For over 30 years, I had a life goal to visit Glacier National Park in Montana. As a child growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, I dreamed of living somewhere far from my hometown. I considered the local scenery with the rolling Ozark Mountains and the wide dominating Mississippi River to be lovely, but also bland. I wanted to live close to dramatic high snowcapped mountains.

Fortunately, after I graduated from William Jewell College in Kansas City, Missouri in May 1992, I took a summer job working at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. This was my dream came true to live at a high elevation of over 7,100 feet surrounded by majestic mountains topped with glistening snow. It was a magnificent national park to work, hike, explore, and live in for the summer. Working at Crater Lake during the summers from 1992 to 2017, I craved to see other American national parks with spectacular scenery.

When I worked at the Crater Lake National Park gift store from 1992-1994, I would thumb through their picture books of other national parks longing to see those places someday.

Crater Lake was only a summer job. Thus, I worked during the winters in Everglades National Park from 1992 to 2008. During the months of May and October, I traveled across the United States from Oregon to Florida to reach my seasonal jobs in these parks. These cross-country journeys allowed me to see so many iconic national parks multiple times.

One of the best perks as a park ranger was meeting friends who worked and lived in other national parks. It allowed me to stay with friends in their ranger houses for multiple days while I explored these parks. This saved me a lot of money. Even more, it allowed me to reconnect with friends who knew these places well and could easily recommend the best highlights in these parks. I stayed with friends in national parks such as Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Redwoods, Canyonlands, Death Valley, Capitol Reef, and Sequoia.

One national park alluded me on my cross-country road trips, Glacier National Park in Montana.

Glacier was always too far off my routes to reach it. Even more, the Going-to-the Sun Road that cuts through Glacier National Park was open for the year from mid June to early October. This road had a similar season for when it was open to vehicles as the Rim Road at Crater Lake National Park. Crater Lake’s Rim Road is typically open for vehicles from late June to sometime in October. Therefore, it would be too risky for me to take a very long drive for me in early May or mid-October up to northern Montana to try to see Glacier, only to be turned around with the Going-to-the-Sun Road closed for the season.

I never gave up on my dream to see Glacier National Park. I just never found a way to logistically make it happen as a seasonal park ranger.

Climate Change made me curious to see Glacier National Park

In 1998, I started giving ranger talks in Everglades National Park. Visitors then asked me about this global warming thing. Visitors hate when park rangers tell you, “I don’t know.” Visitors expect park rangers to know everything. Don’t you?

Soon afterwards, I rushed to the nearest Miami bookstore and to the park library to read all I the scientific books I could find on climate change.

The information I learned really scared me, specifically sea level rise along our mangrove coastline in Everglades National Park. Sea level rose 8 inches in the 20th century, four times more than it had risen in previous centuries for the past three thousand years. Because of climate change, sea level is now expected to rise at least three feet in Everglades National Park by the end of the 21st century. The sea would swallow up most of the park and nearby Miami since the highest point of the park road is three feet above sea level.

It shocked me that crocodiles, alligators, and Flamingos I enjoyed seeing in the Everglades could all lose this ideal coastal habitat because of sea level rinse enhanced by climate change.

I was so worried about climate change that I quit my winter job in the Everglades in 2008. I started spending my winters in my hometown of St. Louis Missouri to organize for climate action. Up until 2017, I still worked my summer job Crater Lake. I loved the incredible scenery there and wearing the ranger uniform with pride while engaging with park visitors.

In in the spring of 2008, I first mentioned to my superiors at Crater Lake that I wanted to give a ranger program about climate change. My Crater Lake supervisor, Eric Anderson, and the lead interpretive ranger, David Grimes, supported and encouraged my idea. I just did not feel like I knew enough or was brave enough to do such a program. Finally, in 2011, I felt I was ready. David helped me with the information and images about climate change that he had wrote about for years in the park newspaper. I used the PowerPoint graphs and information I received from the park scientists that they had shared with the ranger staff during seasonal training.

After months I of putting it together in my spare time, I debuted my climate change evening program at campground amphitheater on August 3, 2011.

My evening program title was The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly. I stole the title from the old Clint Eastwood 1966 spaghetti western film. With the subject of climate change, I talked about how the lake surface temperature has gone up in recent years due to climate change. However, the lake’s overall condition is “good.” Rising air temperatures from climate change have been “bad” for pikas, a mammal closely related to rabbits living at Crater Lake and in the western mountains. Finally, the “ugly” mountain pine beetles are destroying white bark pine trees at Crater Lake and other trees in the west. Historically, very cold winters kept those insects in check. However, rising temperatures from climate change allows more of them to survive the winter.

I blogged about my Crater Lake climate change evening program elsewhere. David Grimes videotaped the program on September 22, 2012, so I could upload it to YouTube. It’s not easy to travel to Crater Lake. Furthermore, I stopped working at Crater Lake in 2017. It is great to have this program on YouTube so that you can watch it.

Basically, from my 25 years working at Crater Lake National Park, I saw climate change firsthand. With my own eyes, I observed the annual average snowpack diminishing and the summer wildfire season becoming smokier and more intense.

