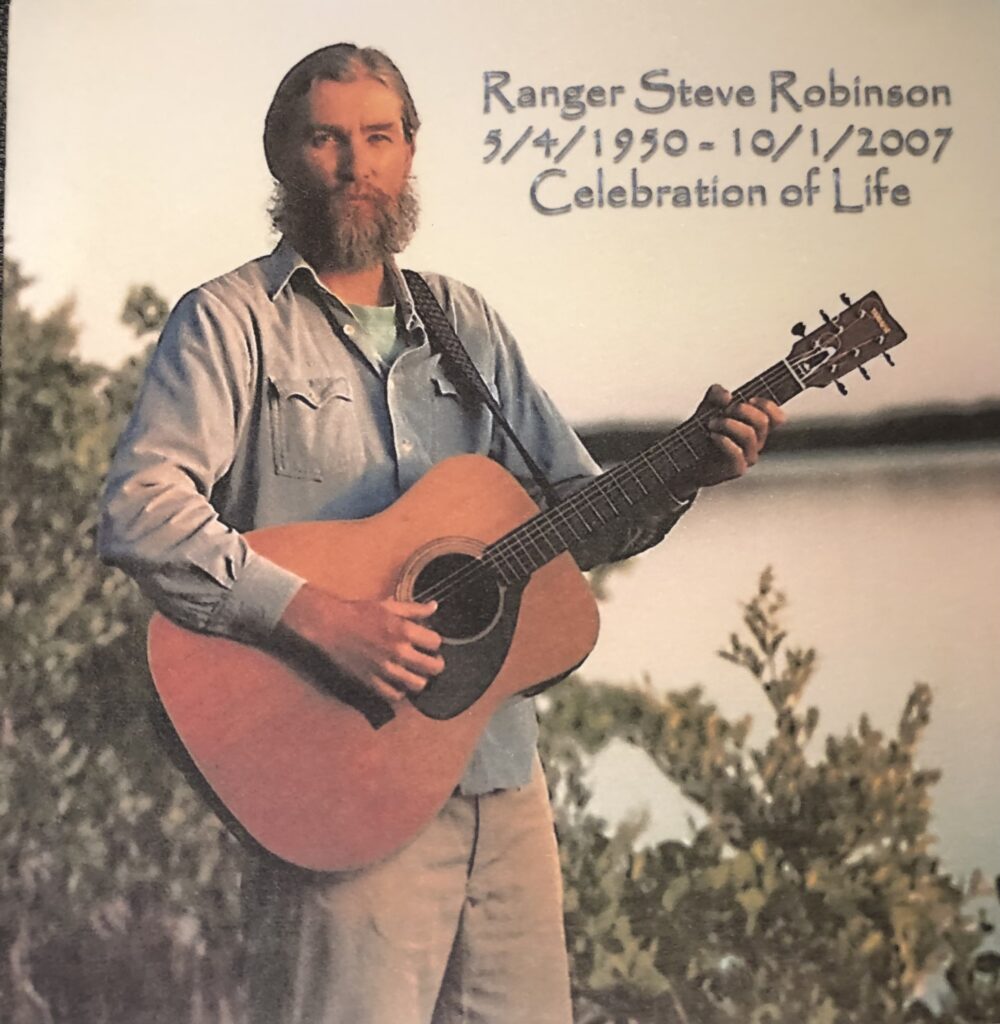

The tragedy of losing my Everglades and Crater Lake mentor, Steve Robinson

In August 2007, we received news that fellow Crater Lake ranger Steve Robinson had pancreatic cancer. It was stage 4 and incurable. I knew Steve since I attended his ranger evening program in Flamingo in Everglades National Park in February 1993. When I returned to Crater Lake National Park for the summer, he narrated the boat tour I traveled on as a passenger in July 1993. I discovered that Steve and his wife Amelia Bruno were seasonal park rangers like me that spent their winters in Flamingo and their summers at Crater Lake.

In the years that followed, I stuck up a friendship with Steve and Amelia. He became a mentor to me how to be a good ranger, human being, and a man. When I worked in Flamingo and Crater Lake, I came to Steve and Amelia’s house to spend hours with Steve to learn his wisdom.

I learned a lot from Steve trying to absorb his wisdom. At that time, I wrote down inspiration quotes from to pin on my bedroom bulletin board. Steve was an optimist who would respond to cynicism, “Just because it has not happened yet does not mean it can never happen.”

Steve was a fourth generation Floridian who had a deep love for the Everglades and natural world. For 25 years, he worked as a seasonal park ranger in Everglades National Park. Steve had the good fortunate to meet the ‘Mother of the Everglades’ Marjory Stoneman Douglas one time when he worked as a ranger. He happened to see her at one of the scenic overlooks in the park and struck up a brief conversation with her when they were both admiring a scenery. Steve loved to quote Marjory and share her stories.

Steve had the gift of connecting with park visitors and people caught up in momentary short term, knee jerk, superficial thinking. One time, Steve told me, “My goal in life is to remove the rocks that other people’s paths.”

Steve had great stories to try to shift other people’s perspective. At the start of my March 8, 2012 blog and March 2012 Toastmasters speech, I shared this story about Steve. In his spare time as a seasonal ranger in the Everglades, Steve would drive up to a scenic overlook in the park known as Pa-hay-okee. He loved to sit there and look over the beautiful scene of a saw grass prairie stretching out to the horizon as far as the eye could see. One occasion, when he was there for a time, a park visitor drove his car up to the nearby parking lot. The visitor grabbed his camera from the car and quickly ran to the overlook. When he got there, the visitor felt disappointed in the lack of action and the flatness of the plain saw grass vista. He mumbled, “Nothing.”

Steve smiled at him. He looked at the sawgrass prairie, stretched out his arms, and proclaimed “Everything.”

The last several summers that Steve worked at Crater Lake National Park, he worked at the Watchman Peak Fire Lookout. He would scan for wildfires. In addition, he relished the opportunities to engage with park visitors who hiked the trail, which was less than a mile long with over an elevation gain of 420 feet. The view at the summit provided one of the best panoramic views of Crater Lake and the surrounding area. Visitors often were flabbergasted on the summit, unsure of what to say with this 360 bird’s eye of view of the area. One visitor commented to Steve, “Looks like I reached the end.”

Steve was amused by the statement. He responded, “No, you reached the beginning.”

Steve and I laughed at this story because I could totally relate. As a park ranger and avid hiker, I observed that visitors often did not know what to do when they reached a mountain summit. Some look disappointed or restless because they hoped for something more. Others would quickly enjoy the view, but then they hurry down eager to get to their next destination or point of interest at Crater Lake. They use a mountain summit to like a mental check list of something that they conquered and then they wanted to move onto their next goal.

Steve and I both looked at a mountain summit as a place for deep reflection. A place to truly enjoy the view. It’s a spot to truly ponder life and our place in the world. A location to bring a lunch, meditate, read a book, and observe the world. With patience, one might see a bird soaring or other wildlife. It’s a great place to people watch or even start up a conversation with a stranger, as Steve liked to do there. Steve and I both thought of a mountain summit as the beginning, not an end. It’s a place for renewal and to reflect upon our lives.

One of the pearls of wisdom that Steve gave to me was, “Every single person makes the world every single day.”

A mountain summit can be an ideal spot to contemplate that.

In August 2007, I assumed I had years to absorb Steve’s knowledge. It shocked me when I learned he had stage 4 pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest and aggressive forms of cancer. I visited Steve often in the hospital as his health deteriorated. During my hospital visits, he was too weak and on too many medications to talk. Sadly, Steve passed away on October 1, 2007.

I was in a daze for a year after Steve’s death. His mortality made me re-exam my own life. Steve’s quick passing at the age of 57 years old showed me that tomorrow and a long life is not guaranteed. Steve truly made the most of his life as a park ranger, musician, husband, father, friend to many, someone who loved all people, and a mentor to me. He loved life and lived everyday like it was a gift to be alive. After Steve’s death, I felt lost no longer having my mentor around. I needed to do something different with my life to overcome the loss, make the most of my life. I wanted somehow be beneficial to the world as Steve was when he was alive.

Transitioning away from spending my winters in Everglades National Park 2007-08

In early September, around the same time that my mentor Steve was tragically losing his battle to pancreatic cancer, I received an email from my Everglades City District Supervisor Sue Reece. She told me that she would be happy for me to return to Everglades City for the winter. However, she had an opening for a winter seasonal ranger in the Shark Valley area in Everglades National Park. She thought I could be a good fit to work there. The Supervisor Ranger at Shark Valley at that time, Maria Thomson told Sue, ‘I want a good seasonal interpretative ranger to work at Shark Valley this winter. Someone who cares about the Everglades and can relay that to visitors. Someone like Brian Ettling.’