At the beginning of my Crater Lake climate change evening program, I mentioned other national parks experiencing climate change. I gave the examples from Kenai Fjords National Park, with the loss of the Bear Glacier 1909 to 2005, Pederson Glacier 1909 to 2005, and the Northwestern Glacier from 1940 to 2005. I had contrasting photos of the glaciers receding starting from 1909 or 1940 (in the case of the Northwestern Glacier) and 2005. The Northwestern Glacier was especially troubling for me since both of my parents were born in 1940. It was stunning to see the disappearance of the Northwestern Glacier in 65 years.

At the other extreme, I shared that scientists are concerned we could lose all the Joshua Trees in Joshua Tree National Park over the next 50 years due to rising temperatures from climate change. I then talked how climate change would lead to sea level rise in the Everglades.

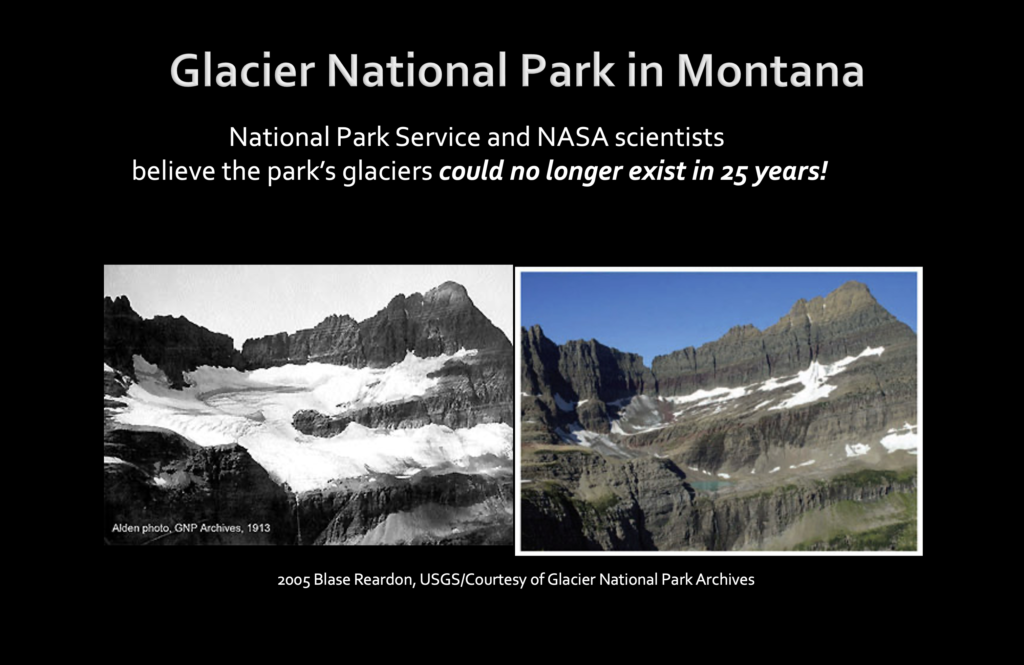

Among these national park examples, I showed the Shepard Glacier in Glacier National Park, Montana. I had a park photo of what that glacier looked like in 1913, compared another photo from around 2010. On top of that, I stated to the audience that the “National Park Service and NASA scientists believe the park’s glaciers could no longer exist in 25 years.”

In addition, I heard statistics from fellow park rangers and from the NPS that the glaciers in Glacier National Park might be totally gone by 2020.

Thus, from hearing this alarming news about the glaciers disappearing in Glacier National Park, I wanted to see this national park before the glaciers were totally gone.

I stopped working in the national parks after the summer of 2017 so I could organize full time for climate action. My wife and I moved to Portland, Oregon in February 2017. Glacier was too far of a drive from Portland. Before the pandemic, I was too busy with my climate organizing to travel to Glacier. During the 2020-21 COVID pandemic, it did not seem safe to travel to places like Glacier. In recent years, I was uncertain how I would ever see Glacier National Park.

A possible family road trip presents to see Glacier National Park

As I wrote previously, I met my wife Tanya after local businessman Larry Lazar and I co-founded the St. Louis Climate Reality Meet-Up group (now called Climate Meetup-St. Louis) in November 2011. I recall Tanya attending one of our first meetings in January 2012. I asked her out for coffee in February 2013. My pickup line was, “Maybe we could meet for coffee sometime and I could practice my climate change talk with you.”

The line worked! We started dating soon afterwards. As I joke in all my climate change talks: “If you join the climate movement, you might meet the person of your dreams.”

The audience always laughs and an older person in the audience typically responds with humor: “Sign me up!”

Tanya invited me to her parents’ house for dinner in April 2013 so they could meet me. Around that time, I dropped 7 Mentos into 2-liter bottles of diet Coke to make 25-foot fountains to demonstrate how volcanic eruptions work when I was a guest speaker for St. Louis area schools. Tanya has a quirky sense of humor like me. She thought I should bring the Mentos and Coke to demonstrate to her parents in their backyard after dinner. Her parents, Nancy and Rex Couture, didn’t say much. They seemed to enjoy the demonstration and they liked meeting me.

Tanya’s parents have always been very supportive of my climate organizing. They attended a climate presentation I gave that December at a county library in north St. Louis County. They came to see a couple of my Toastmasters speeches on climate change when I was an active member of South County Toastmasters. Even more, my mother-in-law, Nancy Couture, gave a heartwarming toast at our wedding reception on November 1, 2015. In the speech, she said,

“We admire you, Brian and welcome you in our family. The passion that drives you is admirable. You (are) working hard at making people understand the seriousness of climate change and we thank you for this.”