With Steve’s prospects of recovering from pancreatic cancer looking dim in September 2007, I needed some good news. It was heartwarming to hear that I was needed in Shark Valley. Therefore, I decided to work at that location in Everglades National Park for the winter. I would be narrating the tram tours, giving a short ranger talk, leading bicycle tours, and possibly providing a guided bird walk. This looked like a good opportunity to try a new location in the Everglades. Maria hoped I would work there. I had an opportunity to make a difference there.

When I arrived in Shark Valley in November 2007, it did not feel like a good fit for me. I had a housemate with a very surly personality. I missed my friends in Everglades City and other parts of the park. I felt like I was living in the middle of nowhere off of Hwy 41, the Tamaimi Trail. The park housing was just a few miles west of Shark Valley, but it felt very isolating there. I could not sleep at night, and I fell into a very bad depression. I wanted to leave the Everglades, but I did not know where I wanted to go.

In my sleeplessness, depression, and restlessness, I found my life’s purpose. I wanted to carry forth my mentor Steve’s message of protecting our Earth and environment since he could no longer share that vision with others.

I recalled 1998 when I started giving ranger talks in Everglades National Park. Visitors then asked me about this global warming thing. Visitors hate when park rangers tell you, “I don’t know.” Visitors expect park rangers to know everything. Don’t you?

Soon afterwards, I rushed to the nearest Miami bookstore and to the park library to read all I the scientific books I could find on climate change.

The information I learned really scared me, specifically sea level rise along our mangrove coastline in Everglades National Park. Sea level rose 8 inches in the 20th century, four times more than it had risen in previous centuries for the past three thousand years. Because of climate change, sea level is now expected to rise at least three feet in Everglades National Park by the end of the 21st century. The sea would swallow up most of the park and nearby Miami since the highest point of the park road is three feet above sea level.

It shocked me that crocodiles, alligators, and Flamingos I enjoyed seeing in the Everglades could all lose this ideal coastal habitat because of sea level rinse enhanced by climate change.

By the winter of 2007-08, I had read a number of books on climate change. I saw the documentary film about Al Gore, An Inconvenient Truth, and read the companion book in 2006. I knew I needed to do something on climate change, but I did not know what. I was very clear though that I was not going to find the answer by continuing to work winters in the Everglades. It was time for me to move on with my life. In the winter of 2007-08, I was burned out of the south Florida climate, flatness, and the long cross country drive to spend the winter in the Everglades. Even worse, as a single man, it seemed like I was not going to find a wife there.

I said goodbye to the Everglades at the end of April 2008. I decided I would spend my winters in my hometown of St. Louis Missouri to organize for climate action. I had no idea how I was going to do that, but I was excited I found my life’s purpose.

Creating a Guided Ranger Hike in Summer of 2008 using my wisdom and Steve Robinson’s

In late May of 2008, I returned to work at Crater Lake National Park for the summer. Soon after I arrived in the park, I mentioned to my superiors that I wanted to give a ranger program about climate change. My Crater Lake supervisor, Eric Anderson, and the lead interpretive ranger, David Grimes, supported and encouraged my idea. I just did not feel like I knew enough or was brave enough to do such a program. It would take me three more years before I felt courageous and had enough knowledge to give my climate change evening program at Crater Lake.

For the summer of 2008, David Grimes announced in early June that we had a large enough staff for the first time in years to lead ranger guided hikes up the Watchman Peak. Standing barely over 8,000 feet tall, the Watchman Peak is located on the western side of the Crater Lake rim. It receives the deepest snow accumulation in the park with snow drifts up to 50 feet thick. In some years, the West Rim Drive does open for the season until late June. This is due to the time it takes for the road snow removal crew to plow the tremendous amount of snow on the West Rim Drive, especially around the Watchman Peak.

After West Rim Drive opens sometime in June, it takes another month for the snow to melt back for the trail to the Watchman Peak summit to open. Thus, the ranger guided hikes would not start until the end of July. The summer of 2008 would be my first opportunity to lead a ranger guided Watchman Peak hike. I had several months to prepare. Ranger David Grimes allowed me to shadow one of his first hikes for the season at the end of July. I would then have about a week to prepare for my own Watchman Hike in early August 2008.

After I saw Ranger Grimes’ hike, I had ideas how I would create my own guided ranger hike up the Watchman’s Peak. I wanted to give the visitors on my hike a “mountain top experience” using the wisdom I had accumulated as a person, a park ranger, and the advice I received from my mentor Steve Robinson. When visitors went on guided hikes, I used to ask them as a park ranger, ‘Why are you going on this ranger hike?’

Visitors often replied, ‘Because I want to learn something. I don’t feel like I know anything about this national park or trail. I feel like the ranger can share something that I did not know.’

Thus, I determined to construct my hike around the visitor longing to learn something insightful from the ranger. I thought I would even give them something to take home with them for their next hike when I was not with them.

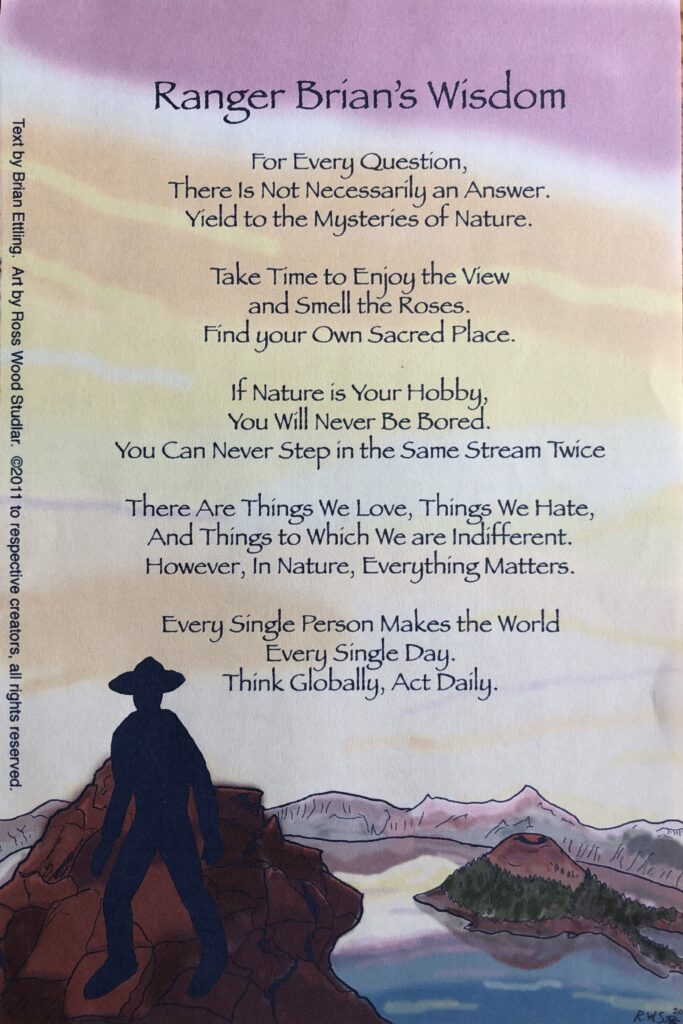

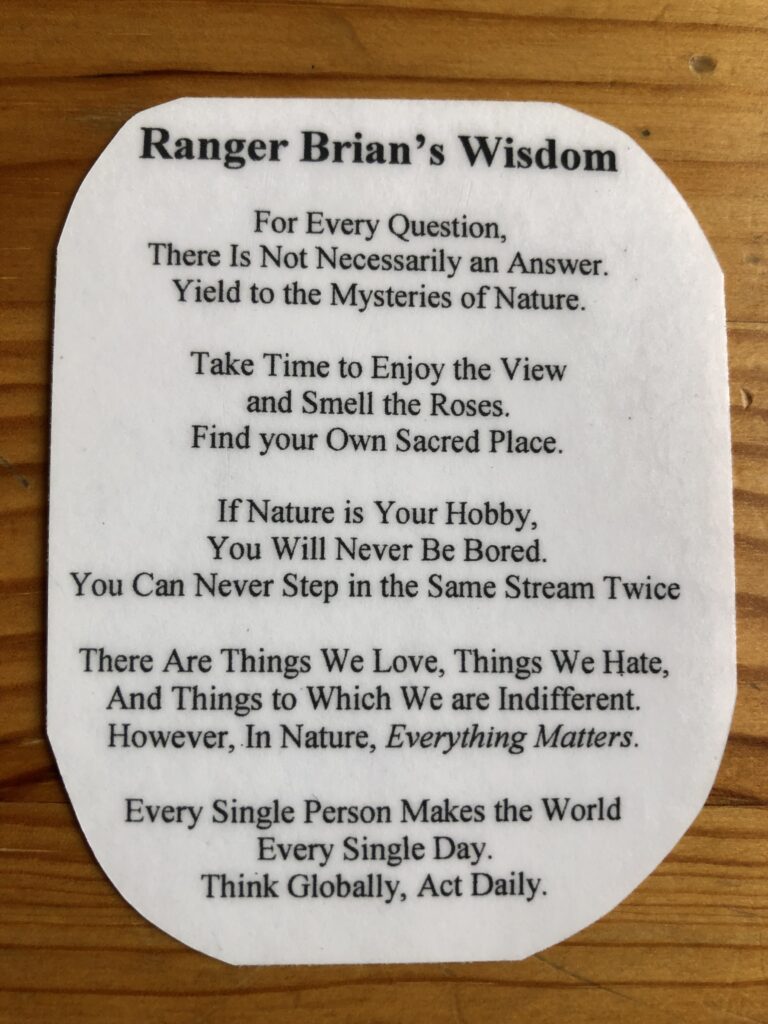

I decided to give each person attending my hike a pocket-sized card to take home with them called “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom.” I would present it to them at the conclusion of my hike. It would be at my last narrated stop, which was a short distance before the Watchman summit and the fire lookout. A tip that you quickly learn as a national park ranger or naturalist guide: don’t talk during a sunset or sunrise. The audience will be absorbed in the moment taking pictures and watching the sun move on the horizon line. They won’t hear a word that you are saying.

I timed my talk so that I would give my gift 10 minutes before the sunset. If I tried to give my conclusion and my pocket-sized card less than 10 minutes from the sunset, the park visitors on my hike would skip my final stop to go to the fire lookout to watch the sunset.

At the introduction of my guided hike, I told my audience that the trail is always open. They are more than welcome to walk past me to hike to the summit. I don’t want to hold them back if they are anxious to see the view from the fire lookout and worried that they might miss the sunset. I assured them that I will be watching the time closely so that we will be at the summit in plenty of time to see the sunset. However, I warned them that if they blew past me to get to the summit, they would not receive my free gift right below the fire lookout.