Tanya’s parents, Tanya, and I have always enjoyed our trips together. They typically come visit us for several days every August. We then take day trips to go hiking in nearby areas. Tanya and I visit St. Louis once or twice a year to see them and my parents. Nancy and Rex drive us to great day hikes in Missouri and nearby in Illinois. Nancy is originally from Denmark. All her siblings and cousins still live there. Tanya and I travel to Denmark every other year to see her relatives. We arrange to be there when her parents travel there to attend family events together. While we are there, we like to do some hiking and exploring local sites together.

In August 2022, the four of us enjoyed traveling on a road trip from Portland OR to the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state to see Olympic National Park. We had ideal warm clear summer weather to see the highlights of this splendid national park, such as the Hoh Rain Forest, the ocean beach at La Push, Cresent Lake, Marymere Falls, and a panoramic view of the Olympic Mountains at Hurricane Ridge. The last couple nights on this trip, we stayed with Nancy’s cousin Peter and his spouse Karen, in Sequim, WA. At Peter and Karen’s home, we ate outstanding sea food they caught nearby in Sequim Bay.

In addition, the four of us, plus one of Nancy’s older sister, Sonja and her spouse Erik, plus Nancy’s cousin Nils and his spouse Hanna, 8 people total, traveled to Yosemite National Park, California in May 2018. We had a terrific time hiking on the Mist Trail to see Nevada and Vernal Falls, driving to see Glacier Point, and a short walk to see the base of Yosemite Falls up close.

Nancy’s siblings and their spouses are getting up in years. Before the pandemic, it was a loose tradition that Nancy, Rex and Tanya visited Denmark every other year. In the year in between, Nancy’s siblings, their spouses, and some cousins came to the U.S. to explore areas, such as Missouri and Arkansas, the Pacific Northwest, Washington D.C. and Philadelphia.

During our June 2022 trip to Denmark, Nancy asked her siblings if they would be open to traveling in the U.S. in 2023. She thought that they would probably not be interested. Surprisingly, they expressed an interest to see America again. They reached a quick consensus to do a big family road trip to see Glacier National Park in 2023. Tanya enjoyed these big family trips. Thus, it looked like this would be my big opportunity to finally see Glacier National Park.

Traveling from Seattle, WA to Glacier National Park, MT in September 2023

Tanya’s parents, Nancy and Rex Couture, made all the arrangements for this 10-day trip. Their plan was to meet in Seattle, WA and travel to Glacier National Park, MT from September 5th to September 15th. She called me to help her book one of the hotel reservations, such there was a limit of how many rooms at one hotel could be booked under one name. In addition, she asked me contact Glacier National Park to see if I could book one of the days for their vehicle reservation system. Like her, I did not have success booking a vehicle reservation for one of the days. I knew nothing about Glacier National Park, so I left all the planning for the trip up to them.

On September 5th, Tanya and I took the Amtrak Cascades train to the Seattle area to meet up with the group. It was a pleasant 3-hour train ride. We got off the train at the Tukwila train station, not far from SeaTac International Airport. Tanya and I figured that getting off at Tukwila would put us closer to SeaTac than the downtown train station. All of the participants on this trip were flying into SeaTac and picking up their rental cars around that area.

Tanya and I stepped off the train at the Tukwila station at 11:30 am. When we arrived, we saw no restrooms, no Amtrak staff, or other services as we waited for several hours for one of Nancy’s cousins to pick us up by car. This commuter parking lot and station, also used by the local Seattle Sound Transit light rail, was a mile walk to the nearest gas station to use the bathroom. Tanya and I ate our lunch in the shade on the commuter lot benches and read our books. I periodically ran up to the train platform to see the freight and passenger trains roll past the station.

Finally, Nancy’s cousin, Jørgen and his wife Marianne picked us up after 3 pm. The plan was to retrieve Tanya and me after 1 pm, but it took a lot longer at the rental place to obtain their car. We then met up with all 14 people at the scenic Snoqualmie Falls, located about 45 minutes east of Tukwila and SeaTac Airport. Tanya and I saw Snoqualmie Falls on June 30, 2018. However, it rained hard that summer day, making it awkward to stay warm and dry while trying to enjoy the waterfall. After eating an early dinner at the Snoqualmie Lodge, the 14 of us went by our three vehicles to drive an hour and a half east to spend the night in Ellensburg, WA.

From that point forward, three vehicles (a large minivan, a Chevy Tahoe SUV, and a jeep) transported 14 of us towards Glacier National Park over the next three days. We stopped many times over the next three days for sightseeing. Our first stop was Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park for a view of the Columbia River and Native American petroglyphs. These petrographs are some of the best examples of petroglyphic art in Central Washington. They were removed from their original site, below which is now covered by the Wanapum Reservoir.

From there, we drove along Lenore Lake and Banks Lake on Hwy 17. We stopped at the Dry Falls overlook for a picnic lunch. After lunch, we headed up to Grand Coulee Dam to take a guided tour of the reservoir. The dam is one of the largest concrete structures in the world and the largest hydro-electric producer in the United States. We spent the night in nearby Grand Coulee, watching a laser light show projected on the dam that evening.