Like kids waiting for gifts on Christmas morning, the visitors were anxious to know what gift I would have for them. They would even ask me during the introduction: “What’s the gift?”

I would coyly answer: “You will have to stay with me to find out.”

Giving out these pocket-sized gifts became very rewarding for me. I used these cards in May 2011 a Toastmasters speech I gave when I was a member of South County Toastmasters. This speech was a success with this Toastmasters group. I joined this club in February 2011. It was my third speech to the club. The members voted for me as “Best Speaker” for the first time in the three speeches I gave to the group. A fellow Toastmaster filmed most of this speech which I uploaded to YouTube five years ago.

The Significance of the words of “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom”

Steve Robinson passed away just one year previously on October 1, 2007. I started giving my Watchman sunset ranger guided hike in mid-August 2008. It was less than a year since I lost my mentor and friend. He was very much on my mind as I wrote out these words.

I remember Steve remarking,

“For Every Question,

There Is Not Necessarily an Answer.

Yield to the Mysteries of Nature.”

As a park ranger, visitors wanted me to have answers to all their questions. Sometimes there were no answers to some of their questions. The visitors would occasionally give me a frustrated look if I could not answer a question about Crater Lake, the Everglades, the wildlife, the age of specific tree, etc. I never wanted to lie or mislead visitors when I did not know the answer. In fact, there is beauty in the unknown. One can find joy in researching and finding a scientific answer to question. Or better yet, conducting research to answer a scientific question that has not been answered yet.

As far as my second three lines,

“Take Time to Enjoy the View

and Smell the Roses.

Find your Own Sacred Place.”

That might have been a synergy of thought between Steve Robinson and me. I was frequently dumbfounded as a park ranger seeing how rushed people were on a vacation to visit Crater Lake and the Everglades. I often wondered, ‘Are they really enjoying themselves?’

Even more, it astonished me how park visitors would tell me they were on a mission to see all the national parks. To those visitors, I would sometimes respond, ‘Don’t miss the good stuff in between the national parks.’ Or ‘After you see all the national parks, what are you going to do?’