The next morning, we watched a 45-minute film at the Grand Coulee Dam Visitor about the construction of the dam. Tanya and I felt a bit restless that we wanted to move on to see other sites along the route to Glacier National Park. I worked at Crater Lake National Park as a seasonal ranger for 25 years. Crater Lake’s Park film only takes 17 minutes to explain the Mazama volcano, the climatic eruption, and the collapse of volcano that created Crater Lake. Tanya and I thought, ‘Why would it take 45 minutes to explain the construction of a dam?’

Others in our party wanted to see the film. Tanya and I were stuck at the visitor center since we did not drive our own vehicle. Thus, we watched the film. The film surprised us that it was good. It showed a different time when the U.S. built huge civil projects to improve the way of life for business, farmers, and provide electricity for citizens. It sparked good conversations in the vehicles afterwards why doesn’t the U.S. build massive projects like that anymore.

From Grand Coulee, we drove to take a short hike at Hawk Creek Falls State Park and had a picnic lunch on a tranquil spot near Fort Spokane along the Spokane River. That evening we made it to Bonner’s Ferry, Idaho, way up north in the Idaho panhandle. Bonner’s Ferry is less than 30 miles from the Canadian border. I was excited because the next day we were scheduled to travel to Glacier National Park, Montana. Since working at Crater Lake National Park in 1992, I wanted to see Glacier for over 31 years. We were now only about 180 miles or a 4-hour drive away from Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park. My in-law’s itinerary had us eating dinner there the next day. My dream to see Glacier was coming true the next day. Or so I thought…

My disappointment of not making it to Glacier National Park on Friday, September 8th.

We woke up on Friday morning to have a continental breakfast in the lobby of the hotel. The food available was some toast, cereal, and some fruit. It was minimal for a breakfast, but I was fine with it. I was eager to see Glacier and whatever sights we would see along the way.

Basically, everyone in our group was ready to leave the motel in Bonners Ferry around 9 am. The first item on the agenda was the Boundary County Historical Society Museum in downtown Bonners Ferry. However, the museum did not open until 10 am. Therefore, we had time to kill.

The owner at the hotel at Bonners Ferry recommended that we visit the Kootenai National Wildlife Refuge, located near the city center, while we waited for the museum to open. We went to the Wildlife Refuge took some pictures of the Kootenai River as it meandered and made a sharp curve by the boat dock. We saw a Bald Eagle in a close by in a tree next to the road. However, we saw no other animals as we drove the loop road through the refuge. One member of our party was accidentally left behind at the boat dock as we made the loop drive through the refuge. He was fuming as we returned to pick him up. It was a bit chaotic and not much to see at this refuge. It served the purpose to kill time, but that was all.

In my mind I thought: Can’t we just drive towards Glacier? Why all these distracting side trips?

The Boundary County Historical Society Museum in downtown Bonners Ferry was mildly interesting when we walked inside at 10 am. I enjoyed chatting with the official volunteer greeter of the museum. His name was Howard. He was a lifelong resident of Bonners Ferry in his late 70s or early 80s. Howard sat in a chair and recounted Bonners Ferry stories for anyone who was interested. I was anxious to see Glacier, but the others seemed content walking around the crowded contents of the museum. I made the best of it by having an engaging conversation with Howard and I liked hearing his lifelong account of living in Bonners Ferry. At the same time, I was eager to see Montana and Glacier National Park, the goal of this trip.

It was around noon that we left Bonners Ferry. We did not cross the Montana boundary until around 12:30 pm. At 1 pm, we stopped at the Kootenai Falls Park right along Hwy 2, which was 22 miles east of the Idaho border. We had a picnic lunch there. Afterwards, our more agile group members hiked over a mile to the Kootenai waterfalls and then another mile along the Kootenai River to the “swinging bridge” that spanned the river. The main falls dropped over 30 feet with a series of loud roaring rapids around it that looked too dangerous to kayak or try on river rafting. The river, the falls, and swinging bridge was nestled against a steep ridge of a mountain covered in pine trees that felt like we officially arrived in western Montana. It got me more excited for what we might see that day in Glacier National Park.

After the able-bodied hikers in our group, such as Tanya and I, returned to the parking lot, the Danish relatives gathered at a picnic table having a coffee break and eating ice cream. I was not interested in food or any drinks since we ate lunch less than two hours ago, but I was hungry to see Glacier National Park. We left the Kootenai Falls Park sometime after 3 pm.

We had a two-and-a-half-hour drive to Columbia Falls, Montana to the house we rented for the next three nights. We arrived after 5:30 pm. The original plan was to unload our luggage and then drive to Lake McDonald Lodge inside Glacier National Park for dinner.

We arrived in Columbia Falls to a bright blue sky with no clouds or haze. The weather was in the lower 70s. It was the perfect weather to visit a national park on a late afternoon. The sun was lower in the sky which would make for perfect photos. The park boundary was only about 19 miles away, about a 30-minute drive. It was so close I could almost taste it. I was pumped full of energy to see Glacier National Park. I was within minutes of reaching a life goal.

Then I received the bad news. Almost everyone in our party were tired and did not want to go to the park. My wife Tanya was interested, as well as my father-in-law Rex, but that was it. Everyone else felt worn out from being a car passenger or driving that day. I was livid. I wanted to scream at someone, but I knew it would not do any good.

Instead, I immediately went for a long walk to “cool my jets” and with all the adrenaline I felt in the moment. We stayed at a large house at the back end of the Meadow Lake Resort. I decided to take a long way around the resort area. I regretted I did not drive my own car on the trip to take off at that moment to explore the park on my own with possibly my wife Tanya and my father-in-law Rex. I visited many national parks on my own, so I felt trapped on this trip. I was at the mercy of the group with the coffee breaks, side excursions, slower members taking longer to get ready, and long conversations about how to meet at the next rendezvous point.

Yes, we would travel to Glacier National Park the next day. However, we would never have that chance again to visit Lake McDonald and have dinner at the scenic lodge that Friday afternoon when the weather was perfect. The park enticed me to visit, but I had no means to get there.

My wife texted me that they were walking to the Meadow Lake Bar and Grille for dinner, which happened to be a few minutes away from the spot I just walked past. I turned around to walk to the Bar and Grille. I waited for my wife and the rest of the group to arrive.

The long walk did help exhale those feelings of anger, disappointment, and hurt. By the time Tanya and others met me at the restaurant, I put on a happy face and resigned myself to the situation. I would see Glacier National Park, but it would not happen until the next day.

Finally seeing Glacier National Park for the first time on Saturday, September 9th

The day finally arrived for our group and me to see Glacier National Park. To my ongoing ire, we got off to a slow start that morning. We bought gas, which always took time to figure out the gas pumps at each location. We then ran into a long line of vehicles proceeding to the entrance station. Fortunately, the traffic moved somewhat quickly through the park entrance. It was a relief that it moved much faster than when Tanya and I visited Mt. Rainier National Park in July.

Minutes after we entered the west entrance of Glacier National Park, we stopped at the Apgar Visitor Center. I was on a sole mission to get a tri-fold park map. I asked inside the visitor center store, but they directed me to a box outside that had maps. The box was empty. I then wanted to ask a ranger, but there was a long line to ask the ranger questions. Three different rangers were behind outdoor desks to answer visitor questions. However, the visitors were very longwinded asking the rangers to plan their trips and to go over the junior ranger badges with the kids. Our group was leaving the visitor center to head back to our vehicles. I gave up my place in line to catch up with them. Thus, I could not get a map. My day was not off to a good start.

On the bright side, we had fabulous weather that day, as we did throughout our trip. The weather was sunny and partly cloudy. It felt like a perfect day to go hiking and explore a national park. There was a hint of an autumn breeze in the air to prevent the day from feeling too hot.

A long stretch of the Going-to-the-Sun Road by Lake McDonald for several miles was stripped of pavement and in the process of getting repaved. We were lucky no road crew worked on this Saturday morning to delay traffic and impede our time to travel through the park.

All of us in our group had our jaws open with the beauty of the Going-to-the-Sun Road. I worked 25 years at Crater Lake National Park, traveled to Yosemite several times, driven through Yellowstone more than once, drove along the south rim road at the Grand Canyon, etc. Nothing prepared me for the magnificent landscape as we climbed in elevation towards Logan Pass. The jagged mountains and deep forested valleys of Glacier National Park were mesmerizing.

We had a picnic lunch at the Wild Goose picnic area. Tanya and I, and the more physically able in our group, hiked 2.4 miles one way to St. Mary Falls. We walked on the trail along St. Mary Lake with the towering rocky peaks of Glacier National Park dominating all around us.

As we hiked that day, something seemed odd. I noticed the same thing the next day when we were at another area of the park, Many Glacier. None of the mountain peaks had any snow or glaciers on them. It felt eerie. Yes, all these mountains probably get a good snowpack for the winter that melts by mid to late summer. From my 25 years working at Crater Lake National Park and visiting other national parks, I understood seasonal winter snowpack is gone by late summer. At the same time, this was Glacier National Park. Shouldn’t there have been some sight of a glacier somewhere?

A sign on the Going-to-the-Sun Road near the high point of the road points to Jackson Glacier on a distant mountain, but I found it hard to see. As I spent more time in the park, it felt like we were at an excellent party where the host disappeared long ago. The party was fantastic. I would go to this party again. However, it seemed like it was nearly impossible to get a glimpse of the guest of honor.

We had one more day to visit Glacier National Park on Sunday, September 10th. I was determined to ask a park ranger or a park employee to find out what’s happening with the glaciers.

Visiting Many Glacier area in Glacier National Park on Sunday, September 10th

I must give Tanya’s parents, Nancy and Rex Couture, full credit for planning an excellent itinerary for every day of our trip from Seattle, Washington to Glacier National Park, Montana, and back September 5-15. Sometimes we did not make our marks for places to visit because arranging 14 people to travel together is like herding cats.

Sunday, September 10th was one of the best planned days of the trip. We left the house we where we stayed around 9 am. We arrived at the West Entrance Station for Glacier National Park around 9:30 am. This time, we were stopped for road construction around the Lake McDonald area. With winter coming soon to the mountains, I figured the road construction crew would be under pressed to complete their road re-pavement work soon. The good news was that it was only about a 5-to-10-minute wait.