I loved working and living as a summer seasonal park ranger at Crater Lake for 25 years and a winter seasonal ranger in Everglades National Park for 16 years. In between seasons, I cherished visiting Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Arches, Sequoia, Mt. Rainier, North Cascades, Olympic, Death Valley, and other national parks multiple times. I never had the mindset of ‘one and done’ with visiting a national park. I wanted to see the parks that I visited again and again.

Steve and I had many conversations about visitors who seemed to have mental checklists to visit as many national parks as possible and the sights within a national park once. With “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom,” I wanted to slip in a message to “Find your own sacred place.” Even more, it’s good to visit your happy place multiple times.

This was one of Steve Robinson’s favorite observations:

“If Nature is Your Hobby,

You Will Never Be Bored.

You Can Never Step in the Same Stream Twice.”

If one hung around Steve long enough, he would share this deeply held belief he had. He then would give stories of wildlife, weather patterns, and situations he encountered in nature. He was a master storyteller of his interactions in the outdoors.

When given a chance, Steve loved to preach this thought when he had an audience:

“There Are Things We Love, Things We Hate,

And Things to Which We are Indifferent.

However, In Nature, Everything Matters.”

When park visitors and friends would chat with Steve, they would assert that they hated snakes, mosquitoes, insects, wildfires, cold weather, etc. Steve would then get a twinkle in his eye and a charming smile behind his long beard. He would then find a way to politely counter that we might not like those parts of nature. It’s not necessarily his favorite things in the outdoors. However, Steve would point out that the things that we don’t like in nature that are not cute, fuzzy, adorable, and majestic are still a vital part of nature.

This was Steve’s quote, “Every Single Person Makes the World Every Single Day.”

It was an inspiring statement that had a deep impact on me when it heard Steve say it. I matter. You matter. Everyone matters. Every action we take every single day makes a difference in the world. That goodness I received from Steve’s gem of wisdom stays with me to this day..

Finally, I originated the line, “Think Globally, Act Daily.”

Decades ago, I saw that bumper sticker on cars “Think Globally, Act Locally.” My reaction was, ‘That’s nice, but some days I don’t want to act locally. However, I can act daily for the environment, our planet, and for our local neighborhood.’

I loved creating Ranger Brian’s Wisdom. I must have given way several hundred of these cards over the years. I laminated them so they would last longer. I always trimmed off the sharp edges with scissors at the Crater Lake interpretative work room, so visitors would not get paper cuts from handling these cards. Hopefully, these cards have planted some seeds to influence people to care for our parks, the environment, and our planet.

Videotaping my ranger guided Watchman Peak sunset hike

The visitors and David Grimes responded positively to my ranger guided Watchman Peak sunset hike. Grimes scheduled another seasonal ranger, Terra Kemper, to video this hike in September 2008. Like what occurred with my lodge talk in 2006, we submitted the video to the NPS Interpretative Office as Harper’s Ferry to see if they would certify this program.

When I returned to Crater Lake in June 2009, I received the good news announced during seasonal training that the NPS did certify my talk. Nine years later, I uploaded this video to YouTube so you can watch this talk.

I initially inserted the YouTube written transcript into this blog of my ranger guided Watchman Peak sunset hike, but it doubled the length of this blog. Thus, I decided against it. Hopefully, you will take the time to see the video or read the transcript on YouTube.

Final Thoughts

American author and environmentalist John Muir wrote,

“In every walk with Nature one receives far more than he seeks.”

My favorite memories as a child were exploring the woods by my parents’ house and hiking in nature by myself during family camping trips. I intuitively lived by the John Muir quote about the fulfillment I received from spending time in nature without an awareness of John Muir or this quote. I did not know about John Muir until I started working in the national parks.

In fact, you can sum up my life in this nutshell: I loved spending time in nature as a child. My first job out of college was working in the national parks so I could be close to nature. As I spent time in the national parks, I wanted to be a park ranger so I could educate others about the national parks and our natural world. As a national park ranger, visitors expected me to be knowledgeable about climate change. As I became informed about climate change, I decided to transition from a park ranger to a climate change organizer. As climate change organizer, I am now deeply concerned about the state of American democracy.

As I wrote this blog, I stumbled across another John Muir quote, “Between every two pine trees there is a door leading to a new way of life.”

That’s what happened to me. I had no idea when I took a seasonal gift store clerk job at Crater Lake National Park in 1992 how much it would change my life. When I hiked between the pine trees there, it completely led to a new way of life for me. I hope that others that visit and work in national parks experience a life transformation.

Even more, I had a mentor seasonal Ranger Steve Robinson who looked like a cross between John Muir and Dr. Suess’ The Lorax who was willing to guide me. He showed me how to be a better man, park ranger and ultimately a climate advocate. He taught and showed me that all my actions and interactions with others matter. As Steve liked to say,

“Every single person makes the world every single day.”

I am deeply proud of my 25 years as a seasonal park ranger at Crater Lake and Everglades National Parks. Every day was a blessing to work there. On my worst days living in the national parks, I dealt with situations such as feeling lonely, depressed, heartbroken after a relationship breakup, a bad encounters with park visitors, a demanding supervisor unhappy with my work performance, a difficult co-worker making an unhealthy work environment, and upper park or concession management creating toxic politics on the job. With all that, I might get very little sleep that night or subsequent nights. However, all I had to do was to walk outside. The serenity of the national parks renewed me with its peaceful energy embracing me and whispering, “You are going to be ok.”

It’s that energy of the natural world rejuvenating me as a park ranger that inspired me to become a climate change organizer to protect our planet.

Working in the national parks, over 97% of the visitors I met were good people who were happy to be there. They loved their families and partners deeply. They wanted to show their families, children, loved ones, and good friends some of the most beautiful scenic locations on the planet. They cared profoundly about nature, the environment, the outdoors, the national parks, and our world. It was park visitors who insisted I learn and care about climate change. For years, I was scared to talk about climate change, fearing I would receive arguments from park visitors. When I started giving climate change talks at Crater Lake in 2011, it was park visitors who were very supportive, enthusiastic, and encouraging me to keep speaking out on that topic.

John Muir noted, “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.”

Last month, on a weekend in September 2023, my wife, her parents, 8 of her Danish relatives, my in-law’s best friends, and I (14 of us total) visited Glacier National Park. It was one of the most magnificent places I saw in my life. I stopped working at Crater Lake National Park in 2017, six years ago. Yet, I felt like I was home when I went to Glacier. I could immediately relate to the John Muir quote that “going to the mountains is going home.”

Sadly, Glacier National Park had little visible signs of glaciers from areas that we traveled by car, boat, and foot. Like my experience working in the Everglades and Crater Lake, Glacier sent a very loud message to ‘Please take action to reduce the climate change threat.’

I understood this clear and loud message. I ensured others got the message with my two previous blogs about seeing climate change at Glacier National Park calls for climate action. Visiting national parks for a day or working in them for 25 years should change us as individuals.

Edward Abbey penned so splendidly, “A man or woman could hardly ask for a better way to make a living than as a seasonal ranger for the National Park Service.”

It truly was a gift to work and live in the national parks for 25 years as a ranger. I hope my experience and wisdom I gained from that experience can benefit others, such as you.

P.S. Should I have given more credit to Steve Robinson in “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom?

As I write this blog in October 2023, I am wrestling with the realization that half of the thoughts on my pocket sized card for “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom” came from Steve Robinson. My original thought was to call it, “Advice from a Ranger.” This title would have been more broad to allow for that the advice was a combination of Steve Robinson’s and mine. I used that title, “Advice from a Ranger” for my first couple of guided hikes on Watchman Peak in 2008.

I showed my “Advice From A Ranger” card to Steve’s widow, Amelia Bruno. She was touched I had written this to honor Steve as well as my own advice for park visitors. She immediately posted it on the bulletin board at her Crater Lake Fee Program Manager Office.

At that time, I was influenced by Ilan Shamir‘s Your True Nature collection that was sold at the Crater Lake Visitor Center gift stores and elsewhere. Ilan’s company is now called Advice for Life by Your True Nature. Ian’s story is that he was a former marketing businessman with 7UP and free-spirit backpacker. One day in 1999, Ilan walked by a tree in his Colorado neighborhood that he frequently noticed. This time he stopped at the tree and asked for advice. Ilan heard the tree say to him: “Stand tall and proud…Be content with your natural beauty… Go out on a limb!”