It was an ideal beautiful day to visit Glacier with just a few clouds and a bright blue sky. The plan was to drive across the park on the Going-to-the-Sun Road and then travel to the northeast area of the park to known as Many Glacier. From Many Glacier, we would have a picnic lunch, travel on two different boats, and then allow folks in our group the option to do some hiking.

On the way to Many Glacier, we stopped at the Lunch Creek pullout on the Going-to-the-Sun Road. This pullout is just past Logan Pass, the highest point on the road and the spot where the Continental Divide crosses the road. The view of the mountains, the cascading creek, and the pine trees was magnificent at Lunch Creek.

My father-in-law, Rex Couture, wanted to look for a specific rock there, called stromatolites. These rocks are the fossilized remains of algae dating back a billion and a half years ago. At that time, Glacier National Park looked more like the modern-day Bahamas, with clear waters holding some of the most primitive life forms on earth—cyanobacteria (blue-green algae)—which these rocks preserve in great abundance. Rex could not locate those rocks, but it did not matter. It was very sublime to taken in the scenery at Lunch Creek before we had to drive further.

From there, we drove to Many Glacier without stopping. Correction: we stopped once so I could take a picture of the Glacier National Park entrance sign at the east entrance on the Going-to-the-Sun Road. When we arrived at Many Glacier, the panoramic view blew us away with the pointy jagged peaks and an emerald dark green reflective lake in front of the mountains. In the foreground was the Many Glacier Hotel. The Great Northern Railway built this hotel in 1914-15 as a Swiss-style lodge. The Many Glacier area is known as the “Switzerland of North America.′′ I have never been to Switzerland to compare it to Many Glacier. However, I could have spent hours staring at the scenery there from the back porch of the Many Glacier Hotel.

The Boat Tours to see Grinnell Lake in Glacier National Park

My in-laws, Nancy and Rex Couture, arranged for all 14 of us to take a boat tour that departed from behind the Many Glacier Lodge on Swiftcurrent Lake. A month before the trip, Nancy emailed the itinerary to all the trip participants. Her description for Sunday, September 10th:

“We have a boat tour scheduled for 2 pm. This is a guided tour. We need to plan on being at Many Glacier 1 hour prior to tour. We will sail one lake then traverse up a relatively steep hill to the next lake. The incline is described as a 5 story climb. Should this be too much for some,

the boat will return to Many Glacier and hikes can be taken there.”

For 20 years of working in the national parks, I narrated boats in the Everglades and Crater Lake National Parks. It felt weird for me to take a boat tour in a national park without narrating the tour. The boat was different than any of the tours I led in the Everglades or Crater Lake. It had an enclosed wooden top and glass windows. Tanya and I sat in the very back away from the others in our group. I wanted the flexibility in the back to take more photos and a chance to be away from the others to enjoy each other’s company during the tour.

Sadly, sitting in the back of the boat, we were right next to the noise of the gruff humming engines. This made it hard to hear the tour. This was my pet peeve giving boat tours in national parks. Why don’t they design the boats to be quieter so visitors can hear the tour narrations?

The boat captain narrated the tour. I never piloted a boat at Crater Lake, with the rare exception of one emergency at Crater Lake. The battery died on the boat and the engine would not start. However, we put the passengers in PFDs to be safe, we got towed back to the dock on the National Park Service research boat. The boat captain secured and monitored the boat lines tied to the research while I boat steered the boat while it was getting towed.

That always seemed like too much mental work for me to be operating a boat while giving a tour narration. Our boat captain was Nicole. I was pleased with the narration that I could pick out over the loud boat engines. Like it or not, some visitors want park employees to have some humor in their tour narrations. Other visitors just want the facts without any corny jokes. With that said, I thought that Nicole nailed the one joke I could hear over the boat engines.

She talked about the Many Glacier Hotel how mountain goats occasionally and accidentally cause damage to the hotel roof during the winter. To monitor the lodge during the winter, she said there was one individual on site all winter. She then dryly remarked, “You might have seen a documentary about this on Neflix. It’s called The Shining.”

I laughed as well as several of the boat passengers. I thought she nailed that joke.

We then reached the other end of Swiftcurrent Lake. Three of the oldest members of our party stayed on board the boat to return to Many Glacier Hotel. They sat in the Hotel’s Great Hall to have cocktails and read while they waited for the rest of us to complete our hikes and return.

The other 11 members of our group walked up the hill, which seemed more like a two- or three-story building to take the other boat tour on Lake Josephine. The boat then let us off on the far side of Lake Josephine for an optional hike 3.5 mile hike to see the Grinnell Glacier up close, a 1.1 mile hike to see Grinnell Lake, or ride the boats back to Many Glacier Hotel. Captain Nicole announced she would lead a guided walk to Grinnell Lake.

Tanya and I decided to hike on our own to Grinnell Lake. The late afternoon sun angling to the west made it hard for us to see the Grinnell Glacier high up on Grinnell Peak as we looked towards the west. I could barely make it out with the dark shadows that the wide shoulders of the mountain refusing to let us get a good look that time of day. From what I could see, it looked like the glacier was hanging on by its fingernails, doomed to disappear soon.

Tanya and I enjoyed the hike out to Grinnell Lake. It was nearly a flat trail through the woods as it headed towards the lake. The lake had a mint green hue from the glacial silt in the water. It was captivating color that I had not seen in a lake before, even glacial lakes that I might have encountered previously. Tanya and I enjoyed taking lots of photos and appreciating the view of the lake with the silhouette of the towering Mount Grinnell directly behind the lake.

Talking to Captain Nicole about the glaciers receding in Glacier National Park

On return hike, we ran into Captain Nicole. She finished her guided walk to Grinnell Lake and spent this time casually chatting with visitors. We talked for close to 15 minutes. As we got off the second boat at Lake Josephine, I asked her a quick question about the glaciers and mentioned that I used to be a national park ranger. She was curious to hear about my story.

I told her that I worked 25 years at Crater Lake and the Everglades as a seasonal interpretive park ranger giving public talks, such as boat tours. I shared how I discovered climate change over 20 years ago working the in Everglades. Even more, I saw the diminishing annual snowpack and a more intense wildfire season working 25 years at Crater Lake National Park. Seeing climate change in the national parks caused me to spend my winters organizing for climate action in my hometown of St. Louis. This was how I met my wife, Tanya, who was standing next to me.

I then elaborated that I started giving evening ranger campfire programs about climate change at Crater Lake over 12 years ago. I began that program by talking about how climate change impacted other national parks, such as Glacier. I gave the example of the Shepard Glacier in this park. In that presentation PowerPoint, I showed a park photo of what that glacier looked like in 1913, compared another photo from around 2005. I relayed my understanding from over 10 years ago that all the glaciers in Glacier National Park might be gone by 2020.

I asked Captain Nicole if she heard that same fact. She affirmed that she had. Nicole said that she was originally from Minnesota and she is 25 years old. She first visited Glacier National Park when she was 9 years old, which would be around 2009. She remembers hearing that fact then and she recalls seeing a difference in the glaciers in the park from 14 years ago until now.

Nicole stated she is very worried about climate change. She likes to share information about climate change at Glacier National Park during her boat tour narrations. However, she struggles internally how much knowledge to share since with park visitors since they are on vacation. She is uncertain the amount of climate change facts to give visitors if they would be truly open to listening to the information.

I had that same dilemma when I wanted to talk about climate change in the national parks over 12 years ago. Some audiences were very receptive, other audiences just wanted to be entertained since they were just on vacation. I then asked her the key question: how many glaciers are left in Glacier National Park?

She responded the park currently has 25 glaciers. She defined a glacier as a mass of ice so big that it flows under its own weight and has a size about 25 acres. She then noted that around 1850, an estimated 150 glaciers existed within the present boundaries of the park.

Even though I knew for over a dozen years that the glaciers were disappearing in Glacier National Park, it was still sobering and sad for me to hear this from a Glacier Park employee. I shared with Nicole my analogy that my visit to Glacier felt like we were at an excellent party where the host disappeared long ago. She had no pushback or objections to my observation.

Nicole announced on the boat tour that it was her final tour of the season. I wished her success in whatever she did next. Nicole informed Tanya and me that she did not know what she was doing for the winter. I understood that feeling 100%. Many seasons when I left my summer job at Crater Lake National Park, I did not know what I was doing for the winter.

Nicole told us that she had an excellent summer. She loved working there, even more than the previous summers. The snow from wildfires was not bad, except for the beginning of June with the Canadian wildfire smoke than impacted much of the eastern U.S. Nicole liked her roommates, but she could almost hear them recite each other’s boat narrations in their sleep. She hoped to return to Glacier next year.

I gave Nicole my business card just in case she wanted to learn more about my climate change comedy. I felt old chatting with her since I was around her age when I started working at Crater Lake in 1992. I turned 24 years old that July. Many of my co-workers at the Crater Lake gift store in 1992 were around my age if not a year or two younger. I am now old enough to be Nicole’s dad and old enough to be a parent of the new generation now working in the national parks.

My conversation with Nicole felt like the future is in good hands, especially with the next generation of park employees. She loved Glacier, enjoyed interacting with the park visitors, cared to share accurate information about the park, and was deeply concerned about climate change. I apologized for taking up to 15 minutes of her time. However, she indicated that I was not interfering with her work, and she liked her conversation with Tanya and me.

Leaving Glacier National Park to see Mt. Shuksan at North Cascades National Park

We hiked all the way back from Grinnell Lake to Many Glacier Hotel. It was a 3.5-mile hike with not much elevation rise or fall. The hike skipped taking the boat tours back. The trails skirted along Lake Josephine and Swiftcurrent Lake. The scenery was astonishing as we stopped frequently to take pictures. Our goal was to pace our walk to return about the same time that Tanya’s parents and others in the group returned to the Many Glacier Hotel riding on the boats. We achieved success that we showed up the same time their boat arrived. Tanya and I were delighted with all the exercise we received that day hiking on the trails.

I felt a bit of sadness that our 10-day trip to Glacier National Park had reached its climax. We were now getting ready to leave the park for the two-hour drive to return to the house we rented Columbia Falls, Montana. The next day, Monday, September 11th, we dropped two members of our group at the Kalispell City Airport. We then had 12 people to travel the next couple of days to North Cascades National Park, Washington.