Ilan turned the tree’s wisdom into a poem, “Advice from a Tree,” He then included it in his book Poet Tree: The Wilderness I Am. In 2000, Ilan started the Your True Nature Company with the “Advice From a Tree” poster. Then came a bookmark, minibook, and postcard giving the tree’s advice. Then inspiration hit him to share the advice of the river, mountain, garden, and hummingbird. He went on to pen the advice of the bear, moose, owl, horse, dog, butterfly, etc. Ilan and his company now offers more than 50 different advice by animals, plants and natural places.

I shared my “Advice from a Ranger” card with Vickie Grieve, Executive Director at Crater Lake Natural History Association, which runs the Crater Lake Visitor Center gift store. Vickie was thrilled that Ilan’s “Advice from a Tree” and the other Your True Nature Advice items sold in the Visitor Center inspired me to write “Advice from a Ranger.” Vickie knew Ilan personally and she gave me his email address.

I emailed Ilan in early 2009 and I did hear back from him on March 9th. He wrote:

“Brian,

Thanks so much for the Advice from a Ranger poem. I will show it around here in the office and be back in touch soon.

Ilan”

The next day, I responded:

“Ilan,

Thanks for the nice e-mail. I am always hoping that when I do a ranger program that I am making a difference and people might remember it months later. I enjoyed composing the Adviced from a Ranger. Half of it was inspired and is attributed to my mentor, Steve Robinson. He was a naturalist ranger at Crater Lake and Everglades National Park for over 25 years. Unfortunately, he passed away from cancer less than a year and a half ago. He used to love to share his thoughts and observations with me. The other half is just thoughts and observations from my time of being a ranger.”

Ilan replied: “Thanks Brian… for sharing about the creation of Advice from a Ranger. What are your thoughts on how you would like to see it used?”

I wrote: “As far as my thoughts for advice for a ranger. I am open to any suggestions you might have. I thought about selling them alongside your Advice poems. I would only want my poem to compliment, not compete against your poems. Your advice poem series certainly inspired me to create my Advice from a ranger. I had never heard of them until I saw Vickie Grieve selling them in the Crater Lake bookstores. Vickie seemed interested in selling my advice poem in the bookstore too when I first showed it to her last fall. However, we both wanted to seek out your input before we proceeded.

I thought selling them as bookmarks, postcards, and possibly even notecards. I have never sold anything artistic before for retail. Thus, I would like your advice. I would be more than willing to split and profits and revenue with you. I am willing to shorten or edit the contents, if you felt that was needed. I am very flexible. I am visioning a green backdrop with mountains and a river, maybe even an arrowhead, similar to the NPS logo. I thought it would be fun to have a drawing of a ranger. Again, I will be curious to your thoughts and ideas too.

Again, I do not want to compete again your advice series. I think they are so beautiful and inspiring. Furthermore, they inspired me when I had to create the content for my ranger sunset hike at Crater Lake. The visitors attending my program have really seemed to enjoy receiving them too. If I could make my Advice from a Ranger Poem marketable and sell them, but in a way that honors your product too, that is my goal.”

Unfortunately, I soon received a cease and desist letter from Ilan’s attorney that I could no longer use the title, “Advice from a Ranger.” I felt crushed. The email was very cold and unfriendly. I went from hoping to partner with Ilan on this project to losing respect for him. Vickie Grieve and Amelia Bruno both advised me to change my card to a different title. Thus, we agreed upon “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom.”

Since half of the thoughts on the card were Steve Robinson’s, I now wonder if I should have called it, “Ranger Brian and Steve’s Wisdom.” However, that seems to be a long title. For Steve Robinson’s quotes on my pocket sized card, I now wonder if I should have directly cited him. However, at that time, Amelia was fine with me calling it, “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom” and how I displayed the information on the card. Thus, I kept the title and content simple to this day. If you watch my Watchman Peak Hike YouTube video where I discussed “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom,” you will notice I talk a lot about Steve Robinson.

With a new title, Vickie seemed interested in selling “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom,” at the Visitor Center Gift Stores. She advised me to create quality artwork with it so she could present it to the Crater Lake Natural History Association Board of Directors. Two years later, I asked fellow Crater Lake interpretative park ranger Ross Wood Studlar, who is a cartoonist and illustration artist, to create artwork for my “Ranger Brian’s Wisdom.” Ross created a lovely color drawing.

In 2011, I presented Ross’ color artwork and my text to Vickie to present to the Board of Directors. Sadly, they voted to decline to sell the product that Ross and I created. Their decision stung, but I quickly forgot about it as I became devoted in 2011 to follow my passion as a climate change advocate.