On Wednesday, September 13th, we reached the Mt. Baker Ski Area at 6 pm to see Mt. Shuksan. The low afternoon western sunset lit up the mountain brilliantly as we saw it. We spent the night at a large house in Glacier, Washington, about a 40-minute drive from the Mt. Baker Ski Area. We then returned to the Mt. Baker Ski Area the next day to drive to the of the road at Artist’s Point. From that location, we had fantastic views of Mt. Baker and Mt. Shuksan.

I had a poster of Mt. Shuksan on my wall in high school in St. Louis in the 1980s. I had no idea where that mountain on my poster was located. However, I vowed to see that mountain someday. When working in the national parks, I learned Mt. Shuksan is in North Cascades National Park. At the end of May 2009, I took advantage of a two-week vacation break from my Crater Lake job to go see Mt. Shuksan. With the spring snowpack and timeless glaciers clinging to the mountain, I thought it was the most beautiful site I saw in my life. I still think that to this day.

The Mt. Baker Ski Area with the view of Mt. Shuksan is my favorite spot on planet Earth. It is, as they saw these days, ‘My happy place.’ Ironically, the glaciers on Mt. Shuksan are very easy to spot, compared to the glaciers at Glacier National Park. It must be noted that Mt. Shuksan is roughly 50 miles from the ocean waters next to Bellingham, Washington. Mt. Shuksan is a lot closer to the Pacific Ocean than the mountains of Glacier National Park. Therefore, Shuskan gets a lot more snow and potential for glaciers than the mountains of Glacier National Park.

I shudder to think how Mt. Shuksan’s glaciers shrunk due to climate change. There’s documented evidence the snowpack and glaciers have receded on Mt. Baker in recent years.

Final Thoughts

I know from my own life of working at Crater Lake and Everglades National Parks that climate change is real, human caused, scientists agree, and is negatively impacting our national parks. Even more, I know from reading books and published articles from climate scientists and clean energy experts that we can limit the damage caused by climate change if we chose.

I had the good fortune in my life to work 25 years in the national parks, travel to many of the most iconic American national parks, marry Tanya who likes to hike in natural areas, and marry into a family that likes to visit national parks and scenic areas. Spending time in national parks and nature allowed me to become the climate advocate that I am today.

Because it is a remote and difficult location to travel, I am uncertain if I will see Glacier National Park again in my life. My conversation with Captain Nicole at Glacier National Park reminded me that I am getting older. I am now 55 years old and probably have more yesterdays than tomorrows. Thus, a future opportunity to go to Glacier might be unlikely. I wish Tanya and I lived closer to Glacier to enjoy it more frequently.

I do know for sure that my recent trip to Glacier National Park, my ample visits to see Mt. Shuksan at the Mt. Baker Ski Area, and working 25 years at Crater Lake and Everglades National Parks have inspired me to commit my life to take action for climate change.

From my time working in the national parks and hiking in the outdoors, I believe that we have an innate sense of needing nature and to connect with grand scenic beauty.

More than 100 years ago, American naturalist John Muir wrote in his book The Yosemite, “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul alike.”

More recently, the late Harvard naturalist Dr. Edward O. Wilson coined the term Biophilia, which he described in his book by the same title, as “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life.” We hope when we spend time in nature to see a large mammal, colorful bird, fascinating reptile or incest, or a majestic forest of trees. Even if we don’t see any wild animals in the outdoors, we still have deep longings to connect to the natural world. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines biophilia as “a desire or tendency to commune with nature.”

Most of us have an internal longing to spend time in nature, love it, protect it, and to find a way to reduce the harm caused by humans. Yes, I acknowledge that some people are solely interested in power, greed, corruption, domination, and pleasure. However, most of us do want to connect with nature. Many of us dream of traveling to remote and iconic places, where we can be in nature and learn about it. Some of us even crave that sense of renewal, peace, and healing from spending time in the outdoors.

Spending time in nature should challenge us to take better care of it. To love and appreciate the natural world should inspire you to want to protect and defend it from imminent threats such as climate change. One should leave nature with a sense of purpose to protect it. I don’t think one should leave nature as the same person who entered it. One should leave nature with a sense of elevated renewal. The gift of communing in the outdoors should inspire us take better care of ourselves, be more caring to others, and be better stewards or citizens of our planet.

This was why I stopped working as a national park ranger in 2017. I loved the national parks and nature. I felt most at home there. At the same time, I learned and saw first hand that nature and our national parks are suffering because of human caused climate change. That awareness called me to be a climate change advocate. My time working in the national parks changed me to become the person writing this today.

My recent visit to Glacier National Park reminded me that I have a lot more work to do in my climate advocacy. My own eyes saw lack of glaciers there. My conversation with Captain Nicole confirmed that the glaciers are disappearing. Recently I read on the Glacier National Park website that ‘the retreat of glaciers seen in recent decades can be increasingly attributed to human-caused climate change.’ With this new insight, Glacier National Park is now challenging me to be a better and more effective climate change organizer.

American writer and environmentalist Edward Abbey wrote in his 1977 book The Journey Home,

“The idea of wilderness needs no defense. It only needs more defenders.”

I went to Glacier eager to complete a life goal to see it, and spend quality time with my wife and her extended family. I left Glacier with a new determination to take climate action.

Thank you, Nancy and Rex Couture, for this fantastic opportunity to see Glacier National Park!